The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Copyright war: Street artists accuse big corporations of stealing their artworks

The family of the deceased artist Dash Snow have accused McDonald's of stealing Snow’s graffiti signature to decorate the walls of hundreds of their restaurants – and his case is not the only one

Fast food giant McDonald’s has its own, very recognisable logo, but it may soon need to defend itself against a copyright lawsuit for allegedly appropriating someone else’s, in this instance the stylised name of a street artist.

The family of the deceased artist Dash Snow recently brought the case to a Californian court. Also seeking to protect Snow’s anti-consumerist reputation, they claim that McDonald’s has committed copyright infringement by using a “brazen copy” of Snow’s graffiti signature and featuring it on the walls of hundreds of its restaurants. Snow started his career as a graffiti artist with the crew IRAK.

This is just the latest in a string of cases where graffiti or street artists have brought copyright suits against corporations that have allegedly copied their pieces, including fashion companies Moschino and Cavalli, and clothing retailer American Eagle Outfitters. These cases were all settled out of court.

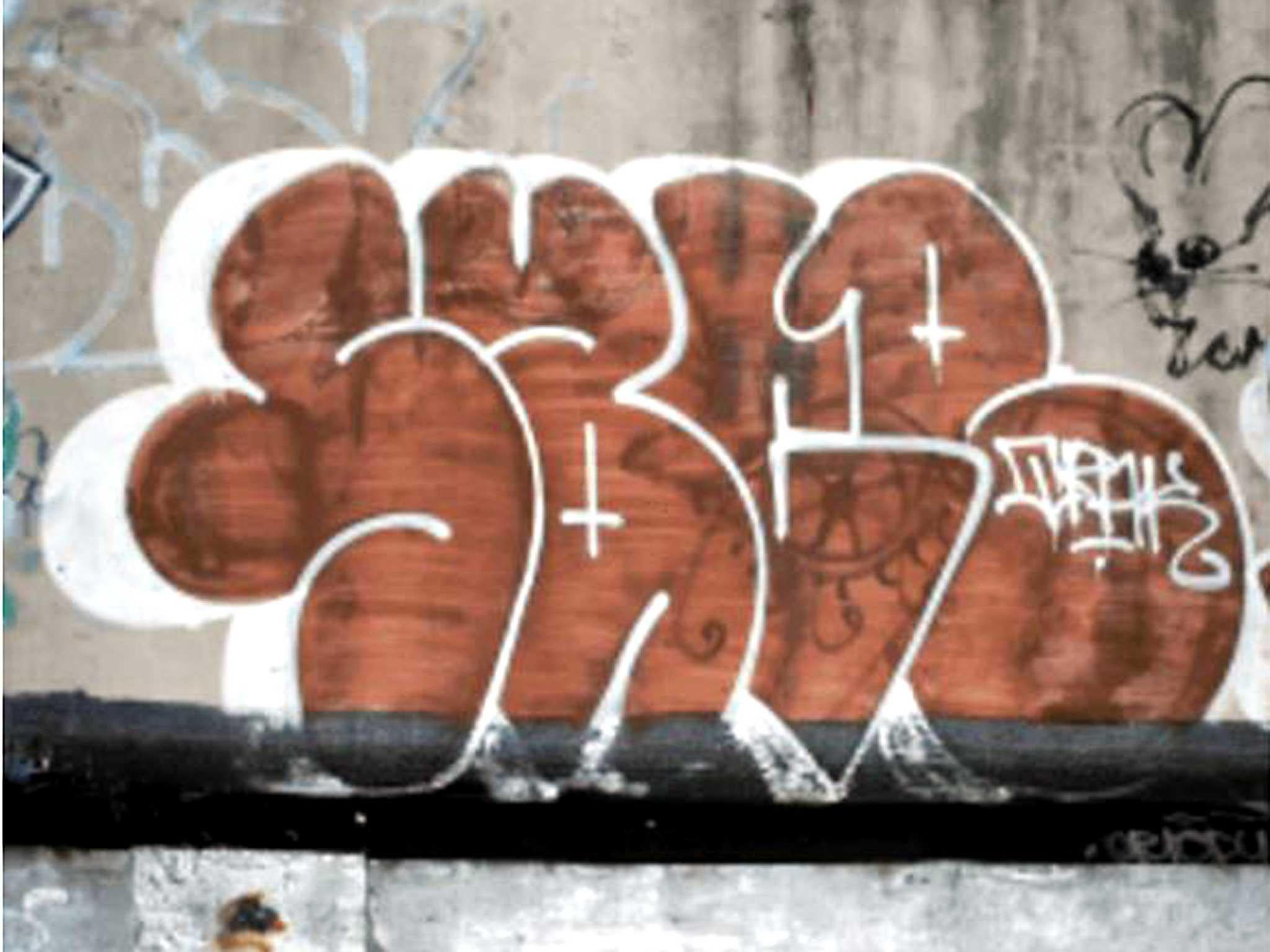

Yet the Dash Snow dispute is the first that seeks copyright protection of what within the graffiti subculture is called a throw-up. A stylistic signature representing the artist’s name, the throw-up is made of personalised (often bubble) letters, outlined in one colour and filled with another. Another, less sophisticated type of graffiti signature is the widely known “tag”, which consists of letters drawn in condensed calligraphic form. Both populate urban environments around the globe.

Throw-ups and tags represent a strong desire to be recognised and appreciated within the subculture. They are basically street logos. They glorify identity and are mainly addressed to other graffiti artists within the community – often representing the first step in the career of what may eventually become a street artist.

But some may argue that throw-ups and tags lack a sufficient level of originality to be considered copyrightable, and are too trivial to attract protection.

Yet the debate about whether these street logos deserve such protection may be influenced by the fact that they are frequently perceived negatively by large sectors of society, as opposed to more elaborate pieces of street art, which are increasingly accepted and appreciated.

Often considered to be mere scrawlings, which visually pollute our cities and require expensive cleaning by local councils, throw-ups and tags are also disliked by many because they are ubiquitous, sometimes associated with gangsterism, and (to the eyes of people outside the subculture) indecipherable. Such a belief is reinforced by the assumption that throw-ups and tags seem easy to paint, or are the product of mischievousness rather than artistic ability.

But all this ignores the fact that over the years, most graffiti artists develop and perfect their own lettering style. Even throw-ups and tags which to an untrained eye seem banal and meaningless may be considered creative and sufficiently original within the subculture.

Graffiti has historically been an art movement that revolves around letter formation and calligraphy. Over the decades many original ways of drawing letters, and adorning them by adding arrows, crowns, curves, twists and other decorative elements, have been created and consolidated. And new lettering styles that seek to re-interpret, reconstruct and deconstruct the alphabet are still regularly created within graffiti communities.

That many tags may be considered original and therefore protectable by copyright is confirmed by the high level of competition between artists, who aim to distinguish their own lettering style from that of others. Accusations of copying throw-up and tag styles (what in graffiti jargon is defined as biting) are not uncommon within the graffiti scene. This indirectly confirms that more original letters, such as the ones developed by Dash Snow, are the result of creative effort.

Take, for example, the famous Banksy tag. One may arguably claim it is unique, and therefore eligible for copyright protection. The upright back of the capital letter “B” is missing; the letter “k” needs the “n” for a support; the top of the letter “s” is slightly cut off and the final “y” looks semi-dwarf. Tags are clearly far from simply written words – they are also images.

Throw-ups and tags have undeniably grown in popularity and have attracted attention from marketing gurus always in search of new ideas capable of infusing street credibility into their commercial offers and making products more edgy and marketable. There have also been cases of street art falsely attributed to the real artist. And a variety of graffiti font styles are regularly offered for sale online for creative people and professionals to use in their urban artworks.

The belief that innovative lettering styles can be original enough to attract copyright protection is reinforced by the general principle enshrined in most copyright laws around the world that the quality of a work is not relevant for the purposes of copyright subsistence. In other words, copyright protects both highly meritorious and (what many people may consider) awful works. The concept of artistic work has become quite a broad one nowadays.

In the end, if copyright laws consider simple charts, diagrams and technical drawings as copyrightable (as they do in most jurisdictions), it doesn’t seem so heretic to give stylish and original graffiti lettering the same treatment.

Enrico Bonadio is senior lecturer in law at City, University of London. This article was originally published on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments