Philip Hensher: Shakespeare, salaries – and why inequality is not inevitable

How much does your neighbour earn?

Do you think he deserves it? What do you think he thinks about your earnings? Should he be made to earn less, or should you be made to earn more? When the lion lies down with the lamb, and the stockbroker with the shop assistant, what, exactly, will that achieve?

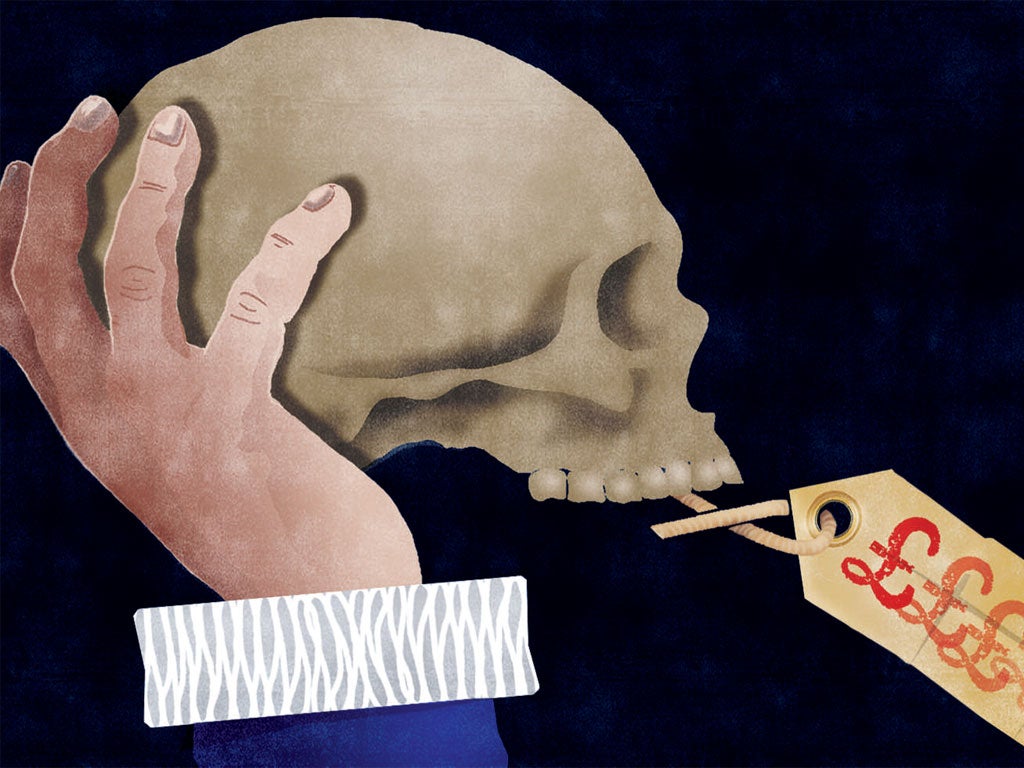

Outrage has been expressed at the news that Britain's top executives saw their salaries rise by 3 per cent last year. If that doesn't sound like much, they also saw their average bonus rise by 23 per cent on 2010. If that weren't enough, calculations have shown that additional long-term incentive plan values make up the rise to an overall 49 per cent.

It's pretty hard to justify such rises in the current financial and business climate. But what is to be done about it? The GMB union called them "elite greedy pigs". Other union leaders said that institutional shareholders should exercise more restraint, or that worker representatives on company boards should work towards narrowing the gap between boardroom and shop-floor wages.

I've tried extremely hard, but I find it almost impossible to give a toss about inequality per se. That's not the same as not caring about the poor. The people at the bottom of economic life in a civilised society should not struggle for existence, shelter and food. I also think that inequality should not be an insurmountable obstacle, transmitted from generation to generation. But inequality as such – the idea that one person is very much richer than another through the inequality of their own labours and responsibilities in life? Nope. Couldn't give a toss about that one.

On Thursday, this paper printed a list of Britain's 10 top-earning chief executives, with earnings of between £18.4m (Mick Davis of Xstra) and £8m (Dame Marjorie Scardino of Pearson). To my slight surprise, I saw that one of the names on the list was someone I sat next to at a very jolly lunch last week in London. His income, really, is no more my business than mine is his. His shareholders can certainly take an interest: if the business is run efficiently, then they will take a firm view on whether he is worth it. Why on earth should I be expected to care that my neighbour at lunch had an income of 60 or 70 times mine last year?

Desperate poverty has no place in our society. But how will reducing chief executives' pay help with that? Let's do the maths. Sir Terry Leahy, the ex-chief executive of Tesco, got £12m in his last year. Let's reduce him to, say £500,000, and give Tesco's 260,000 UK employees an extra £3.68 a month. Is that really going to be much more help than exploiting and rewarding the business acumen that took Tesco to record worldwide profits?

Complaints about the earnings of the very rich miss the point. Obviously, it is a scandal that anyone in the public sector is paid more than the Prime Minister – vice-chancellors, managers of hospitals. But there is no real harm in very powerful people in the private sector being paid very large sums of money, with two provisos. First, they should deserve it in the eyes of their shareholders, and be forced to justify it every year. Secondly, the private fortune should be a shining beacon of social mobility. Much better that people dream about the £20m pay packet than the £100m lottery win.

We've allowed our concerns about inequality of income to swamp concerns about what truly matters: inequality of opportunity. The Bertelsmann Foundation in Berlin this week published a report which classed Britain 15th out of 31 nations for social justice. It lumps together, however, some very different factors, including inequality of income along with inequality of education. We should be extremely worried that 75 per cent of those children from the richest fifth of society get five good GCSEs or more, whereas only 21 per cent of those from the poorest fifth do.

Should we be worried that some individuals were thought worthy of earning tens of millions of pounds, and many were not? Should we not be more worried that someone coming from that poorest fifth, like Sir Terry Leahy, would now be rather venally inspired by the thoughts of a £20m pay packet and painfully find that that opportunity was nowadays available only to the privately educated children of the rich?

Just how much we have lost faith in the idea of the equality of talents and the ideal of the equality of opportunity is shown by an extraordinary phenomenon which might not be thought to have much to do with anything. It's the revival of the Earl of Oxford theory of Shakespeare's authorship, now being proposed by a ludicrous film, Anonymous, and a surprising number of professionals. The theory runs that the actor Shakespeare could not have written the plays ascribed to him: they must have been written by a well-educated nobleman, familiar with Italy and the learned classics.

Of course, it's total balls. The author of Shakespeare clearly didn't know Italy at all, was a keen but patchy reader, and the Earl of Oxford died in 1604 anyway. The age could produce a much more learned author in Ben Jonson, the stepson of a bricklayer. But why do we, quite suddenly, think there's something in this crap?

It's because we ourselves have got used to the idea that inequality of opportunity, as well as status, is an inevitable thing. Ability, opportunity, learning and skill are not just unequal, but linked in our minds to how much money we have. Of course we start to think that only a posh bloke could have written Shakespeare, when we accept that children with money are naturally going to do better at school. The only way a Shakespeare could be acclaimed as a genius is the sort of random fluke the film depicts. Complaining about munificently rewarded CEOs is entirely pointless. What would be more fruitful would be to wonder about the number of state-educated CEOs of the FTSE 100 companies, or the number of women, or British-born ethnic minorities.

What those figures are like is what matters, and will still matter in 30 years, not what they earn.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments