Rose Prince: And what first drew you to the turkey millions, Mr White?

Can Marco, Gordon and Jamie retain culinary integrity when they play shop

Twenty years ago, I watched Marco Pierre White roast a chicken for Sunday lunch. He was then at the height of his powers; a notorious yet respected chef, on his way to winning his third Michelin star. Deftly carving the wings, he explained that it was a poulet de Bresse, a pampered, black-legged hen from France that had lived to a ripe age, foraging freely in meadows, and was likely stroked to death.

Not like a Bernard Matthews turkey, eh? For this is the poultry that White will now promote. Matthews has faced more than one allegation of cruelty to the birds on his farm. But aside from the animal welfare concerns, pappy, industrially reared turkey is not premium food. It would get nul points from a Michelin inspector. But White seems no longer to care what Michelin thinks. Before the Bernard Matthews deal, he endorsed a range of soups for the Morrisons supermarket chain, and Knorr Touch of Taste chicken stock. He now recommends putting Knorr into moules marinières.

This is not snobbery on my part, but sadness. White was a god of good food. Young chefs still look up to the work he did in the late Eighties. He taught me a lot about cooking as well as ingredients. One evening watching him and his chefs at work in the kitchen at Harveys in Wandsworth, I remember a young, eager blond chef coming in to help. We called him Gordon.

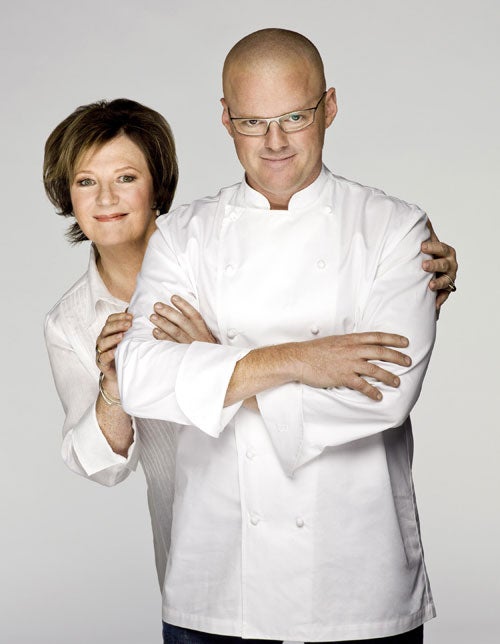

Gordon Ramsay, the son of a violent alcoholic, now promotes Gordon's gin. Jean-Christophe Novelli is the face of Findus. Delia Smith and Heston Blumenthal, self-styled respectively as the "queen of cooking" and "best chef in the world", are to sell Waitrose. Gary Rhodes used to give his blessing to Silver Spoon sugar. Jamie Oliver has earned millions as the face of one of the all-powerful, big four supermarket chains, Sainsbury's.

Like the ex-Blairite ministers rumbled last week, most celebrity chefs are for hire. Not all endorse the food industry, but for most it is inevitable that they will, one day, take money to endorse a brand. Is it greed? I do not think it is that simple. Why the chef sells out is part of a progression that begins with television and its incredible power.

The embryonic celebrity cook is not well paid by the broadcaster. The visibility pays, however, and, if the camera likes the chef and the ratings are healthy, the tie-in book of the series should sell plenty of copies. Already the chef will have an agent, hot on the case, looking for deals. Soon there will be discreet endorsements and partnerships. A range of kitchenware, some paid appearances at the right sort of event, a restaurant chain .... A star is born.

The first million has been banked. The chef is happy, he is loved. His Christmas show caused a run on kumquats that has reduced the national debt of the producing country. He gets a third series from the BBC. Then bigger business comes knocking, wanting to collaborate on a range of after-dinner chocolates. Another company launches his range of ready-made pasta sauces. The chef is busy now, and cannot always keep his eye on all the pies he's put his fingers into. The chocolates were OK, but a bit mass market. The sauce factory is adding too much salt.

Now married, the birth of the first child is in the tabloids. He has bought a big family house in London (there's a Hollywood actress and a rock star up the road). He is so popular that nothing can stop the upward mobility. Or could it? Like footballers, like all performers, a celebrity chef has no idea how long his career will last.

When the supermarket chain/sugar giant/intensive meat company makes its approach, he is contemplating the future: the mortgage, the business expansion, school fees for three children and there's a rumour the BBC has found a new star. This time, however, the deal on the table is not a range of chocolates, but his smiling face on their billboards and packaging. Its products are not the kind he would normally cook with, but it is offering an awful lot of money. Kerching!

Jamie Oliver would argue that his association with Sainsbury's is a good influence on the chain. Recently he made a Sainsbury's TV commercial with Dame Kelly Holmes, promoting healthy food for children. He did a big promotional push on fresh herbs and properly matured British beef. But diet trends show an increase in the intake of calories from sweet and fatty foods and higher consumption of both convenience and fast food: millions enjoy watching and are inspired by celebrity chefs, and aspire to cook, but cooking with fresh ingredients does not become a habit.

Big advertising deals are not thick on the ground. Big brands and multinationals are very cautious about signing a deal with a TV personality, because it can backfire. "An advertiser can become a hostage to fortune," says Bill Muirhead, a founder partner of M&C Saatchi. "As a rule I tend not to use personalities in advertising, because they can do bizarre things that are negative to and damage your brand. A personality can also hold you to ransom," says Muirhead, explaining how Paul Hogan, a reasonably popular young comic when hired to make Foster's lager commercials, put his price up dramatically after his hit, Crocodile Dundee.

Muirhead agrees that up-and-coming TV chefs are anxious about financial success. He was involved in the famous £1m a year deal done between Jamie Oliver and a Saatchi client, Sainsbury's. Oliver, a phenomenal success on television, was not so financially successful. Sainsbury's offered its deal just ahead of Oliver's wedding. Future security must have been on the young man's mind. He believes, however, that Oliver's intentions were good. "Yes, he wanted to make money, but that is not the same thing as greed."

Oliver is a good egg, but not averse to selling his brand. While he despairs at persuading fat Americans to eat healthily, the naive are being flogged everything from body balm (£16) to nesting boxes (£18) and a Nintendo DS cooking game (£28.99). He is worth an estimated £50m.

Chefs who go for big-time endorsement will not have to worry about money any more, but they will have to accept that the big deal will invite negative comment from their peers. And they hate it. The merest whisper of the words "sell out" and the whining begins.

Delia Smith is currently defending her decision to take money from Waitrose to appear with Heston Blumenthal in its advertisements. Last week, she told The Times that she accepted the offer because her paymasters "weren't going to ask me to say 'I love Waitrose'". Delia, hush, please. "I heart Waitrose" is as good as tattooed on your forehead, over the old slogan, J'adore Sainsbury's. Delia and her husband Michael Wynn Jones used to publish Sainsbury's Magazine. Her earnings from the chain were less direct than the Waitrose deal, and she now says haughtily that she "refused to do any advertising". But Delia Smith is a billboard, and she knows it. Her last book, How to Cheat at Cooking, recommended using a number of ready-made foods, including Aunt Bessie's frozen potato and canned beef mince. The "Delia effect" kicked in and they flew off the shelves.

Smith and Oliver have sold more than 20 million books and chefs tell us that the brand or the supermarket will benefit from their good influence. But we can imagine what the answer would be if White asked Bernard Matthews to convert to 100 per cent organic, or Smith and Blumenthal demanded Waitrose cease selling sugary breakfast cereals.

The celebrity chef cult is unique in the world of endorsement because the opportunities are endless. After the books come DVDs, iPhone apps, meal ranges, merchandise, garden equipment, perfume, aromatherapy candles, airline meals, and restaurant concessions in Dubai, New York and Tokyo. Gary Rhodes, Marco Pierre White, Nobu and Aldo Zilli have also put their names to eateries on cruise ships. Oliver and Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall are among chefs who have their own TV production companies.

There is "good" celebrity endorsement. Antony Worrall Thompson sells eco-friendly cleaning products and backs only additive-free foods. Fearnley-Whittingstall speaks out against the power of supermarkets. In the UK, Nigel Slater stays true; in the US, Californian food guru Alice Waters is the purest of the pure. Ultimately, independent thought and advice are at risk. Who can I really trust, when money has changed hands? Can White, Smith and co look me in the eye and say: "This is me speaking, and not my wallet?" I'll wait and see.

Rose Prince is the author of 'The Good Food Producers Guide 2010'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies