The great exhibition of China: Scrolling back the centuries with 1,200 years of Chinese painting

As the V&A unveils an exhibition of 1,200 years of painting in China, curator Hongxing Zhang offers tips on how to view it

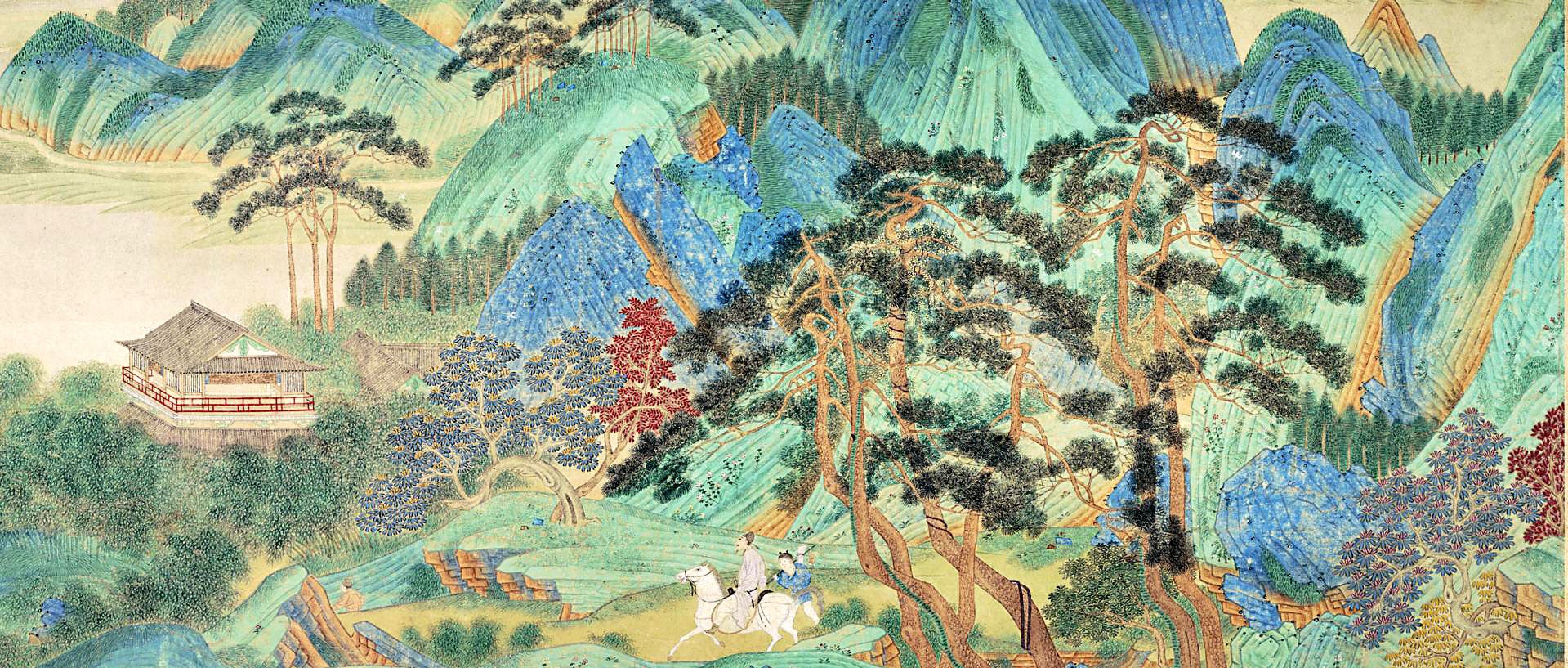

You can’t fault the V&A for ambition when it comes to its latest blockbuster show: spanning 1,200 years, Masterpieces of Chinese Painting: 700-1900 celebrates one of the world’s oldest artistic traditions via a display of more than 100 works on silk and paper, many exceptionally fragile, that has taken curator Hongxing Zhang years to gather.

It’s a remarkable undertaking and the effort does not stop there: for much of the exhibition’s fascination lies in a complex visual language that will be unfamiliar to many visitors. But in order to decipher this, help is at hand. Below Zhang offers his point-by-point guide on how to look at Chinese painting:

Look from right to left

Many of the works in the exhibition take the form of painted handscrolls, which, as with Chinese text, were intended to be read from right from left. The origins of the handscroll stretch back to the second century and over the next few centuries a combined text-and-picture tradition developed.

Taking advantage of the scroll’s horizontal format, painters experimented with spatial and temporal progression, presenting scenes in a continuous sequence. From the 11th century onwards, they used this not only to illustrate narratives from classical poetry and Buddhist or Confucian tales, but also to create fluent landscapes or genre scenes designed to provide imaginary travelling experiences.

The joy of the scroll as a mode of visual storytelling lies in the fact that the viewer can control the pace at which they proceed and move back and forth between scenes. In this way, it is a far freer experience than watching a film or a play.

Scrutinise the calligraphy as closely as the painting

Calligraphy, or writing as fine art, was revered as a visual art form long before painting. From the 12th century, during the Song dynasty, it was regarded as integral to the painter’s practice; training in the five major calligraphic styles (seal, clerical, regular, running and cursive) formed part of an artist’s basic education.

Inscriptions could bring a number of extra dimensions to a work. For example, Song dynasty emperor Huizong’s writing to the left of his painting Auspicious Cranes both allows him to show off his “slender golden” style (a fine script with thin lines) and relate precisely how the painting came to be made: moved by the sudden appearance of 20 Manchurian cranes in the sky above the Forbidden City, he painted the phenomenon as a good omen for his reign.

Count the seals

You can learn much from the numerous seal marks imprinted on paintings over many centuries, most notably their provenance. Seals were used by collectors to mark their ownership of paintings, even before artists began to use them as a form of signature, as the artist acquired a higher status.

Particularly striking are the sets of seals used by emperors from the 12th century onwards. For instance, Emperor Huizong typically marked his handscroll painting collections with seven seals, four at the corners of the painting surface and the remaining three on the mount – a pattern followed some years later by Jin dynasty emperor Zhangzong, whose seals can be seen on the scroll Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk and who greatly admired Huizong, despite being from the dynasty that overthrew him.

Meanwhile, the 18th-century emperor Qianlong normally used five seals for his painting collection, but there are also many examples where the number is greater, especially when he had inscribed his own poems on a work.

Look while you can!

Chinese paintings were not intended for display over long periods and owing to their production on silk or paper, tend to be fragile. Typically, a Chinese scroll painting would be stored rolled up in a box, and put on view only for short periods at a time. It would certainly never have been intended to be seen in a gallery.

Owners would derive maximum enjoyment from rotating their paintings, which also minimised damage from sunlight, grease and dust. Displays would also be changed according to the season, so as to indicate the time of year and the various calendar festivals. In the 17th century, during the height of connoisseurship, some collectors even tried to develop a formula for the rotation of paintings.

Because of their fragility, many works in the show are exhibited a maximum of once every five years and some have never been seen in Europe. One such revelation is the delightful 15th-century Court Ladies in the Inner Palace which depicts women in the imperial palace playing sports, including games resembling golf and football, before the custom of foot-binding put a stop to such activities.

And do keep an eye out for western influences…

…in the latter rooms of the exhibition, that is. From the 18th century to the beginning of the 20th, during the Qing dynasty, the influence of the West on artistic practice became increasingly apparent. With the influx of Jesuit missionary-artists, Chinese court painters learnt the laws of linear perspective and chiaroscuro. They were further inspired, both in techniques and subject matter, by the imported prints and illustrated books that flowed in from Europe following the development of trade links.

To take two examples from the works on display, the longest scroll in the exhibition, at 14 metres, Suzhou Prosperity by Xu Yang, noticeably draws on a Western use of perspective to depict urban life inside the city walls receding into the far distance. Meanwhile, Portrait of Gao Yongzhi as a Calligraphy Beggar, an 1887 work by the Shanghai painter Ren Yi, features the first example in Chinese painting of an eye depicted naturalistically.

‘Masterpieces of Chinese Paintings: 700-1900’ is at the V&A until 19 January 2014. Full information at vam.ac.uk/masterpieces

Chinese timeline: the key dynasties 700-1900

Tang Dynasty, 618-907

The Tang Dynasty saw China become the richest and most powerful country in the world. Centuries later, Chinese artists would still compare their work to that of the Tang Dynasty. Viewed as the classical period of Chinese art, Tang Dynasty paintings were primarily bright-coloured Buddhist works on silk banners and screens.

Song Dynasty, 960-1279

Many characteristics of modern China, such as a booming population and the staple foods of rice and tea, first emerged during this time. Calligraphy was venerated as a prime artistic skill, and the period also saw the rise of stunningly detailed monochrome landscapes featuring plants, animals and fishermen.

Yuan Dynasty, 1279-1368

For the first time in its history China came under foreign rule, that of the Mongol Empire. Artists used landscape painting as a means of self-expression, producing scenes reflecting the solitude they experienced under the oppressive Mongol occupation.

Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644

The re-establishment of Chinese governance under the Ming Dynasty saw a prolonged period of cultural restoration. Art gained a new prominence in public life with large, decorative and colourful pieces becoming popular. Calligraphy and brushwork emulated earlier Song and Yuan styles, with a nostalgic take on the previous periods.

Qing Dynasty, 1644-1911

The nomadic Manchu tribe overthrew the Mings to set up the Qing Dynasty and extend its reach into Central Asia. Art mainly revolved around traditionalists re-imagining older styles, although towards the end of the dynasty’s rule, the influence of Western styles began to become apparent.

Ralph Blackburn

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies