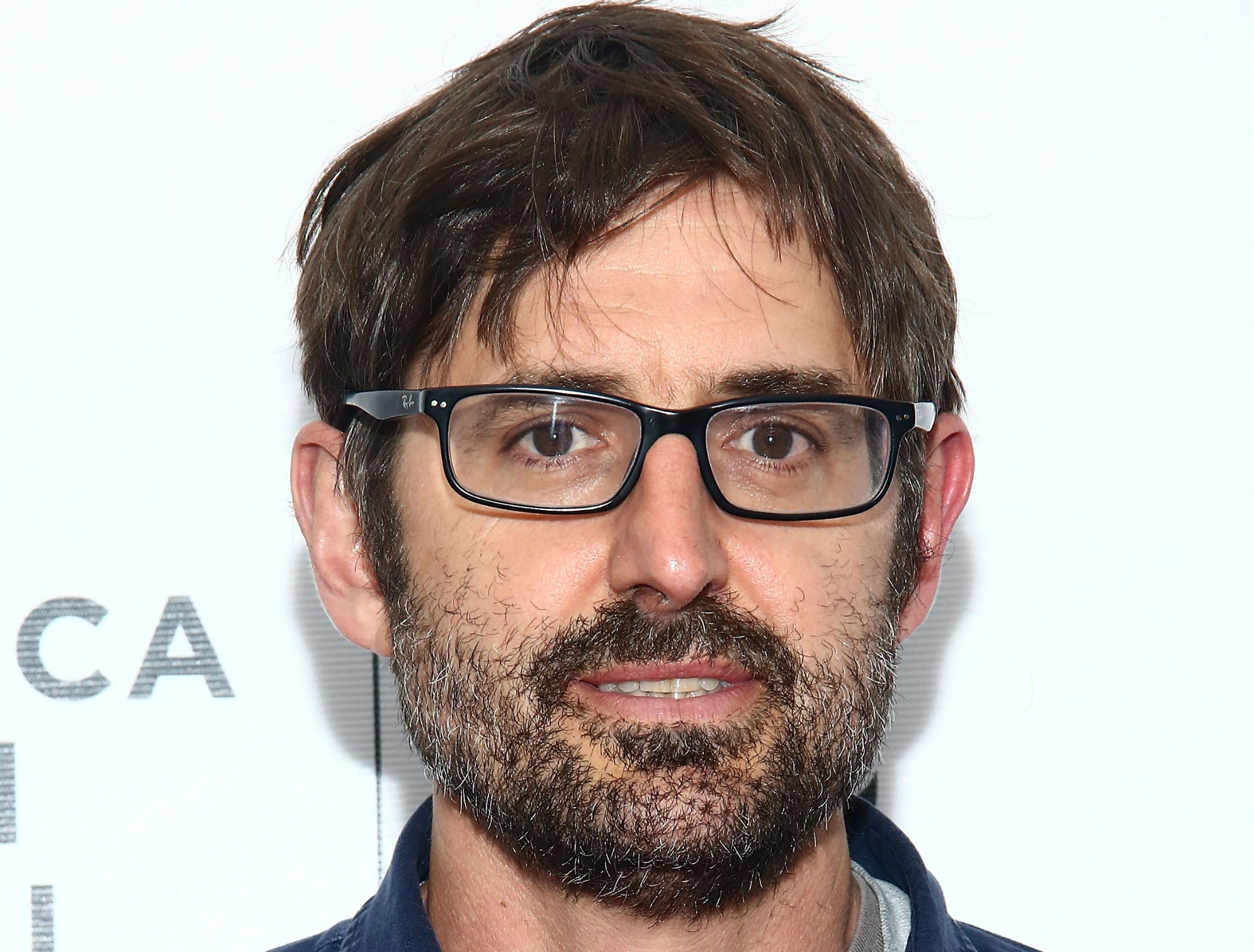

Louis Theroux’s soul-searching over Jimmy Savile proves that journalism has a conscience

Glowing media profiles of a person who turns out to be a rogue cannot help but look bad in the cold light of day. But actually can any of us, journalist or otherwise, honestly say we have never got someone wrong?

When I was about twelve my younger brother wrote a letter to Jim’ll Fixit, asking Jimmy Savile to fix it for me to play cricket with one of my sporting heroes – probably Mike Atherton. Needless to say, no fix was forthcoming, which as it turns out was maybe for the best. At the time though, it was pretty gutting, as much because I loved Jim’ll Fixit as for any lost chance to bowl Atherton my best leg-break.

It’s hard to find anyone now who doesn’t say they always thought Savile was creepy. I didn’t. Odd, perhaps, eccentric undoubtedly; but basically he just seemed to make cool stuff happen on telly. Then again, I was child watching the box. I didn’t know him, I never met him and frankly I had little idea that any adult could be abusive in the way Savile clearly was. As it turns out, many less naïve people were similarly oblivious, until the grim truth finally tumbled out four years ago.

Louis Theroux’s 2001 documentary about Savile painted a remarkable portrait of the man. I was working in London by then and I remember watching it with my housemates and being bemused by how he kept his dead mother’s clothes in a wardrobe. Clearly Savile was even weirder than we all thought. But anything worse than that? Well, nothing definitive – he was an enigma, seemed to be Theroux’s conclusion.

Having had such close access to his subject, it is perhaps understandable that Theroux has felt the need to search his soul in the time since Savile’s crimes were uncovered. As a renowned documentary maker, should Theroux have seen through the façade, picked up on clues which might have betrayed the real Jimmy Savile? His second film, shown by the BBC on Sunday, examined these questions – and was arguably more disconcerting than the programme he made fifteen years ago.

It’s easy of course to be wise after the event. Comments which Theroux thought unrevealing at the time now take on a different, darker meaning. Footage of Savile hugging two women at a Leeds restaurant, overlooked in 2001, is suddenly grotesque. Yet as Theroux has said, Savile was always plausible, despite – or perhaps because of – his eccentricity. And there was never a smoking gun; just the endless cigars. What other conclusion, really, could Theroux have drawn back then?

One consequence of the exposure, however belatedly, of Savile’s criminality, and the abuse committed by other celebrities including Rolf Harris, Stuart Hall and Max Clifford, was a sense that somehow the press was especially to blame for not having shone a light on their activities. Indeed, the failure of tabloid journalists to unearth a monstrous paedophile such as Savile was occasionally portrayed as the equal and opposite ill to the hacking of innocent people’s phones. It’s a rank, and rather unfair over-simplification – and to an extent is as much a product of low trust in journalism as a cause.

Theroux’s soul-searching ought to provide a corrective to the general view that journalists don’t give a damn about their own methods and don’t deal in self-doubt. It should also be an example, not only to others in the trade, but more broadly. Glowing media profiles of a person who turns out to be a rogue cannot help but look bad in the cold light of day. But actually can any of us, journalist or otherwise, honestly say we have never got someone wrong, or missed hints of impropriety, or – worst of all – turned a blind eye to behaviour we knew was wrong.

When I was at university I once saw a guy acting oddly in a library. He kept crouching as if looking for books on shelves, but always quite close to people’s belongings: I realised after a few minutes that he was a pickpocket. I should have confronted him, or yelled, or called the police – but for some reason I completely froze, trying to ignore what was going on. When he went into another part of the library I gathered my stuff and left the place, only returning ten minutes later when my conscience finally got a grip to report what I’d seen to the staff on duty. For all I know, he may not even have still been in the library by then.

Whenever I think of my passivity on that occasion – and it pops into my head surprisingly often – I feel utterly wretched. I didn’t act because I was overcome by a pathetic fear; afraid that the pickpocket might hit me (a particularly odd idea), or that I’d cause an embarrassing scene, or that maybe, just maybe, I was wrong in what I thought I’d seen.

So it was with Savile too; and if the clues were better hidden, the impact on his victims was a thousand times worse than those who had their phone nicked by a passing thief.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks