It's shameful that the UN is investigating the UK over extreme levels of poverty

So far from the Blair government’s proud pledge to abolish child poverty by 2010, the goal itself has now been abolished

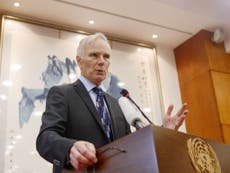

At first glance, the “fact finding” visit to Britain by the UN’s expert on poverty seems a curious excursion. Professor Philip Alston, the UN special rapporteur on human rights and extreme poverty, will no doubt have seen the Office for National Statistics figures which demonstrate that income inequality in the UK has fallen slowly over the past decade or so. Respected independent bodies such as the Resolution Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies reach similar conclusions from their analyses of the data.

The facts, in other words, seem clear. Why then should the professor add the UK to his recent itinerary of China, Romania, Saudi Arabia and Guinea-Bissau?

The answer, of course, is that even though income inequality in the UK has shown an encouraging trend in recent years, it has been largely because the “squeezed middle” of popular political mythology are no longer squeezed, and have in fact done best, relatively, from a decade’s worth of changes to tax and benefits, and rather better than the richest and the poorest households.

The UN will also be aware that, since the 1980s, the UK has evolved into one of the advanced economies’ less equal societies – in disparities in wealth, driven by successive housing booms; in income inequality, where the cult of obscenely high executive pay has been imported from the United States; and in equality of opportunity, with social mobility slowly declining after decades of progress.

Britain remains a wealthy nation by any global standard, and its poor are obviously better off than those in the poorest developing economies. That, though, is not the point. It is relative poverty, and the hidden poverty that comes with detachment from the mainstream economy and political life that are two of the most striking and obvious features of contemporary British society.

The rich have got richer since Margaret Thatcher’s time, and little that the Major, Blair, Brown or Cameron governments did made much difference to the revolutionary changes she wrought on the country. Poverty persists.

Whatever the statistics say, it is also plain that many people now being subjected to universal credit are having to go without because of the inherent meanness of the system and its botched introduction.

A casual visitor to the centre of virtually any town or city will witness for themselves the rise in rough sleeping. A glance at an estate agents window will reveal how difficult it is for young people to achieve the property owning dream many of their parents and grandparents took for granted, or even to rent. Not since the 1950s have the public schools exerted such a grip on the upper echelons of public and corporate life.

If Professor Alston visits the poorest districts, he will see for himself the loss of hope that has accompanied long-term economic decline, and other intangible types of poverty. If he takes the short walk from Kensington to north Kensington in London, he will travel from elegant mansions to the now covered hulk of Grenfell Tower. If he chooses to compare the London Kensington to its Liverpool namesake district, he will see the north/south divide graphically exposed.

He will also discover how badly and disproportionately affected by crime the poorest families are. Most of all he will hear how years of austerity have damaged the public services those families depend on: bigger class sizes, longer waits at the hospital or to see a GP; the police who can’t spare the personnel to investigate crimes; and costly university education.

So far from the Blair government’s proud pledge to abolish child poverty by 2010, the goal itself has now been abolished (though the Scottish government has reinstated a target).

In fact there are so many facts for Professor Alston to find on the streets of Britain that he could spend many years exploring the truths about British society. It will no doubt fall outside his remit, but the rest of us might also reflect on who is likely to be made victim of the bill for Brexit – higher prices, lost jobs and further cuts to public spending, services and benefits.

Perhaps Professor Alston’s name will rank alongside Engels, Rowntree, Tawney, Toynbee and Beveridge in the pantheon of pioneering research into the living conditions of the poorest in Britain. His report, when he makes it, is likely to make for uncomfortable but essential reading.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies