Bridget Riley: New Paintings, Wall Paintings, Gouaches

Bridget Riley has been creating abstract paintings for 50 years – and her latest work is as tantalising as ever, says Tom Lubbock

It is roughly 100 years since abstract painting started, and for some people it has had its day. In the middle of the 20th century it ruled the world. It was the inevitable and final state of art. But then, inevitably, it proved not so final. We could look at abstraction from the outside, and see it as something rather odd. Why this solemnity about shapes and colours? Why this obsession with purity?

But it isn't all over. It is nearly 50 years since Bridget Riley started painting abstract, and her allegiance to the revolution created by Kandinsky, Mondrian, Malevich and Rodchenko has never flagged or shown doubts. She has been one of the great renewers of abstraction. Since she first arrived with her eye-popping Op works, her painting has gone through several transformations. It's always been an impersonal art, but equally very open to emotions. And now you might think – Riley was born in 1931 – she is due for a "late style". Or is this it?

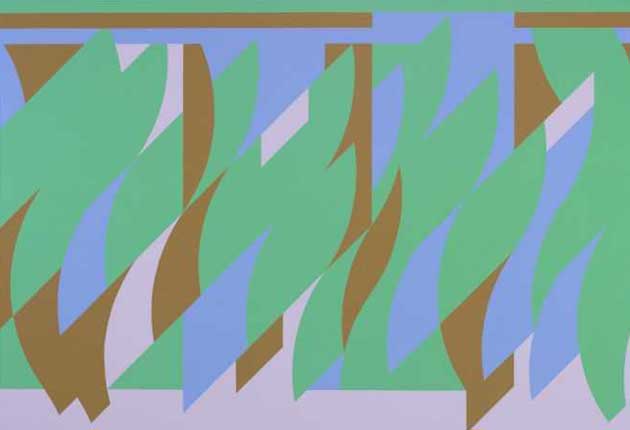

The recent wall paintings and paintings now showing at the Timothy Taylor Gallery are in the style she developed only about 10 years ago – "new curves" she calls it. (The previous curves were presumably the waves and ripples of the late 1970s.) But if these are "late" works, they don't have the remoteness and austerity that are sometimes associated with the term. The curves allow into her works an unprecedented flow of energy. The effect is almost youthful.

The two murals, for example, are boundless pieces. Though they have roughly a landscape format, and landscape colours too – blue, green, corn, pale orange - they break out of the picture's normal rectangle, to float as an irregular form on the surrounding wall. Their titles are Arcadia 2 and Arcadia 3. I'm never sure about Riley's titles. They're often so inventive and so beautiful, one's likely to give them too much weight. But in this case, Arcadia seems pretty straightforward. These fields of dancing forms aren't damagingly skewed by the thought of a rustic idyll.

Arcadia then – and not on the other hand Et in Arcadia Ego, that motto of mortality that's found in some 17th-century paintings. In those scenes, innocent shepherds stumble upon a skull or a tomb, inscribed with those warning words. Death too lurks among idylls.

Of course you'd never find that kind of title on a Riley; simply too much story would be implied. Riley has certainly drawn inspiration from the procedures of the old masters, but their stories have not been her interest. Still, this isn't just my whimsical word-play. In so far as Riley has any subjects, the subject of mortality is something you can meet in her art. You meet it in the form, or rather in the question, of limits. Where are the limits in her art?

In one way, Riley has been devoted to limitation – in her creative means. She quotes Stravinsky. "My freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. Whatever diminishes constraint, diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one's self of the chains that shackle the spirit."

Riley's constraint consists in the narrow repertoire of forms that characteristically she uses at any point in her work. Take the "new curves" pictures – and it's telling that she is happy to give them such a name. How many artists would be so self-conscious and explicit about a change of style? But Riley knows what she's doing, and declares it. The decision to introduce a new element, to alter the repertoire radically, is deliberate.

The elements of the "new curves" pictures are nameable, too. They are various types of sharp edge. There is no wobbliness, no blur. A picture is constructed out of curved edges – regular curves, compass drawn, swelling either to the left or the right – also verticals, horizontals, and diagonals that always slant to the right. These means are perspicuous and few. You can grasp them clearly as they intersect, pick up on one another, or form outlined shapes – almonds, thorns, kites, twisted ribbons.

But these edges are obviously not made by lines. They are created by the pictures' colours – again, only a handful of colours in each picture – colours that establish forms or seem to spread across them. You get the impression of planes interleaving, superimposed, transparent. And as you look, the structure complicates. At a certain point you start not to be able to follow it.

Ever since her first Op works, there's been a suspicion of tricksiness. It arises partly from the fact that her painting isn't at all physically expressive (therefore cerebral). The body, with its impulses and flukes, and the unpredictable and fluid substance of paint, aren't involved. Her materials are defined shapes. Their assembly is carefully controlled through a kind of collage. The paint is flat, and uniform, and latterly put on by assistants. It looks like a cool operation. Is it a kind of game?

There is certainly puzzlement, bafflement at work. The eye isn't being dazzled, as in the Op works, but it is being confused. It's caught in a battle between the graspable and the ungraspable. There are the recognisable, identifiable elements, and then there is the ensemble into which they are made, and in which they are increasingly inextricable. The forms interleave, go transparent, and they also align, echo, repeat, reverse. Keep looking and more and more of these relationships appear. You often wonder if Riley herself has got her eye on, and her mind round, all that's going on; whether she has seen and adjusted and approved every possible involvement.

At any rate, there comes a stage in the drama between elements and ensemble when ensemble simply wins. There's no point in trying to alternate your attention between the two. Literally you can keep an eye on the bounding curves and the shapes they make. They are perfectly clear when isolated. But the picture's object is to transcend them. And the moment you relax a strict focus, and let your eye stray, you're likely to be lost in an interplay so dense and multiplex that the elements just dissolve.

The meaning of Riley's paintings is not in what they depict (they depict nothing) or even in their associations (however much the colours and the titles of the Arcadia murals may suggest something outdoorsy). It's in the kind of experience she offers the eye. And in these pictures, she offers an experience of endlessness. It's brilliantly achieved. There are no containers or stopping places, and when there seem to be, they turn out to be decoys. Your attention scans and swims continuously, limitlessly.

We see so many artworks that can be consumed – and quite rightly consumed – in a couple of minutes that we should be grateful when some come along that ask for any amount of time. Endlessness is potentially endless. And yet I'm not sure that I believe in it, seductive though it is. With all the visual discipline of Riley's making, the vision is a kind of fantasy. It's not how the world goes. The shepherds suddenly bump into something. Their idyll is interrupted by a sense of limits. But these paintings, whether or not they may be called Arcadia, don't encounter or recognise any limits. They go on forever. It's strange to say that an abstract work is untrue, but so it is.

Bridget Riley: 'New Paintings, Wall Paintings, Gouaches' is at Timothy Taylor Gallery, London W1 (020 7409 3344) to 19 December (closed Monday), free

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies