Artist Simon Denny’s Serpentine Gallery exhibition brings together the unlikely worlds of tech and art

New Zealand artist Simon Denny is bringing tech culture out of its ring-like HQs and into the gallery. He talks to Hettie Judah

For an artist, Simon Denny has an unusually agile grasp of corporate jargon. Discussing his forthcoming Serpentine Gallery exhibition, Products for Organising, the 33-year-old New Zealander’s chat is peppered with of-the-moment workplace methodologies such as Holacracy and Agile, and the titles of bestselling management publications such as Peopleware and Why Work Sucks and How to Fix it. He’s hot on technology, too, and despite being resident in Berlin, is au courant with Britain’s controversial use of private finance initiatives (PFIs) to fund public infrastructure. These are not common artworld concerns, and yet to Denny, the well-informed and unblinkered examination of the technology and organisations that shape our world are self-evidently pressing subjects about which to make art.

Denny’s interest in corporate structure followed his move from Auckland to Frankfurt in 2007 as a postgraduate student. “This was the year of the first iPhone and I had recently started using a laptop a lot more than I used to as, suddenly, I was living in a different place to most of my friends,” he says. He came to question the background to the devices that were in his hands. How did they get there? How much did he know about the company that made them, its strategy and management policies? What impact did these have on the products it produced, and the way those products delivered information?

From there, Denny began to think more widely about corporate and tech cultures, using his work to investigate the structures, metaphors and graphic identities that they deploy to describe and manage themselves. Over the past few years, his series of large-scale interrelated artworks has included The Personal Effects of Kim Dotcom (2014), in which he recreated an impounded collection of truly terrible art once owned by controversial internet entrepreneur Kim Dotcom, and New Management (2014), in which he meticulously documented the turning point in the corporate operations of Samsung.

It was his installation during this year’s Venice Biennale, however, that really brought him to international attention: called Secret Power and occupying the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana and Marco Polo airport, it examined the contentious information-gathering of the National Security Agency (NSA) via its use of graphics and imagery. Denny commissioned graphics from David Darchicourt, the former NSA designer and Creative Director of Defense Intelligence, who had been responsible for some of the more striking, and, indeed unexpected visual elements in the NSA PowerPoint files leaked by Edward Snowden, including chipper cartoonish illustrations. Darchicourt was unaware that he was being commissioned for an art project, and after he was alerted to the fact by a British newspaper Denny contacted him to chat it through and offer him a trip to Venice to see the work. Darchicourt did not call him back to take him up on the offer.

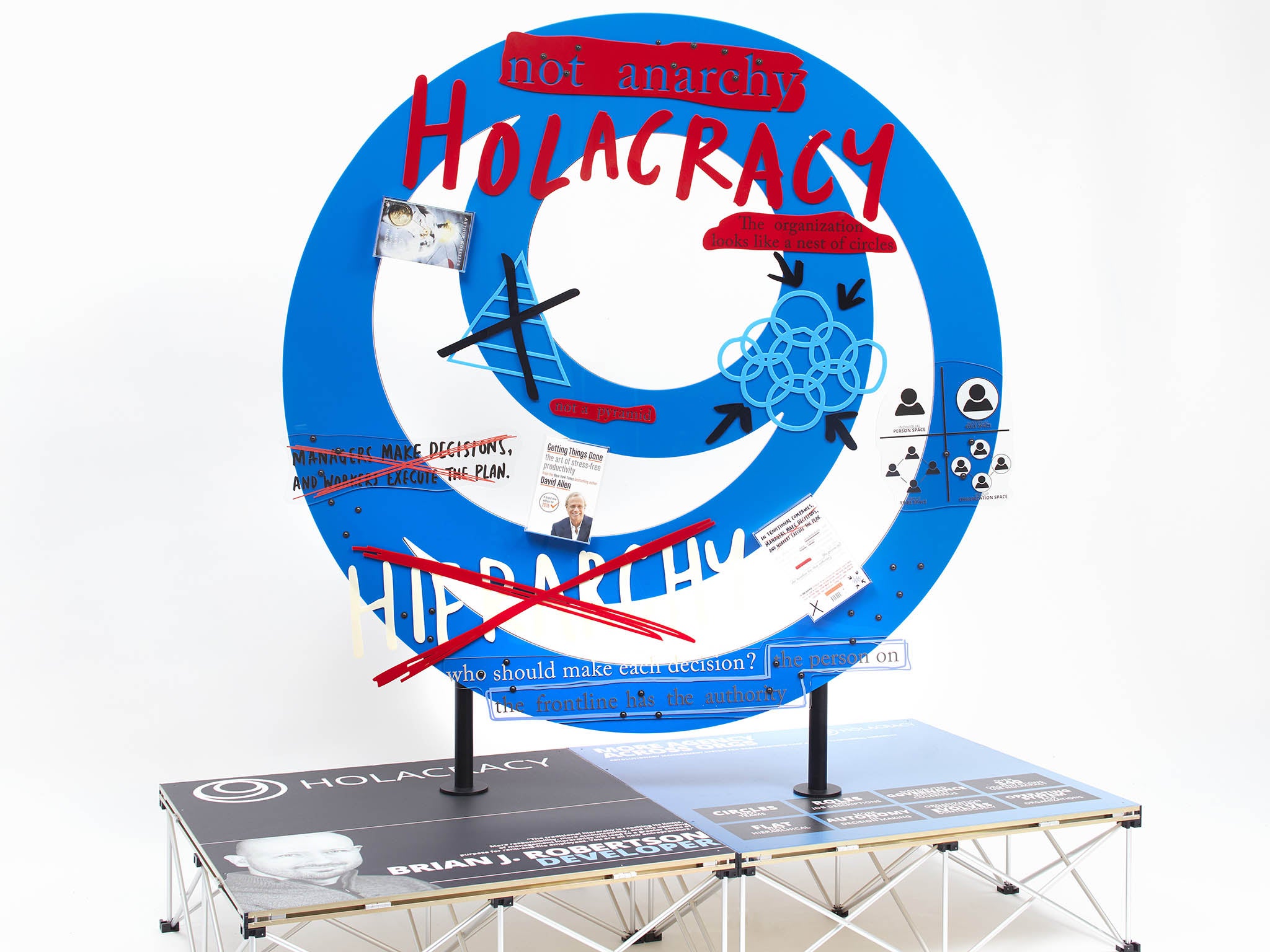

His latest work, Products for Organising, finds the artist using the two sides of the Serpentine Sackler Gallery to track a pair of apparently antithetical organisational structures: on the one side, the “top-down structure” of the corporate world, on the other, the hierarchy free world of hacker culture.

On the corporate side, Denny is “focusing on case studies of three different existing formalised organisations – one is the GCHQ intelligence agency here in Britain, another is Zappos, the shoe sales company owned by Amazon, and the other is Apple.” All three have loosely ring-shaped headquarters, architectural models of which are present in the show, and the forms of which feed down into their graphic identities and function as metaphors for the free circulation of ideas within the companies.

For two of these organisations, Denny recreates elements of motivational presentations made within the company, both of which advocate the anti-hierarchical management system Holacracy, and a flexible, softened working environment that includes quiet spaces and playful elements. Both presentations deploy colourful cartoonish graphics that stylistically might be drawn straight from the pages of Diary of a Wimpy Kid. Such internal strategy data was only available about two of the organisations, since the third is notoriously shadowy, and closely guards all goings on at its spaceship-like headquarters: not GCHQ but Apple, of course, the Cupertino headquarters of which are shown as sleek, black and as impenetrable as its products.

While Zappos may be famous for its unconventional corporate structure, there’s something a little jarring about the thought of GCHQ employees chillaxing in a happiness-driven workspace and participating in a modish form of corporate philosophy that favours frontline (rather than top-down) decision making.

Can the corporate structure that suits a Nevada fashion retailer really be transferred to intelligence gathering and security? And does this parallel corporate navel-gazing suggest that it makes little difference within the company what the end product is – more suave slingbacks or slicker surveillance – just so long as contentment quotas are met?

While the corporate world endlessly self mythologises, less formal material is available relating to the history of hacker culture, which is explored through “twelve organisational moments around hardware” presented in vitrines designed for hard-drive stacks. The first of these dates back to the Tech Model Railroad Club of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, formed in the late 1940s. Its members used their experience in experimenting with model railroad systems and extremely complex networks of train switches in their approach to the earliest mainframe computers. “They used a lot of the strategies and gimmicks to develop computer software that was quite different from what more traditional researchers were doing,” explains artist and security researcher Matt Goerzen, who collaborated with Denny on the hacker-related material.

To formalise the hacker displays, Denny and Goerzen have created a series of what appear to be studious technical manuals relating to key themes within the history of hacking, to display alongside game-changing pieces of hardware repackaged as products – such as a Phone Phreak “blue box” sold on the Berkeley University campus by Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs as a way of getting free long-distance calls. At the Serpentine, the “blue box” is given Apple-style packaging, formalising this fruit of open technology as “in a way the first Apple product”.

Though this may all seems a bit fact heavy for an art exhibition, as with the internet itself, this surfeit of information makes it easier for the fiction to hide in plain sight. “If you only come out of the exhibition with one question,” says Denny, “that tension between what is fact and what is not isn’t a bad one.”

Products for Organising is at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery from this Wednesday until 14 Feb

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments