Cash awards in the arts: Helen Marten should make it clear before the Turner Prize ceremony that the cash should be withdrawn from the prize

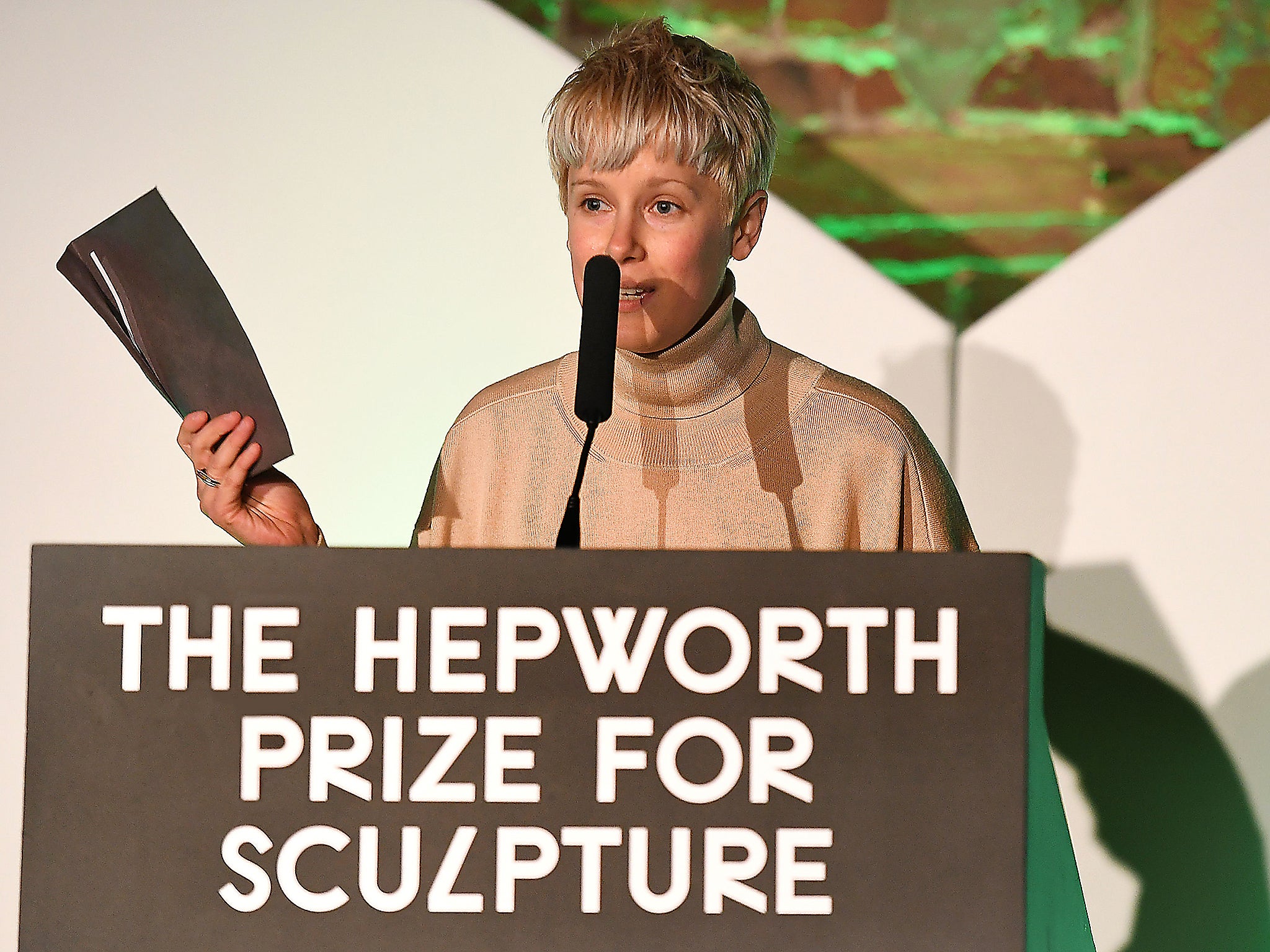

The winner of the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture has said she will share the £30,000 prize with all the nominees. Helen Marten is also up for the £25,000 Turner Prize next month. Why is it that some prizes in the arts have money attached and others do not?

The arts love prizes. There are literally hundreds of them, for writers, movie makers, artists, dancers, musicians. And many of them come with a decent amount of cash attached.

But now, the latest prize-winner has criticised the “hierarchical” nature of such prizes and pledged to share out the £30,000 award with her fellow nominees.

Helen Marten, winner of the first Hepworth Prize for Sculpture, says that “the hierarchical position of art prizes today is to a certain extent flawed. I would be very happy if they accept to share the prize among the four of us,” she told BBC Radio Four’s Front Row.

Indeed, after receiving the prize from Burberry head Christopher Bailey, she vented her existential angst about being on the winner’s podium at all. She said art was “deeply subjective”.

And she told BBC Radio 5 live: “We should not be asserting a hierarchy in saying this person is a winner above and beyond anybody else. The context of the world’s political landscape is changing so drastically. Amidst that, the art world has a responsibility to uphold an umbrella of egalitarianism and democracy and openness.”

As it happens, Marten is also up for the even-better-known £25,000 Turner Prize on 6 December. So she might have the chance to tell the world what she thinks of art prizes again. And with her generous approach to distributing the winner’s prize money, her fellow nominees must be hoping that if they don’t win, she does.

But I think that Marten should have gone much further in her remarks. She talked about the difficulties for artists about being in competition with one another, and she said she would share the prize money with the other shortlisted nominees. But she didn’t question the actual idea of cash awards. I do.

Why is it, for a start, that some prizes in the arts have money attached and others do not? The Turner, the Booker and many more come with a fat cheque – an astonishing £50,000 in the case of the Man Booker Prize for fiction. The Oscars, the Baftas, the Oliviers, the Evening Standard Theatre Awards and the Brit Awards are among those that have a trophy and usually a dinner, but no cash. It makes little sense.

Some will argue that the cash helps struggling artists, but internationally famous Booker Prize winners hardly come into that category. Look down the list of Turner and Booker winners and it stretches credibility to think of the likes of Hilary Mantel, Julian Barnes or Grayson Perry as struggling.

Besides, to anyone who makes that argument, I would refer them to a rather diverting passage in Stephen Fry’s autobiography. Talking about the excesses in London’s Groucho club in the nineties, he mentioned one fascinating incident.

He wrote of an evening in 1995 when Damien Hirst won the Turner Prize. Hirst arrived at the Groucho fresh from the Turner ceremony, put the £20,000 cheque behind the bar and said he wasn’t leaving until everyone present had joined him in drinking the entire winnings. That particular celebration of cutting-edge, contemporary art lasted until dawn.

Cash prizes in the arts generally do not go to help struggling young artists; they go to reasonably affluent, famous names who have had acclaimed exhibitions or well-reviewed, best-selling novels; the money can make the winners, as Marten indicated, a little embarrassed in front of their fellow nominees and fellow artists generally.

And, let’s be honest, the large sums of money come attached to a sponsor’s name and make the sponsor look philanthropic and devoted to the arts. I daresay that Burberry, Man Booker and other sponsors of such prizes do have a devotion to the arts, but a cash prize is quite an ostentatious way of showing it.

Many other industries, trades and professions have their share of prizes, but don’t see the need to have cheques attached. Journalism, for example, has its awards evenings, complete with dinners, heckling, roll throwing and generally questionable behaviour. But it doesn’t feel the necessity to shower money to the recipients. The honour of being recognised by one’s peers is sufficient reward.

So why is the honour of being recognised by one’s peers not considered sufficient reward is in the worlds of art and literature?

Let’s go back to Marten’s declaration of egalitarianism: “We should not be asserting a hierarchy in saying this person is a winner above and beyond anybody else. The context of the world's political landscape is changing so drastically. Amidst that, the art world has a responsibility to uphold an umbrella of egalitarianism and democracy and openness.”

Indeed. But egalitarianism extends beyond refusing to say that one artist is better than another. It should also mean egalitarianism among prizes, refusing to say that one prize is worthy of cash while another is not. Really, in the true interests of egalitarianism, Ms Marten should make it clear before the Turner Prize ceremony that the cash should be withdrawn from the prize. A prize set up to encourage discussion about contemporary art should not have become a prize that ends up in discussion about a fat sum of money and what the winner may or may not do with it.

Money as a prize creates dissension among artists, it serves for the greater glory of the sponsor, it dominates the headlines and detracts from discussion of the art form, and it defies logic in being attached to some prizes and not others.

If sponsors are determined to shower money around, then that is all well and good. Give the money to those art forms. Invest in museums, galleries, art acquisition, publishing houses. If they prefer, as of course they do, to sit on the top table at an awards ceremony and hand over a cheque in front of the TV cameras, then their motives are a little more questionable.

Prizes in the arts are beneficial. They draw attention to an art form and its practitioners and encourage discussion about that art form, encouraging visits to galleries, theatres, museums, bookshops, opera houses and cinemas. But all that will happen without the ostentatious presentation of a big, fat cheque and the questions that provokes. It’s time to celebrate the art but scrap the cash.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments