Rupert Cornwell: Teachers, the new scapegoats of the right

Out of America: As school standards fall, the classroom has become the latest front in the war over public spending cuts

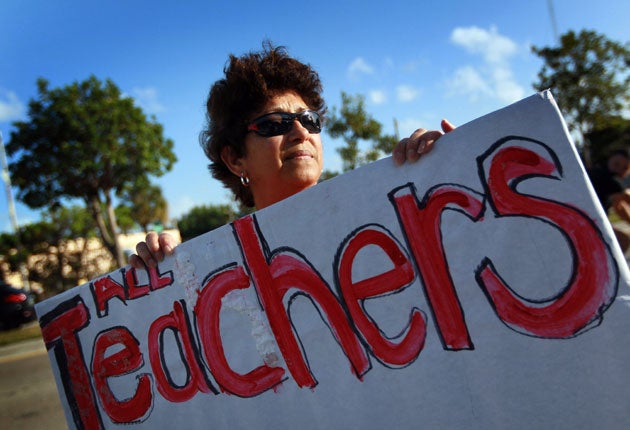

Who, precisely, is the US teacher? Is he (or more likely she) a kind, caring person, driven by a deep sense of vocation that outweighs the meagre monetary rewards on offer – or the fortunate owner of a job guaranteed for life and protected by an over-powerful trade union, whose resistance to change is a prime cause of the crisis of the school system?

The answer is, both of the above, but right now, image number two is winning hands down. Most people can remember their favourite teacher, the one who set an example, who went the extra mile for you, who may even have changed your life. However, in this season of American anger, of state house confrontations, and scarifying budget deficits, teachers collectively are more often seen as greedy villains.

They may not be the best-paid workers in the world. But aren't they usually off work by mid-afternoon, and don't they get three full months off every summer? The rest of us should be so lucky. And they have more than made up for those salary shortcomings with pension and health care benefits that most private sector workers would kill for – and which now threaten to bankrupt the very states and municipalities that employ them.

So, at least, the story goes, as put about by both Republican and Democratic governors who are taking on the teachers and other public sector unions to claw back some of these generous benefits in order to balance their budgets. The Republicans who run Wisconsin, Indiana and Ohio (to name but three states) would go even further, not just freezing pay, trimming benefits and cutting jobs, but stripping the unions of virtually all collective bargaining rights.

Whether they'll succeed, no one can yet say. But everywhere teachers are front-line targets. From California to New York, tens of thousands of them are facing lay-off. In Providence, Rhode Island, all 1,926 public school teachers have been told they will be dismissed (though the vast majority will of course have to be re-hired), while high school students in Idaho – not previously known as a hotbed of left-wing unrest – walked out of class last Monday to protest against the planned firing of 750 teachers across the state.

March 2011, in short, is not the happiest of times for the education profession on this side of the Atlantic. As Erin Parker, a high school science teacher in Wisconsin, ground zero of the assault on public unions, put it to The New York Times, "you feel punched in the stomach".

America's great debate about teachers and teaching is not just over how to stop states going broke, or the alleged Republican plot to break the public sector unions, vital financial backers of the Democrats. For more than a decade now, a far wider debate has raged, irrespective of the party in power. Indeed a rare bi-partisan consensus has emerged. As might be expected, Democrats and Republicans have differing answers – but both agree that if the country is losing its way in the world, education is exhibit A in the "declinist" case.

Not, it should be said, higher education. In every list of the world's best universities, the overwhelming majority are American. And even if you exclude the Harvards, Berkeleys and Princetons, the "average" US college, whether public or private, is a pretty impressive place. The problem lies with the elementary and high schools, more than 80 per cent of them public, where beleaguered teachers such as Erin Parker work.

The US school system is integrated, richly diverse and, with total funding of $550bn (£338bn) a year, hardly starved of cash. But is it doing its most important job, of turning out young Americans who can hold their own in a fiercely competitive and technology-based global economy? The evidence would suggest it is not.

The most closely watched barometer of such matters is the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa), conducted regularly by the Paris-based OECD and comparing 15-year-olds in 34 of the richest countries. In the latest Pisa, released at the end of last year, the US came 14th in reading, 17th in science and a dismal 25th in mathematics.

The results were described by Arne Duncan, the Secretary for Education, as "an absolute wake-up call for America" and proof that "other high-achieving nations are out-educating us and out-competing us". Small wonder that no candidate for state or national office dare be without a detailed blueprint for education reform, and Barack Obama made education the key to "winning the future", the catchphrase of his State of the Union address just six weeks ago.

But he's not the first president to sound the alarm. George W Bush has always pointed to the 2002 law "No Child Left Behind", requiring states to set measurable standards for school performance, and holding schools directly accountable if they failed to meet them, as his proudest domestic achievement.

Obama has countered with his own initiative, called "Race to the Top", which rewards states that perform well in education with extra funds, while more than 40 states have experimented with "charter" schools, publicly funded but exempted from many regulations on condition they meet specific goals. A few have introduced more controversial voucher schemes, that allow parents to use tax they would otherwise pay for public schools to help meet tuition in private schools.

All these ideas have one goal in common – to bring a bit of private sector rigour and accountability to the public education system. For teachers they mean greater scrutiny of their performance and less security of tenure. No longer would their job be a sinecure; if they didn't measure up, they could even be fired.

Not surprisingly, the teaching unions, both local and national, have opposed some of these proposals – and, as with health care, it is debatable precisely how far the disciplines of the marketplace should be applied to education.

But one thing is sure. The bitter budget battles in Wisconsin and elsewhere have opened a new front in America's education wars, placing teachers and their unions under pressure as rarely before.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies