Andy Warhol, William Burroughs and David Lynch: Obsessive photographers

An exhibition of photographs by Andy Warhol, David Lynch and William Burroughs offers a unique insight into their minds, says Adrian Hamilton

We have grown used to gallery curators digging into the photographic efforts of painters to search out their experiments and inspirations. Now the Photographers' Gallery has gone one step further with a show of the snapshots of three writers and film directors. Not just any literary or cinematic figures, mind you, but a trio of the biggest names in postwar American culture: William Burroughs, David Lynch and Andy Warhol, none of them particularly well known for their photographic work but all of them obsessive snappers in their own way, who have taken pictures through much of their careers in other fields.

Whether that makes them good photographers is another question. It's also the wrong one. Each of them in their own way has taken up the camera as a means of exploring their obsessions, their memories and their beliefs in their own art. None of them, with the possible exception of David Lynch, set out to be photographers as such. It was a means to an end.

Of the three, the most interesting is the writer William Burroughs of Naked Lunch fame. It's 100 years since his birth (he died in 1997) and this is claimed to be the first show devoted to his photographic work. Yet he took snaps nearly all his life with a variety of cameras, processing them in the local chemists before playing around with them in collage, juxtaposition and series. You can see the attraction. For a man who believed in taking words and mixing them up, fragmenting grammar and context so as better to capture sensation and time in verbal form, photographs were the clearest way to achieving the same with visual images.

By the same token, he was quick to turn to collage as a means of giving the photograph a different life by juxtaposing, overlaying and cutting out details. He called them "cut-ups" and "fold-ins", developing the technique with the artist Brion Gysin, whom he met in Morocco, and the mathematician Ian Sommerville, who had evolved the concept of "photo-reduction" in which whole collections of photographs could be montaged and the resulting montage montaged with others until the entire lot was reduced to a single photographic frame.

Ever concerned with time and the manner in which an object or an occasion could contain both the past and the future, he applied this both to portraits of friends but also to shots of locations in which he himself appears, but only as a shadow or implied presence. In another series he photographs a bed before and after sex, the sheets rumpled then stained before the red cover is put back on and the bed restored to tidy anonymity. As time goes on the lure of the composed shot becomes stronger, the pictures more composed and the collages more deliberately arty. He creates montages of his own life and childhood, the edges overdrawn with fierce ink swirls. For Burroughs, who also painted, photomontage was clearly developing as a practice in its own right.

Andy Warhol was an artist already, of course. But from 1976, when he bought a pocket Minox camera, he became a compulsive snapper, shooting as much as a roll a day and then sending up to half-a-dozen frames to "The Factory" to be printed. It was part of his obsessive "diary" keeping of moments, recorded on tape recorder and dictated daily, but also an expression of his belief in the reproducible image as the core of contemporary visual language. He had used Polaroids and enlarged photographs in his prints but now, with a compact instrument of endless versatility in his pocket, he went out to shoot anything and everything he came across.

There was an art to it. Like Burroughs, Warhol was fascinated by photomontage. Where Burroughs was interested in the juxtaposition of images, however, Warhol was more intrigued by their repetition. He would send four or more successive shots of the same object to a seamstress to be stitched together like a cloth. The minute differences in the framing of the repeated picture created a sense of movement and life. He tried the same with different light exposures in a theatrical series of Jerry Hall Reclining on Couch taken in 1976.

His prolific photographic output, however, was largely directed at a form of photojournalism as he shot copious pictures and then assembled them into series on "market", "street scenes", "gay rights demonstrations" and still lifes.

The oddity is his eye. Although people frequently appear in them, and some are of his friends and those he meets, there is a quality of stillness in the shots that makes them peculiarly inanimate. A man in white shorts sleeps face down in one of his People in the Street series as wooden as the struts of the bench on which he lies. A series of photographs of buildings are marked less by what they say than the precision of the composition and the sense of space around. They may have been meant as diurnal records of place but, chosen and printed, they appear as the product of a visual eye increasingly trained by experience.

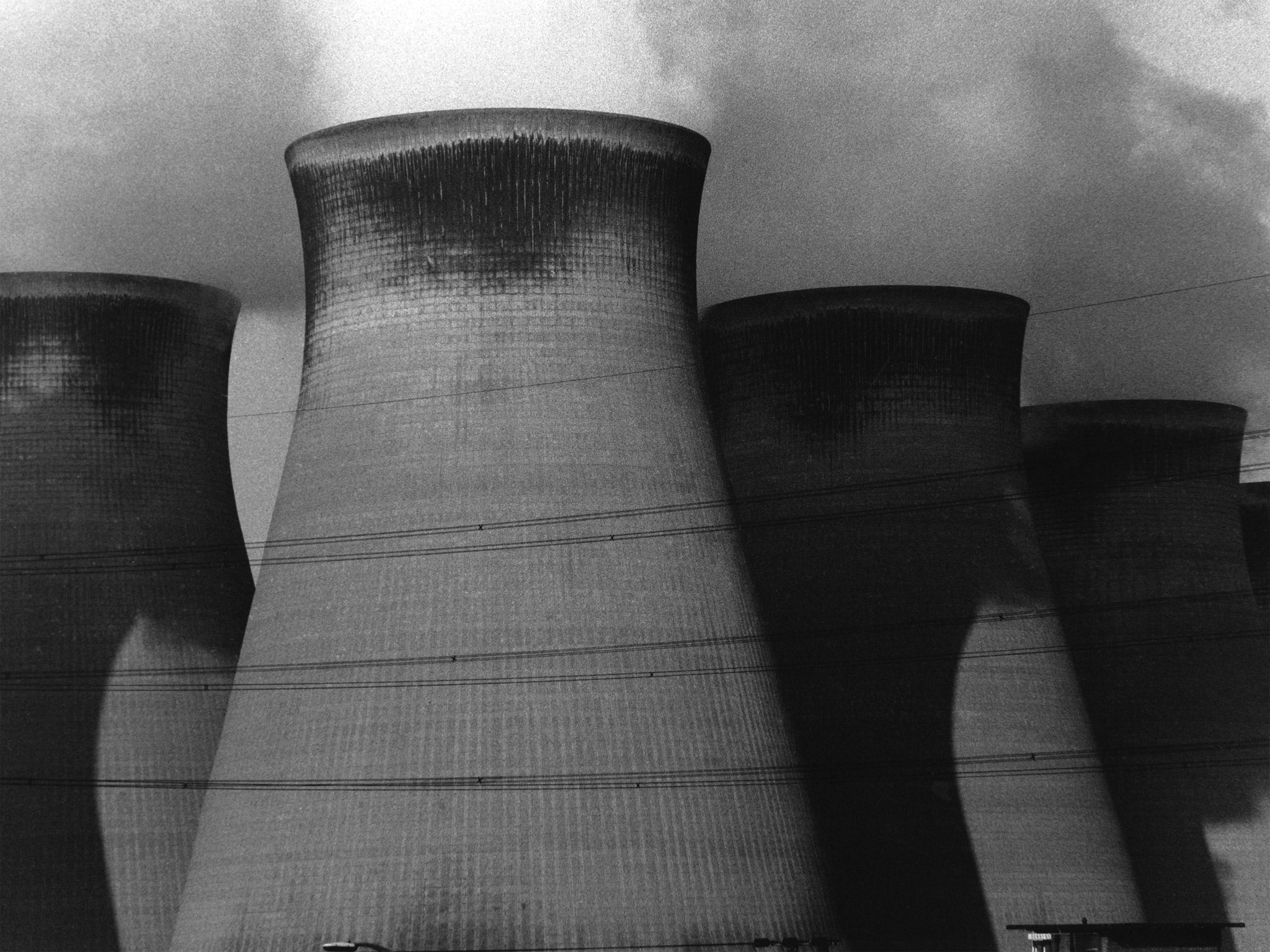

You could say the same about David Lynch's pictures. Throughout Lynch's career he has sought out and taken black-and-white pictures of empty and derelict industrial sites in Europe and America. Displayed here for the first time in Europe, they reflect an eye used to the camera and a mind attracted, as one might expect from the director of such films as Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive, to eerie places of decay and soullessness. Pulling back, the camera catches the clear lines and brute presence of industrial structures. Moving in, it frames the open door, the dusty window and the broken pipe. Far more than Warhol or Burroughs, Lynch's eye catches the detail and embraces the texture of wall, weed and metal. His works are both expressive and monumental, without the presence of man but a product of him.

Industrial landscapes like this have been the subject of innumerable photographic essays over the past half century and more. What makes these different is the sense of the mind behind. Most professional photographers use pictures to tell of place and time, keeping themselves at a distance from the subject. Lynch's pictures tell of a viewer seeking out what connects up with the person behind the lens. Mood is as important as composition.

Interestingly, virtually all the pictures on display here are taken in black and white. You might have expected, given that most of them are from the 1960s and later, that the artists might be more excited by the possibilities of colour then coming in. Yet none of them is. That is a tribute to photography's enduring power as a medium of record. If what you are wanting is a captured memory and an image bank with which to play with form, then black and white does the job with clarity and decisiveness. Colour poses its own painterly possibilities, which seem to have interested none of the three on show here.

Would you be as interested in the results if you didn't know names? Quite possibly not. But then as a way into the mind of three highly creative individuals it's a rewarding show, spaciously displayed on three floors, one for each individual. You will read Burroughs, attend to Warhol and see Lynch's films the better for it.

Andy Warhol: Photographs 1976-1987, Taking Shots: the Photography of William S Burroughs, David Lynch: the Factory Photographs, The Photographers' Gallery, London W1 (020 7087 9300) to 30 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks