Alexander Calder: Discovering a joyous reading of the experimental artist’s work at Tate Modern

Alexander Calder explored an array of subjects and ideas through his finely-balanced mobile sculptures

Alexander Calder is best known for his large imposing red, blue and yellow stabiles that are placed in front of major buildings in America to add a touch of art to their surroundings. In this major exhibition Tate Modern has chosen to focus on his “performing sculpture” allowing the visitor a surprisingly different reading of this joyous and often disarmingly naughty, yet always experimental artist.

Calder was born at the end of the 19th century – 1898 – in Pennsylvania, the child of painter Nanette Lederer Calder and Alexander Stirling Calder, a sculptor, and he had an elder sister, Peggy. The family relocated to Pasadena, California, when he was eight years old. Shortly after Calder got his first tools and was given the cellar (with a window) as a workshop. “Mother and father were all for my efforts to build things myself – they approved of the homemade.”

By 1923 he was living in New York City and studying at the Art Students League. Two years later he developed an interest in the circus, sketching the Barnum and Bailey Circus, and a year later, while living in Paris, he began constructing the Cirque Calder. Meant to be portable, performed by the artist himself and constructed of small parts, it was a distillation of a real circus, continuing to expand its content until it fit in five large suitcases. Returning from Europe by ship in 1928 he was to meet his future wife Louisa; her “father had taken her to Europe to mix with the young intellectual elite. All she met were concierges, doormen, cab drivers – and finally me”.

By 1929 his circus had attracted Parisian artists including Cocteau and Man Ray. The following year Calder had performed the circus to amongst others Piet Mondrian and then was invited for a studio visit. In 1931 he met Marcel Duchamp who coined the term “Mobile” for his works. Then he went to Spain in 1932 to visit Juan Miró at his farm and performed his circus to the artist and all his farm assistants. This chronology is important for a better understanding of this artist and his influences, which this show illustrates in a compelling and thoughtful way.

We first encounter Medusa (c1930), a suspended wire portrait of Louisa his wife and muse. Medusa was his nickname for Louisa as he had first encountered her on a boat where her hair had reacted to the humidity, this is reflected in this deceptively simple portrait, an unruly curl and a wayward hair that bisects her forehead. The wire works continue with reductive yet recognisable portraits of his artistic circle. Amédée Ozenfant (c1930) resembles Ozenfants own paintings, the wire thicker, blacker and the shapes more geometric then other wire portraits. With a few twists of wire this is elevated from mere caricature to a psychological portrait.

Calder’s performance is captured in its entirity in Jean Painleve’s film of 1955. Calder is shown producing the sounds. It is clear while his audience would be having a good time, he was probably having the best time as he roars like a lion and mimics the faces of the beasts. Nearby a few examples of the circus, include Singe (1928), an abject monkey depicted in wire and wood recognisable as an animal despite its cursory depiction. These objects give a tantalising flavour of what the reality of the entire circus would have been in the flesh. Acrobats (1929) is a wondrous sculpture, in which a male acrobat contorted in a back-bend has a female acrobat standing upon him in the act of doing a walkover. The sculpture manages to capture both his strength and masculinity (his genitals captured succinctly) and her femininity and lightness (she is in a fluffy tutu with just her breasts depicted). Calder’s acknowledgement of his mixture of high and low humour is visible in many of these works, genitalia freely depicted led to both the validity and humour of his comment that his work was more “sewer-realist than surrealist”.

There is a fantastic room of works from the mid-1930s in which several previously un-shown works illustrate Calder’s struggle to bring abstraction and painting together into a third dimension with mobile constructions floating in front of painted panels. Blue Panel (1936) shows the intense blue of a Franz Klein in front of which float biomorphic forms that reference both Miró and Arp. The influence of the colour of Mondrian and the forms of Miró and Arp literally float around this room but they are unique in being Calder’s own language.

The installation of Small Sphere and Heavy Sphere (1932/33) is accompanied by a small video showing the work in action. The engineering and thought that went into this arrangement, so that when set in motion with a special tool the suspended balls – one large, red and heavy and one small, white and wooden – hit the various bottles, tins and box is true poetry, the sounds producing a one-man band of differing tones. I was lucky to witness one of the two curators who have been trained to activate the work. It is extraordinary that something so simple can produce such a beautiful effect both visually and audibly, a true John Cage experience of chance, Cage being another friend of Calder.

This experimentation with forms and movement, abstraction and figuration continues apace through the show. The work Untitled (1934) is a mobile standing within a circle of heavy black metal producing a frame. With movement the mobile consisting of multiple rings produces an optical illusion of intersecting shadows. I recently saw a large installation by Icelandic contemporary artist Olafur Eliasson that shamelessly references the trajectory of this work – showing that Calder’s influence is alive with today’s artists. A mechanised sculpture A Universe (1934) has a more complex geometry. The movement so entranced Albert Einstein that when it was exhibited in MoMA New York he stood before it for the 40 minutes it took to complete its cycle. Calder’s experimentation with materials did not go unnoticed and there is documentation here of some of the larger projects he worked on including a fountain that he designed for the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 Worlds Fair in Paris. The Spanish architect Luis Sert wanted to install a fountain running with mercury to act as a back drop to Picasso’s Guernica. He came to Calder as he heard he might be able to use the material that no one else could use. When Calder was young he took a degree at the New Jersey Stevens Institute of Technology in chemistry and mechanical engineering.

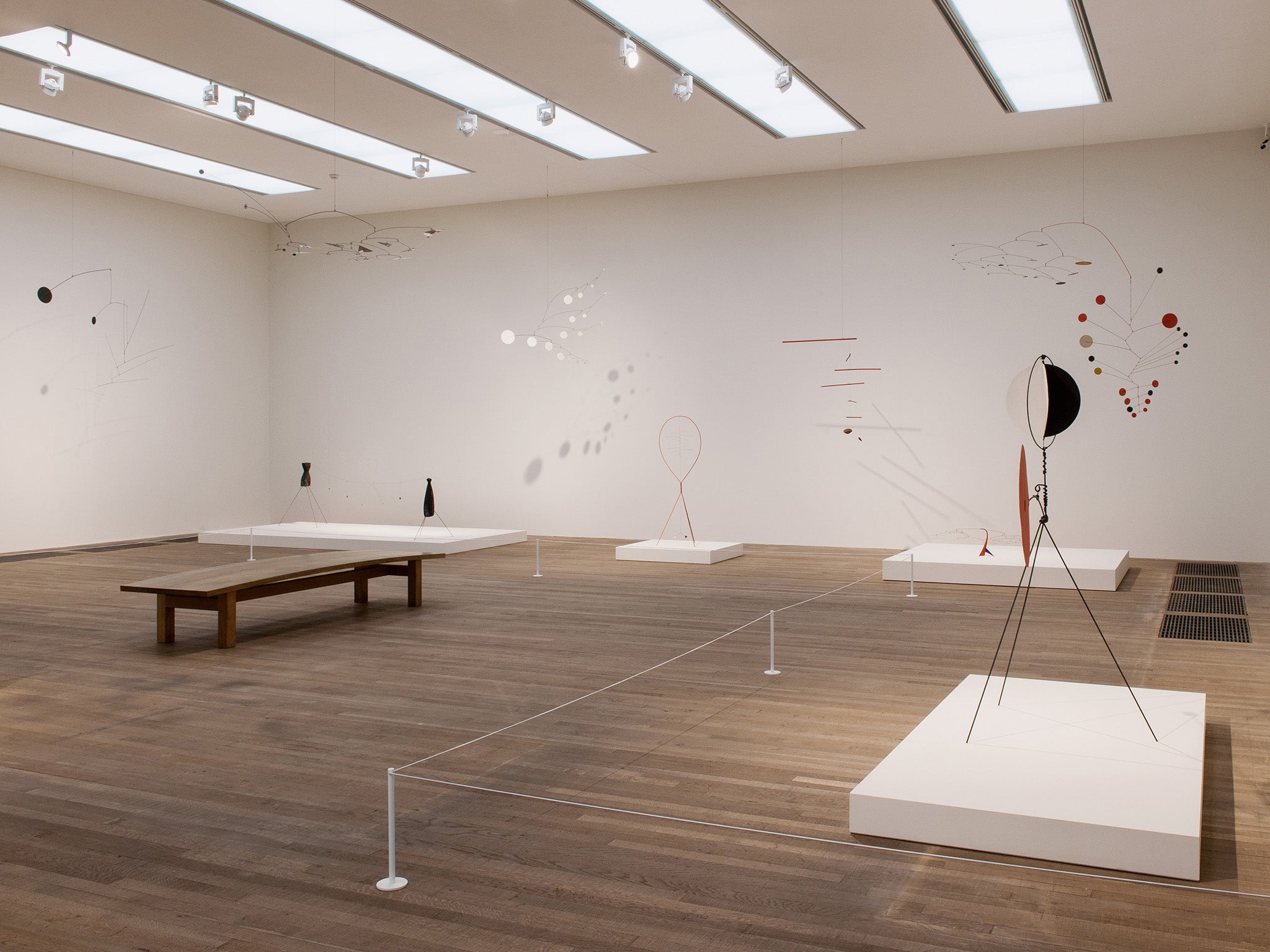

There are many high points in this show but linger in the large room containing many mobiles and stabiles each different. Gamma has graceful biomorphic forms; some, like Red Sticks, are stern with straight lines and show the variety of effects and languages that Calder was playing with. A bench encourages the viewer to pause and wonder at the minimal language employed by this wondrous artist to maximal effect. We may sadly no longer be able to set them in motion ourselves but Calder’s works twirl and gyrate, set in motion by people walking by and the blasts of air from the floor vents.

This is a brave prescient show. A re-reading of the traditional take on Calder that usually focuses on the more “polite” and monumental works, it makes a compelling case for this artist’s brave experimentation. His turning his back on conventions of modesty and hierarchy makes the work feel modern. This is an art that freely admits the low and the high, the bawdy and polite and embraces all tastes both popular and refined. I like the idea of the boy experimenting in the basement of his parents’ house. I wonder how he would feel about how the crude objects he produced are now treated with such reverence.

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture, Tate Modern, London, (020 7887 8888) to 3 April 2016

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks