Immunotherapy: The secret of teaching the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells

It is increasingly apparent that the immune system naturally attacks cancer cells, which are probably produced all the time in the body

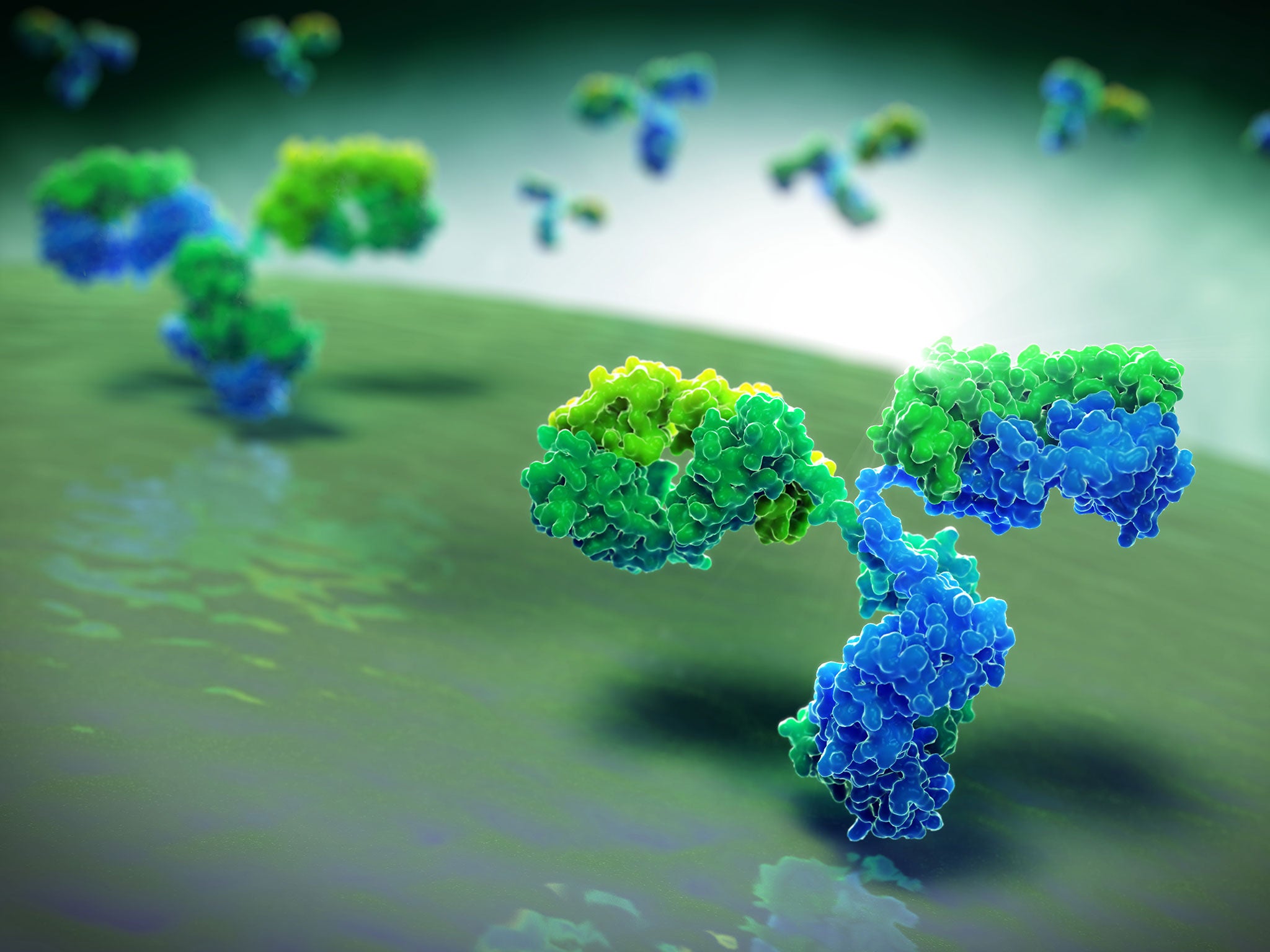

Immunotherapy is seen as one of the greatest advances in cancer treatment in decades. The essential aim is to stimulate the body’s own immune defences to correctly identify and destroy cancer cells while leaving healthy cells untouched.

Scientists are following various approaches using both antibodies, which are the proteins produced by the immune system to attack invading viruses and bacteria, and T-cells, which are the “cellular” part of the immune response – which also targets pathogens within the blood and lymphatic systems.

It is increasingly apparent that the immune system naturally attacks cancer cells, which are probably produced all the time in the body. So the rationale is to boost this inherent process of clearing out rogue cells that have become cancerous.

Because the immune system is such a powerful killing machine, it has to be carefully controlled by the body to prevent it attacking healthy cells. It does this using “checkpoints” or molecules on certain immune cells that have to be activated or inactivated to start the immune response.

Some immunotherapy drugs, called checkpoint inhibitors, work on these checkpoints, effectively releasing the brakes on the immune cells so that they can attack cancer cells. Trials with such drugs, for instance nivolumab and ipilimumab, have had promising results.

Another approach is to involve T-cells, which are a type of white blood cell, in the targeting of cancer cells. One way is to attach chimeric antigen receptors, which are designed to recognise certain cancer cells, to the outer membrane of a patient’s own T-cells and then transfuse them back into the patient.

A similar method exploits the T-cells’ own T-cell receptor protein, which can be genetically manipulated to attack cancer cells. This is believed to be particularly useful in treating solid tumours – which are more difficult to combat than the “liquid” tumours of the blood and bone marrow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments