The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

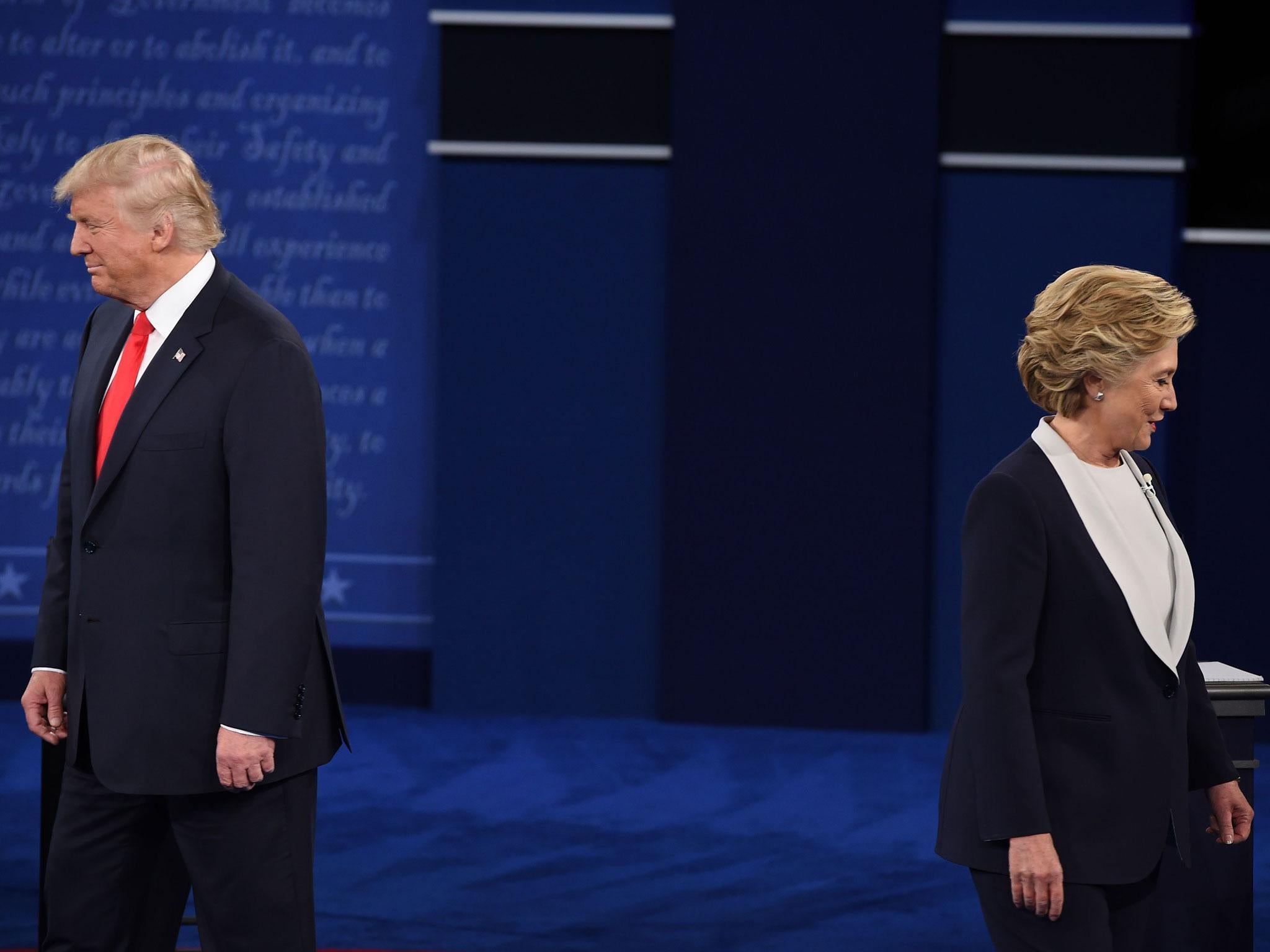

These are the policies that Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton actually stand for

It would appear that the smoke from the fireworks of a multitude of sensational revelations conceal gaps in our understanding about what either candidate’s presidency would mean for the rest of the world

If there is one thing that the current US election cycle hasn’t lacked, its bluster, noise and full blooded argument. But yet for all the uproar generated by the opposing sides, there have been deafening silences. The Trump campaign has been consistently accused of a paucity of detail when it comes to actual policy, but both candidates have taken advantage of the lack of practical prescription afforded by an election so rooted in arguments about personality and values as opposed to politics.

One of the most noticeable gaps in this particular election cycle has been in foreign policy. While the topic of “foreign-ness” has been a central theme, the concept has been much more grounded in identity than geopolitics. Namely inward facing questions relating to who is foreign, and what is to be done with them. The outward facing questions, perhaps understandably, have been never seemed to gain as much traction. Foreign policy issues have been discussed, but candidates have not been scrutinised as heavily on it as in other areas, tending to get distracted by issues of personality and temperament of the person “holding the launch codes.” It would appear that the smoke from the fireworks of a multitude of other sensational revelations conceal gaps in our understanding about what either candidate’s presidency would mean for the rest of the world.

Trump is perhaps the easy target here. For months he has talked about America’s relationship to other countries with a level of casual dismissiveness that has drawn scorn from just about every corner of the foreign policy commentariat, and even from within the military hierarchy. His threats to NATO and other allied states that they run the risk of being told “congratulations, you will be defending yourself” if they don’t start contributing to the cost of maintaining America’s global military nexus left many a policy wonk’s jaw on the floor. But this bluster, or his accusation that Clinton facilitated a $400 million cash transfer to Iran during the 2015 nuclear deal, or his constant referrals to China’s theft of American jobs and intellectual property, are all mere extensions of the central element of his domestic campaign message: ‘We are being ripped off by everybody.’

We don’t know whether President Trump could actually do much to address the age old problem of freeriding within security communities, or whether he could reverse a Security Council sponsored nuclear deal with Iran, or implement the type of protectionist measures that would restrict off shoring of American labour. With much of the US political establishment openly hostile to him, major shifts in existing policy might be a tad ambitious. Either way, there has been little concrete discussion of if or how such things could happen, and nor is there likely to be.

What we could expect in the time remaining is some insight into the candidate’s potential responses to the most immediate fault lines in the international system. NATOs relationship with Russia for instance, has hit its lowest ebb in recent history due to the intransigence of the Syrian conflict, and the apparent inability of any peace arrangement to wrest the area free of intersecting foreign and internal interventions. We’ve witnessed the spectacle of Russian naval presence in the channel. The US and UK are increasing their military presence in Eastern Europe. Can either candidate make assurances about escalating tensions between superpowers?

Trump’s Russia policy is a bizarre Schrodinger-esque duality, being both conciliatory and aggressive depending on whom on the ticket you ask. Mike Pence made clear in the Vice Presidential debates that Obama has been too weak on Putin, thus contributing to the protraction of the Syrian conflict. Clinton, as Secretary of State within that administration would continue to fail to balance against Putin, whereas Trump would take a much stronger line. But ask Trump himself, and he maintains that he would pursue his own detente with the Russian Premier, and attempt to solve the Syrian conflict by working with the Russian government to stabilise the region and fight Isis. This would seem an intolerable level of internal contradiction, but such is the small role foreign affairs has played in this election that this huge discrepancy can fade into the background.

Conversely, the issue with Clinton’s Russia policy rests on its potential for toughness than reconciliation, contrary to Mike Pence’s claims. The former Secretary of State has always had a reputation for hawkishness. Distracted by the sideshow of the Benghazi hearings, the media has paid much less attention to Clinton’s role as a decisive proponent of the Libyan intervention. She has in private talked down the potential for more overt western military intervention in Syria, but will further military build-up in the region change her perspective? Shouldn’t we know a lot more about where her administration’s “red lines” are in order to understand the risks of further degeneration of relations? The spectre of conflict between the superpowers is a point of global concern and should be treated as an issue of immense importance.

The vacuous nature of Trump’s foreign policy rhetoric has inflicted twin injuries on the electoral discourse. He has lowered the tone in most conceivable ways and in the process reduced important policy questions to trivialities and sloganeering. More importantly, his lack of basic competency has handed Hillary Clinton something of a free pass. In an area where she should, as contender for the most powerful office in the world, be encountering serious scrutiny, she need only hold invoke the frightful alternative than enunciate her own vision. She was receiving much more substantive challenges from Bernie Sanders in the primary.

It is easy to see why political contests bathed in personal vitriol generate cynicism. It’s commonly argued that 2016’s populist grandstanding has given rise to a “post truth politics.” This itself seems like hyperbole. Try to find someone who will tell you that party politics used to be an honest game – I wish you luck. They might argue that things didn’t always seem quite so shrill, and almost certainly social media has had an amplifying effect on the general unpleasantness that surrounds political campaigning. But it has also opened access to the majority for participation in debate.

I think it might be more accurate to say that hysteria obfuscates detail. Hysteria is easier to report than substance, personal attacks are easier to understand than the minutiae of policy, and it makes for better water cooler conversation. It would be quite the idealist that would argue that anything could be done about this aspect of politics; to the contrary, impassioned (reasoned) debate is healthy. But the wonks and “experts” in the media and academia, for the all the hard time they have received in the last year, have a responsibility to not let the noise produced by this debate to provide an escape route for the politicians. There is a social duty of care to provide rigorous analysis of the arguments being made, and to demand an explanation for their absence when they are not.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies