Why exactly is the writing on the wall for pen-pushers?

If you need a scapegoat for your cock-ups, or a macho gesture to affirm your austerity credentials, then lay into those civil servants

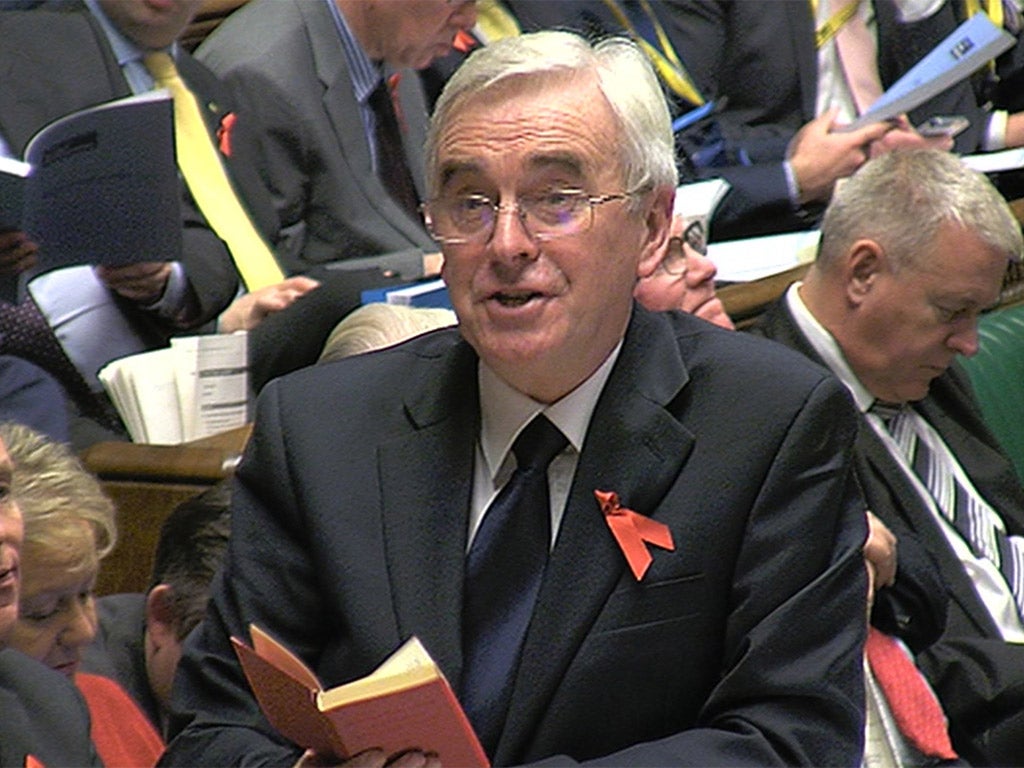

Loud was the mirth on the government benches when John McDonnell flourished Mao’s Little Red Book at George Osborne after the Chancellor had made his Autumn Statement. Heaven forbid that the British state should take lessons in governance – as opposed to hefty cheques for nuclear plants – from China. Power clouds the memory like wine, as some poet of the Tang dynasty should have written. Only a few hours earlier, the Prime Minister had, in a heartfelt memorial, saluted his late aide Chris Martin as “one of the most loyal, hard-working, dedicated public servants I’ve ever come across”, a wise and discreet guide who felt like “someone between a father and a brother for all of us”. Cross-party praise for the former principal private secretary at No 10 echoed Labour MP John Healey’s homage to “a model modern mandarin”.

Now there’s a clue. By the early 1850s, British public administration had sunk into the sloth and dereliction of elite misrule that Dickens satirises as the “Circumlocution Office” in Little Dorrit. In a recent speech, Cabinet Office minister Matt Hancock lamented the “cronyism, corruption and incompetence which riddled government” at that time. So where, via the reforming report of Stafford Northcote and Charles Trevelyan in 1854, did Queen Victoria’s statesmen look for an example of an impartial and professional civil service? Filtered through the meritocratic system that the East India Company had already brought in to tackle its own gross corruption, Britain looked in humility rather than condescension towards imperial China.

Hence “mandarin” became the colloquial English term for a senior state bureaucrat: a lingering homage to the system of open recruitment by competitive examination and promotion on merit that, for all its periodic lapses into abuse, scaffolded Chinese life from 650 to 1905. For about 1,000 of those years, China ranked as the world’s most productive, creative and sophisticated society. Yet its 1,300 counties and 17 provinces depended entirely on a tiny administrative caste selected after a punishing exam-cell ordeal largely for their expertise in classical poetry and Confucian philosophy. Of course, the rigidly trained intellectual parachuted in to run some alien backwater could often lose his footing. Bai Juyi (772-846) has a wry poem called “After Collecting the Autumn Taxes”: “How can I govern these people and lead them aright?/ I cannot even understand what they say./ But at least I am glad, now that the taxes are in,/ To learn that in my province there is no discontent.” Now there’s a poster for the Chancellor’s wall. Despite its drawbacks, the stubborn endurance and consistent achievement of China’s method of public administration is one of the marvels of history.

In Britain, Northcote and Trevelyan’s “Chinese” ideal eventually fell into stagnation and disrepute. Too many suave Oxbridge generalists – spiritual heirs to those scholar-administrators of the Tang, Song and Ming – shone their striped trousers on Whitehall chairs that technocrats and scientists from more modest backgrounds might have put to better use. The Fulton Report of 1968 tried to update Civil-Service thinking and organisation. Still, Matt Hancock can in 2015 bow deeply to the Northcote-Trevelyan principles of “objectivity, honesty, integrity and impartiality”. Much of this week’s political agenda has turned on statistics from the Office for Budgetary Responsibility: a young body, but a classic “mandarin” agency.

So the PM’s tribute to Chris Martin threw into relief the cognitive dissonance that afflicts the post-Thatcher political class. Individual civil servants may be mentors, friends, even heroes. Collectively, they embody a wasteful army of parasites and shirkers who should be cut without mercy whenever – as this week – ministers look to someone else to make a sacrifice.

Need a scapegoat for your cock-ups? Fancy a macho gesture to affirm your austerity credentials? Then lay into those useless pen-pushers in the back office and no one will object.

Not by chance did Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister win millions of chuckling viewers just as, between 1980 and 1988, Thatcherism set about its state-shrinking labours. For all their nuances, Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn’s successive Whitehall sitcoms chimed with a privatising age. Thatcher’s children were taught to see in the higher Civil Service not the liberators and enablers of the post-war welfare state, but devious jobsworths and clandestine power-brokers. On Wednesday, the PM remembered Chris Martin as “my Bernard”, after the sharp and subtle private secretary in the series. Yet at the time, and since, the Bernards got a pretty lousy press – above all from Cameron’s party and its attack-dog media. Maybe he should now find kinder words for all the other Bernards who try to steer the ship of state away from rocks.

The UK currently has 431,100 civil servants. (Thank you, the stalwart civil servants of the Office for National Statistics.) That amounts to a mere 1.4 per cent of all employees. They have median gross earnings of – wait for it, you tabloid scourges of Whitehall fat cats – £24,980. Only about 3,600 rank as senior civil servants, on pay scales from £62,000 upwards. Gross numbers have fallen by 26 per cent since the recent peak in 2005.

No busy citizen disputes the need for smarter, swifter governance. The hi-tech entrepreneur Martha Lane Fox has added her own compelling voice to the roll-out of a wired democracy through advice to the Government Digital Service. Innovations such as the Gov.uk platform, as a one-stop site for access to the state, will shift the nature of Civil-Service functions. What the bureaucrat-bashers tend to delete is the dependence on those “frontline services” that they wish to safeguard on a healthy, flexible skeleton of managerial support.

In the wider public sector beyond Whitehall, anti-managerial rhetoric sounds shrillest in the NHS. Indeed, NHS managers rival new immigrants as the hapless objects of statistical myth-making. According to the King’s Fund health research charity, the NHS spends about 8 per cent of its budget on management and administration. These posts account for less than 5 per cent of staff. In the economy as a whole, managers represent 15 per cent of the workforce.

At the Nuffield Trust, CEO Nigel Edwards and policy analyst Mark Dayan argue: “Far from eating up large chunks of the budget, there is circumstantial evidence that the health service doesn’t have enough senior professional management capacity for such a complex system.” To make up the shortfall, it hires private consultants at a much steeper cost. Besides, those sacred “frontline” professionals almost all perform some admin roles. Taking an axe to specialist managers will add to their burden. “So NHS management is not a group of people; it is a set of tasks, and one that is largely done by doctors, nurses and other clinicians.” Edwards and Dayan warn that the political claptrap of “efficiency savings” misleads. “Big, difficult reductions in these areas are already priced into the health service’s future.” As so often, that snoozing desk-jockey, an idler on our payroll, turns out to be a wraith.

For sure, quality matters more than size. All bureaucracies, public and private, could benefit from incentives to agility and flexibility. But David Cameron’s affectionate homage to Chris Martin pointed up a curious mismatch between the indispensable value of public service and our anti-administrative dogma, with its fantasies of culling battalions of redundant suits. Above all, Britain lacks a high-profile focus for excellence in public management. Look at the erratic history of the Civil Service College. Created in the wake of Fulton’s proposals for a modernised, specialised Civil Service, it became one of the “executive agencies” that allowed Thatcher-era ministers to sideline much of the state. Later, it mutated into the Blair-era “National School of Government”. Now, under its old name, it peddles training courses to foreign or private-sector buyers. It has just hosted 32 senior Indian civil servants. Their feedback forms indicate that they got good value for money. Great – but ENA it ain’t.

ENA, or the École Nationale d’Administration, is the fabled public-sector college set up by Charles de Gaulle in 1945 to rebuild a state wrecked by defeat and occupation. Graduates of the Strasbourg postgraduate school (fewer than 100 each year) have played a decisive role in building fast railways, growing state enterprises, renewing provincial cities – and governing France. Presidents Hollande, Chirac and Giscard d’Estaing are all alumni. Let’s not pretend that the French people love their “Enarques”. To many, they represent a smug elite who mistake their own for the nation’s interests.

Yet the Enarques, like their Chinese forebears, did the job. The next time you complain about a bill from EDF, blame it on the haughty Strasbourg clan: snobs maybe, but meritocratic snobs. George Osborne, self-anointed “builder” of big-ticket infrastructure from HS2 to the Northern Powerhouse, the Midlands Hub and (for all we know) the Devonian Dynamo, will need to dump the cliché of the bloated bureaucrat if he seeks the talent to realise his dreams. For that, the ENA model of a crack squad of sleek fixers in the common good might serve well. After all, a world-class strategist once called for “Fewer and better troops, and simpler administration”. Who demanded that kind of efficiency saving? Chairman Mao.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies