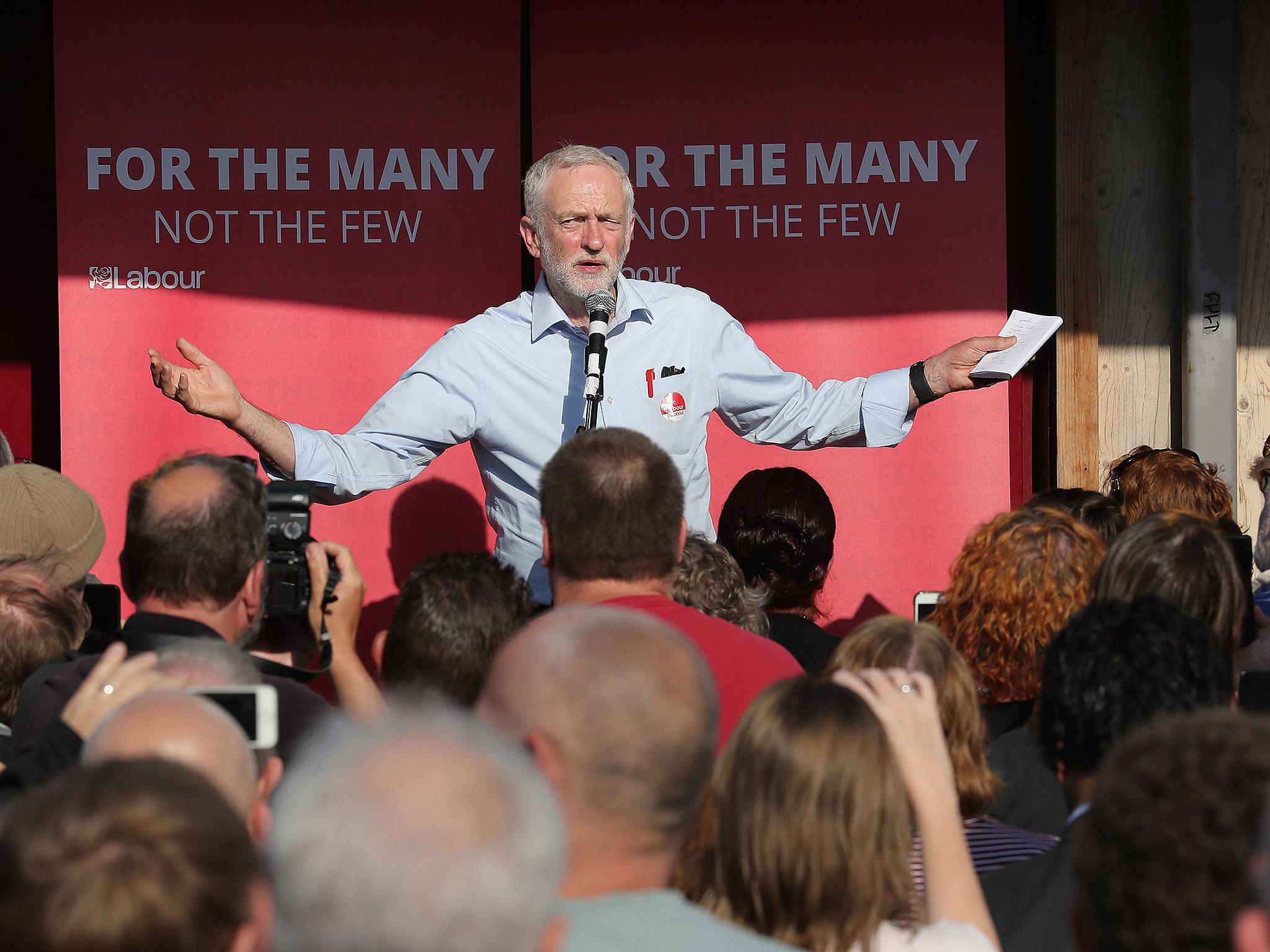

Jeremy Corbyn is right: we can be honest about the causes of terrorism while still refusing to justify it

Politically unpopular or not, this kind of conversation is vital if we are to take terrorism seriously, and if we are to hope effectively to combat it. I know: I've spent years researching terrorism

Jeremy Corbyn has today called for us to address the causes of terrorism in order to try effectively to counter it. Perhaps predictably be has been accused of “justifying” terrorism by doing so, and criticised for crass timing and opportunism. However, the truth is that decades of research suggest Corbyn is quite right.

The causes of terrorism are complex, and differ significantly from case to case. However, this does not mean that we cannot identify and challenge them. More than 30 years ago the renowned political scientist Martha Crenshaw argued that there are both preconditions for terrorism, and precipitants of terrorist acts. Preconditions relate to what we might call root causes: factors over the longer term that set the stage for terrorism. Precipitants are linked to a particular event: factors that might be said to be “triggers” for the terrorist(s) involved. Both the preconditions and the precipitants may vary (in nature, impact, and extent) from case to case.

The fact that terrorism has a variety of causes, and that these might differ from situation to situation, certainly makes countering terrorism difficult: we have to account for variation, we cannot treat every person vulnerable to radicalisation as if they were the same, we cannot find comfort in simplistic narratives of hate, poverty, ignorance, or alienation.

Instead we have to embrace complexity, and we have to make counterterrorism law and policy on the basis of research, evidence and expertise. We also have to then commit the resources that are needed to make those policies and laws effective, and we have to be willing to evaluate them and to change course if it turns out they are not working or are counterproductive in some unforeseen way.

However, politics truly struggles with this. One can, perhaps, understand why. As the reaction to Jeremy Corbyn’s remarks today shows, it is not considered politically tolerable to question accepted wisdom in the field of counterterrorism, or to argue that terrorism may have causes (as opposed to “justifications”) that our actions might be contributing to. Politically unpopular or not, however, this kind of conversation is vital if we are to take terrorism seriously, and if we are to hope effectively to combat it.

In most other policy fields, we expect government to act on the basis of evidence; to survey the research, to consider it in context, to forecast the possible outcomes, to make the best laws and policies they can on the basis of this, to evaluate those laws and policies after some time, and to change them if they are not working. In the field of counterterrorism, however, this is perceived as weakness rather than prudence. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Right now, much of the UK’s approach to addressing the causes of terrorism at home builds on discredited and overly simplistic theories about the so-called “escalator” from religious conservatism to “jihadist” terrorism. As a matter of fact, we know that this theory simply does not reflect reality, and yet we still make policy on the basis of it, not least the pernicious and potentially counterproductive Prevent programme.

Not only that, but the UK’s approach to countering terrorism is piecemeal and fragmented: the connections between, for example, stripping resources out of key state institutions (education, healthcare, policing), increasing surveillance, engaging in military action abroad, and privatising security at home seem simply not to be drawn.

While one cannot claim a firm causal link between Foreign Policy A and Terrorist Attack B, one can surely accept that it would be astute to commit to joined-up thinking about how the whole range of policy decisions that have implications for multiculturalism, belonging, engagement, material wellbeing, participation, openness, education and so on might, taken together, address or exacerbate the causes of terrorism.

Doing this does not preclude the everyday and vital work of intelligence-gathering and policing which is remarkably successful in protecting us from terrorist attacks on an everyday basis. Instead, all of these things need to happen together, in an evidence-based way, if we are effectively to address the terrorist threat.

Reams of peer-reviewed research, often funded by governments themselves, show that taking terrorism and counterterrorism seriously requires a focus on causes, evidence and evaluation. It also requires substantial resourcing across policing, security, education, community services, and welfare, as well as long-term thinking in policymaking and foreign policy.

In raising the question of addressing the causes of terrorism, then, Jeremy Corbyn has been neither crass nor opportunistic but, rather, insightful in taking seriously the challenges of countering terrorism and enhancing our collective security.

Fiona de Londras is the Professor of Global Legal Studies at the University of Birmingham

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks