Believe we are heading for a high-wage, high-productivity economy, Rishi Sunak? Think again

The UK is undergoing a sort of reverse economic miracle – evolving into a high-wage, low-productivity economy

Here we have Conservatives – the party of what used to be called realism and responsibility – talking up an increase in unit labour costs, higher wages still to be matched by higher output per worker, an accelerating rate of inflation, and the distinct possibility of a wage-price spiral taking off.

We have shortages, a soaring cost of living, significant unemployment in some places and persisting labour gaps in others, taxes up, public spending up, borrowing up and child poverty on the rise. Britain is the sick man of Europe... it’s all aboard the Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak time machine and it’s back to the 1970s. It’s as if Margaret Thatcher had never lived.

It is the weirdest thing. Wages aren’t going up because the UK has just been transformed by Brexit into the most productive in the world. It’s because of self-evident shortages of workers, some caused by Covid disruption, and all exacerbated by Brexit. Britain is now a shortage economy, and the economic miracle we’re experiencing is a miracle of bad decision-making.

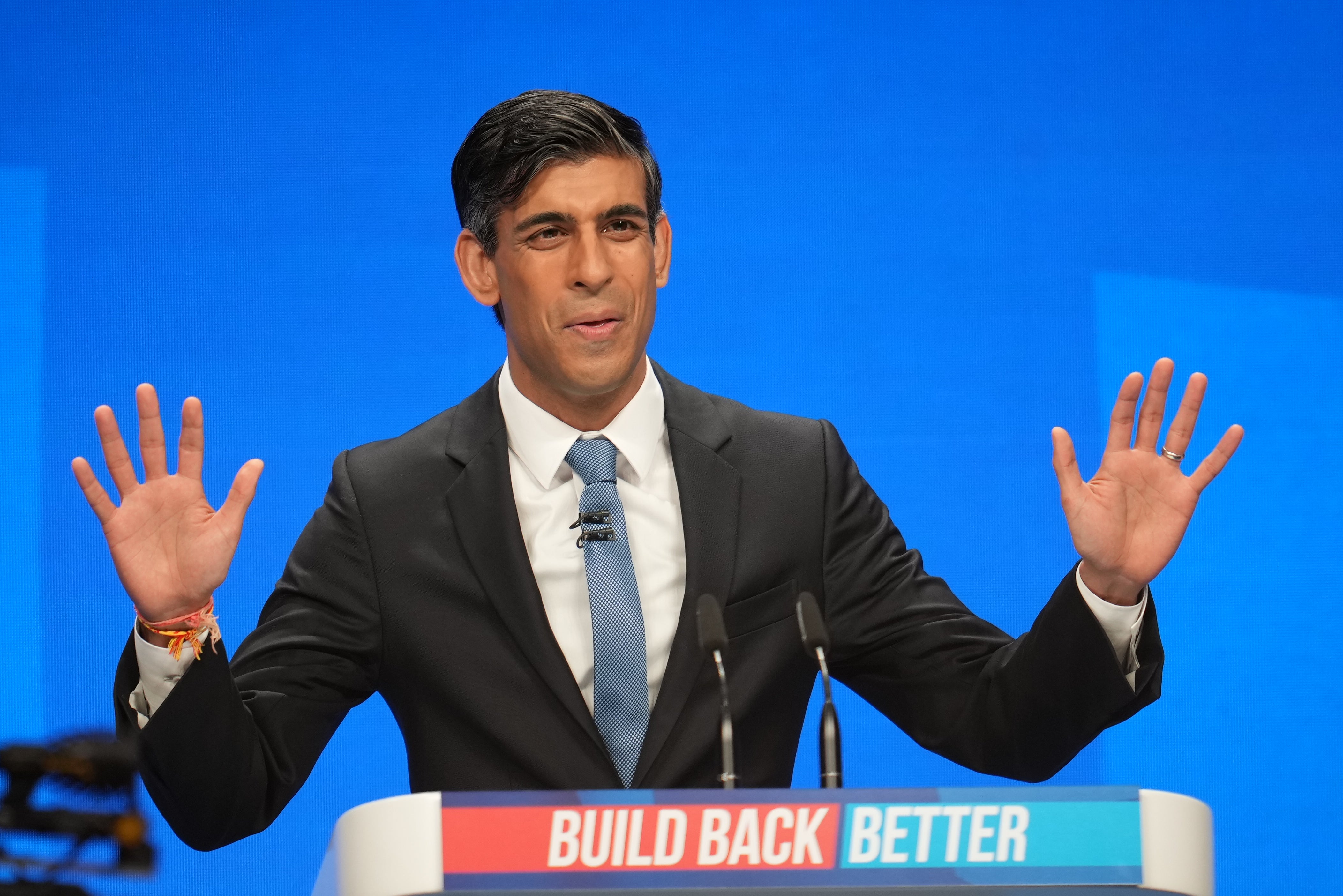

High wages are usually associated with a high-productivity economy, so now Johnson is going round saying that because we’ve got wage rates ramping up in parts of the economy, it means we’re moving towards a higher productivity economy – as if one begets the other. Wrong, at least in the short term. Sunak also told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme that “we want a high-productivity economy, to lead to higher wages, and we’re doing things to enable that”.

Lorry drivers, and others, can demand higher pay packets and better conditions because there’s a shortage of them. They all work very hard – and deserve better working conditions – but they’ll be working no harder tomorrow than they do today. Their trucks will be no more efficient, nor their logistics improved, nor working practices transformed (apart from – one hopes – better truck stops). In fact the government wants to lengthen their working day (though presumably for more pay).

Broadly speaking, lorry drivers will be getting more pay for much the same work. That means higher wage bills from hauliers, supermarkets and the rest. Employers can either try to absorb the new costs in lower profits (bad for future investment and productivity), or they can pass on the increases to shoppers (bad for inflation). Higher wages for some will lead to higher prices. In the case of the public sector the wage bills feed through into higher taxes.

The real wage – what you can actually buy with your inflated pay packet – will remain the same, or even shrink.

But what about the longer run? There are obviously many sectors that need higher wages, but if labour becomes so expensive it becomes prohibitive in the longer run, then one of three things will happen. First, labour could be replaced by capital – machines. The obvious answer, to me, in the HGV driver shortage is autonomous vehicles. The technology is there.

Second, if that can’t be done, as in the more tricky areas of vegetable, fruit or flower picking, say, then the work will simply move abroad, and we’ll get the goods from more economical places, Holland or Kenya, say (as you’ll note if you read the labels in your shopping basket). We will be getting our Christmas turkeys from France and Poland this year, I believe.

Third, where labour can’t be substituted or the work sent abroad, and wage bills become unaffordable, then there’ll be simply less of any given service. This may well happen in social care. If the wage bills in homes escalate then so will fees. If families and tax-payers won’t or can’t pay more, then it means cuts in the standards of care for an ageing population. In all these cases, though, there will be fewer jobs and possibly higher unemployment and poverty.

Elsewhere in the economy, of course, there are no labour shortages but a shortage of jobs caused by loss of markets in Europe – in the Scottish shellfish industry, for example, or perhaps soon in financial services in the City of London. High-productivity, high-value jobs that may no longer be in such abundance.

With fewer workers and a loss of access to its biggest closest markets, it seems obvious that Britain is just going to be producing less and have to accept a smaller, poorer economy. There’ll be adjustments – winners and losers – but what will emerge won’t necessarily be the high-wage, high-productivity economy ministers are parroting on about. It’s going to be the same old low-productivity economy, but now with higher wages and higher taxes.

The UK is undergoing a sort of reverse economic miracle – evolving into a high-wage, low-productivity economy. It may be cheers all round in Manchester because Johnson and his gang have come up with a superficially convincing excuse for the traumas we’re going through – the “growing pains” of “adjustment”, but the reality will catch up with them. Is this the Brexit they promised? Is this the Brexit the UK voted for?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies