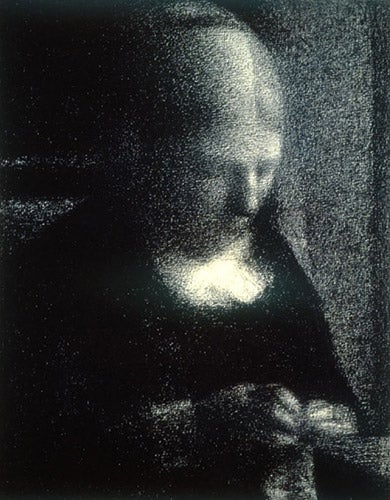

Great Works: Embroidery: The Artist's Mother (1882–83) Georges Seurat

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The word "painterly" is a piece of art-speak that doesn't always imply paint. The Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin coined the distinction between what he called linear and painterly art, in order to characterise – as he saw it – one of the big differences between the art of the Renaissance and the Baroque. It's a question of perception.

The linear is "the perception of the object by its tangible character, its outlines and surfaces". The artist dwells on the shapes and boundaries of things. The painterly, on the other hand, is "a perception by way of surrendering to mere visual appearance... The artist overlooks individual things, and observes the play of light and shade."

"In the former case, stress is laid on the edges of things; in the latter, the work tends to look without edges. Seeing according to volumes and outlines isolates objects, while for the painterly eye, they merge."

Linear against painterly, touching against seeing, outline against tone, objects against blur: such a distinction applies beyond the periods of the Renaissance and the Baroque, and they are more than perceptual terms too. They are psychological or conceptual categories. They are attitudes to the world. The linear is about control, clarity, grasping, defining. The painterly is about letting go, losing your focus and grip. There are linear paintings. There are painterly drawings.

Georges Seurat's Embroidery: The Artist's Mother is one the most extreme drawings ever executed – the least linear, grasping or defining. It holds back from any suggestion of contour. It performs entirely in tone. It has no interest in edges. It merges forms, blends solid into void. Like the face of a half moon on a misty night, the woman's head dissolves into the darkness behind her. Across her brow and cheek, shadows creep in the finest gradations. Her chin is lost in her chest. Her mouth is a formless blur. The figure very faintly fades into itself and its environment.

Seurat's transitions are seamless. In conté crayon, his grays graze the paper as lightly as ghosts. His drawing is an act of refraining. The miracle of Embroidery is that it doesn't look like the behaviour of a human hand at all.

But this picture involves grasp in another way. Notice its subject: it's a drawing about sewing. There's the artist's non-grasp, his drawing that loosens its grip upon the figure's forms. But there's also his mother's firm grasp, both manual and mental – her hold on her needlework, her attention to it. This comes through the blur, clear and strong. In fact, it comes through all the clearer for being so blurred. Seurat's drawing lets her withdraw out of its grasp and into her deep absorption. His unfocused handling emphasises how focused she is on her own handiwork.

Or is the picture's secret that his mother's work, and Seurat's, actually resemble one another? Both sewer and drawer are lost in an act of intense attention. In both, it's hard to tell the difference between active and passive.

Seurat's "surrendering to mere visual appearance" turns the artist into a super-sensitive instrument, who registers only nuances of light and shade. (The "painterly" is like the photographic). This requires disciplined self-control: it's also a form of automatism. In Embroidery, as in meditation, total concentration meets trance.

About the artist

Georges Seurat (1859-91) died of meningitis, aged 31. In his short life, he produced a whole career. His work was structured around a series of carefully plotted masterpieces: 'Bathers at Asnières', 'A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte', 'The Sideshow', and 'The Circus'. More than any other artist, his name has become identified with an ism – pointillism, or divisionism – painting by optical mixture, breaking colours down into dots of their constituent hues and letting them blend in the retina. Politically, this most orderly artist may have been an anarchist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments