Tim Lott: Blame the bullies – but don't forget those who let them get away with it

Rupert Murdoch – the Great Bully – may fade from view, but as long as the frightened and the craven give in, their tormentors will thrive

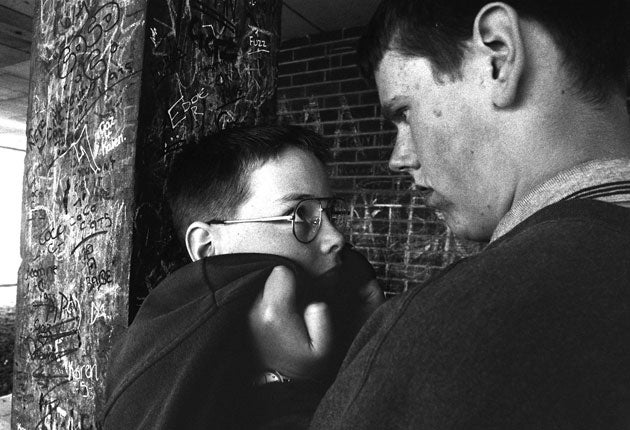

As anyone knows who has suffered their unwelcome attentions, the spell of the bully is hard to break. Whether in the schoolyard or the boardroom, bullies are powerful, invariably surrounded by a loyal clique, and ruthless in maintaining their dominance over others.

The collapse of the power of the greatest bully of our times, Rupert Murdoch, is thus profoundly refreshing and enabling. The clique falls – the resignation of Rebekah Brooks means the bully can no longer protect its members – and the bully is fatally diminished. The spell is broken because the power of the bully rests not just on actual power, but also on perceived power.

Anyone who, in the past, wished to face down Murdoch had to deal with not only what he would do in response, but also what he might do. For bullies are by nature ruthless, spiteful and vengeful (I even now think that the ending of the News of the World was as much an act of spite as an act of brand cleansing). Can there be a single member of the British establishment who lacked a scrap of dirty laundry that they feared the Dirty Digger might uncover if they defied him?

Because of their power and their malice, the defiance of a bully of any stripe requires courage – and that is a quality that has been singularly lacking in our politicians throughout this sorry saga. It is often said that bullies are cowards, but it is sometimes the case that the bullied are also cowards. Post John Major – who would have no truck with Murdoch – the enabling of this dynamic by politicians has been almost universal. The only cabinet politician in this administration who tried to defy Murdoch, Vince Cable, was slapped down by his craven boss – the same boss who is so suddenly overcome with righteous anger. The same unconvincing froth has been displayed by Gordon Brown, who sucked up to Murdoch like all the rest before the mob rose up.

Ed Miliband has been respectable in distancing himself from Murdoch even before the crisis, but when Labour was in power, like the rest of his colleagues, he made barely a squeak. And it is this collective cowardice that bullies feed on, the cringing in the face of perceived power. It would be nice to say that in the past few weeks Parliament has found its nerve, but it would be truer to say that it has been swept up in a storm over which it had no control.

Martin Amis once wrote about a murderer having a "murderee" – who courted their own destruction. And perhaps all bullies have their "bullees" – the craven and the cowardly that the thug can sniff out and exploit. It is ironic that Gordon Brown, with all his ex post facto outrage, wrote a book on the subject of courage. But in reality, the political classes have courted their fate in the way that many of the bullied do – by cringing and showing their deference in the face of power.

Bullies are only vulnerable when they are openly and comprehensively defied. And in this, Westminster has singularly and overwhelmingly failed. Who can doubt that Murdoch could have been taken on and defeated many years ago, if we, together with the politicians and the police, had seen the scrawny nakedness behind the Emperor's New Clothes and called his bluff?

However, while the Great Bully may be fading from view, bullying will continue. All societies, all cultures probably, are bully cultures, because some of the powerful will always abuse their power. After News International has taken a fall, we are less of a bully culture, but the bullies are still out there, both individually and collectively.

The individual/collective distinction is an important one because, while there are individuals who are inclined to persecute the weak because it makes them feel better about themselves (or whatever psychopathology of bullying you adopt), there are also collective, institutional bullies who act as a pack, and whose inner workings foster, tolerate and even encourage bullying.

Foremost among these, also highlighted this week, are the police. Quite apart from anecdotal and personal evidence about their behaviour, which is often arrogant, inappropriate and heavy-handed, clearly they have a bully culture that stretches into the past and is still flourishing.

The bullying of legal protesters, such as UK Uncut, the ruthless striking down of Ian Tomlinson and, of course, the police's ready signing up to Rupert Murdoch's project, are all evidence of a culture far too sympathetic and tolerant of bullying.

Organisations such as the police, in granting lightly regulated power to many thousands of individuals, are bound to attract those who like to push people about. So this is a time to think about not just media and political culture, and not just police honesty and corruptibility, but also the inappropriate use of police force – or, to put it plainly, institutional bullying.

Given that politicians are routinely accused of just about anything when it comes to moral territory, most people would probably suggest that politicians are bullies, too. I'm not so sure that they are the worst offenders, though – at least in democracies. Certainly, it appears from all accounts that Gordon Brown was a bully on a personal level towards his aides. Alastair Campbell was no wilting violet either. But most politicians are constrained in the way that police and media barons are not. They may bully, but they cannot be seen to bully. It's bad for their image.

The most common form of political bully is the dictator – from Hitler, Stalin and Mao to all their lesser impersonators. Surrounded by cliques and flattery, their propensity to inflict cruelty and their own values on everyone can survive unchecked – until revolution, with any luck, finally defeats them, Ceausescu-style.

Whatever the institutional ramifications, some might think it matters what the pathology of the individual bully looks like. Personally, I cannot say and do not much care. Theories abound about what makes a bully, from having been bullied themselves, to the lack of parental attention, to a lack of self-esteem. (I am rather more inclined to believe inappropriately high esteem leads to bullying.)

Whether or not being a bully is psychologically explicable, it is not excusable. The only academic fact of any interest I can come up with about bullies is that they have a far higher chance than the normal population of being incarcerated. Perhaps it is too much to hope for that Rupert Murdoch might follow in the path of Conrad Black. However, if Andy Coulson should find himself in the cells, and James Murdoch is under investigation, who knows where it might end?

This leads me to a particular fantasy, which may never play out but for me at least is a satisfying one, for the fantasy of revenge against the bully is a powerful one. If Rupert Murdoch continues to fall, and thus resemble more and more the pathology of Charles Foster Kane, one can only imagine that he might finally, as the veils of death approach, have his Rosebud moment, in which he grieves for his lost innocence. As the reporter Jerry Thompson observes at Citizen Kane's demise: "Mr Kane was a man who got everything he wanted, and then lost it. Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn't get, or something he lost."

One columnist wittily suggested that the word Murdoch might mutter on his deathbed would be "Redhead". But I suppose we all hope that justice for the wrongs that any tyrant has done will finally come, if only in private and in the soft, dark space of a man's own brain.

Murdoch, whatever happens now, will go to his grave largely unmourned by millions and hated by many – a legacy crystallised when one of our greatest writers, Dennis Potter, named the cancer that killed him "Rupert". Potter's is not, perhaps, an inappropriate "tribute". For it was Murdoch, more than anyone else in this country, who encouraged the bully culture.

We may celebrate now, but the true celebration will only come when the political classes prove that they can hang on to their (very) recently discovered guts. Then we could have politicians we respect, and who, moreover, respect themselves.

It's an ill wind that blows nobody any good, and if such an unlikely revolution in values comes to pass, then the whole sorry Murdoch saga will have had at least one profoundly important outcome. But I wouldn't pin too many hopes on it happening – because if bullying is a universal tendency, so, sadly, is the temptation to succumb to it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks