When the fascists tried to tame the modern masters

The news of a €1bn hoard of paintings found in Munich is a reminder of Hitler's hatred of great art

Such are the problems and complexities of the issues surrounding the aftermath of the Nazi-era purging of so called "degenerate art" – which means art made, owned, or subject to the nefarious influence of the Jews, Jewishness and all that such labelling came to mean – that it is not at all surprising that it has taken nearly two years for the Bavarian authorities to make public the extraordinary seizure of almost 1,500 artworks from the apartment of Cornelius Gurlitt, the 80-year-old son of a German art historian once in the pay of Joseph Goebbels.

The value of the cache seized from this filthy, overloaded apartment in Munich is said to be in the region of €1bn, yet that could easily be a wild underestimation, given the importance to the history of 20th-century art of some of the artists whose works have already been named and identified – Chagall, Kokoschka, Franz Marc, Kandinsky, Klee, Picasso, Emil Nolde, Beckmann, Matisse, Kirchner, Liebermann. It is a roll call of key figures.

Why was this art vilified by the Nazis anyway? Degenerate art was said by Hitler (who was himself a mediocre dauber of Romantic scenes) to be "anti-German". A key exhibition of this so called degenerate art was held in Munich in 1937, but this was only the latest among many; in fact, art was being stolen from Jewish owners, labelled as subject to the wicked and emasculating influence of the Jews, and exhibited as degenerate from 1933 onwards, the year that Hitler came to power.

In that same year the Bauhaus, which had been forced to re-locate from Dessau to Berlin, was forced to close because it was said to be a breeding ground for "cultural Bolshevism", and in 1934 Hitler thundered against degenerate art in a speech delivered at Nuremberg. In 1935, an official decree put all exhibitions, whether public or private, under the direction of the Reichskunstkammer. Hitler's speeches and the writings of Alfred Rosenberg made rabble-rousing, pseudo-academic links between artistic production, politics and crude racial theorising.

Much rhetoric was spilled about blood, soil and Nordic supremacy. Goebbels called for a "racially conscious" popular art, adding, also in 1935, these chilling words: "The freedom of artistic creation must keep within the limits prescribed, not by any artistic idea, but by the political idea." Artists and their works were threatened as never before by legal action at the behest of the state. There was nowhere that privacy, inwardness, the personal impulse, the right to dream, could hide their heads.

An official, state-directed, state- governed art came into being, as sterile, monumental and self-aggrandising as it was academic. Collectors were robbed or blackmailed, works burnt. Teachers such as Paul Klee were dismissed from their teaching posts. Entire movements – Modernism, Cubism, post-impressionism – were mocked and vilified.

Galleries and entire collections were stripped of their paintings – it is said that about 16,500 works were seized, many of which disappeared, never to re-appear. Some – as we see today – are still emerging from unexpected crannies. Yet others passed through the hands of auctioneers in Lucerne. Many went abroad. Heaps of them were burnt in Berlin. And, as the years passed by, the persecution of Jews – cultural and physical – gathered momentum, focus and ferocity. The moment of the destruction of mere canvases was succeeded by the wholesale destruction of their makers and their sympathisers. Savonarola was among us once again.

The mockery, denunciation and persecution reached their climax in 1937, when a show of "entartete kunst" went on display in the frivolous arcades of the Hofgarten in Munich. Simultaneously, and as if to teach artists and onlookers alike the correct way of doing things, an exhibition of the officially approved German art went on show at the new House of German Art in that same city.

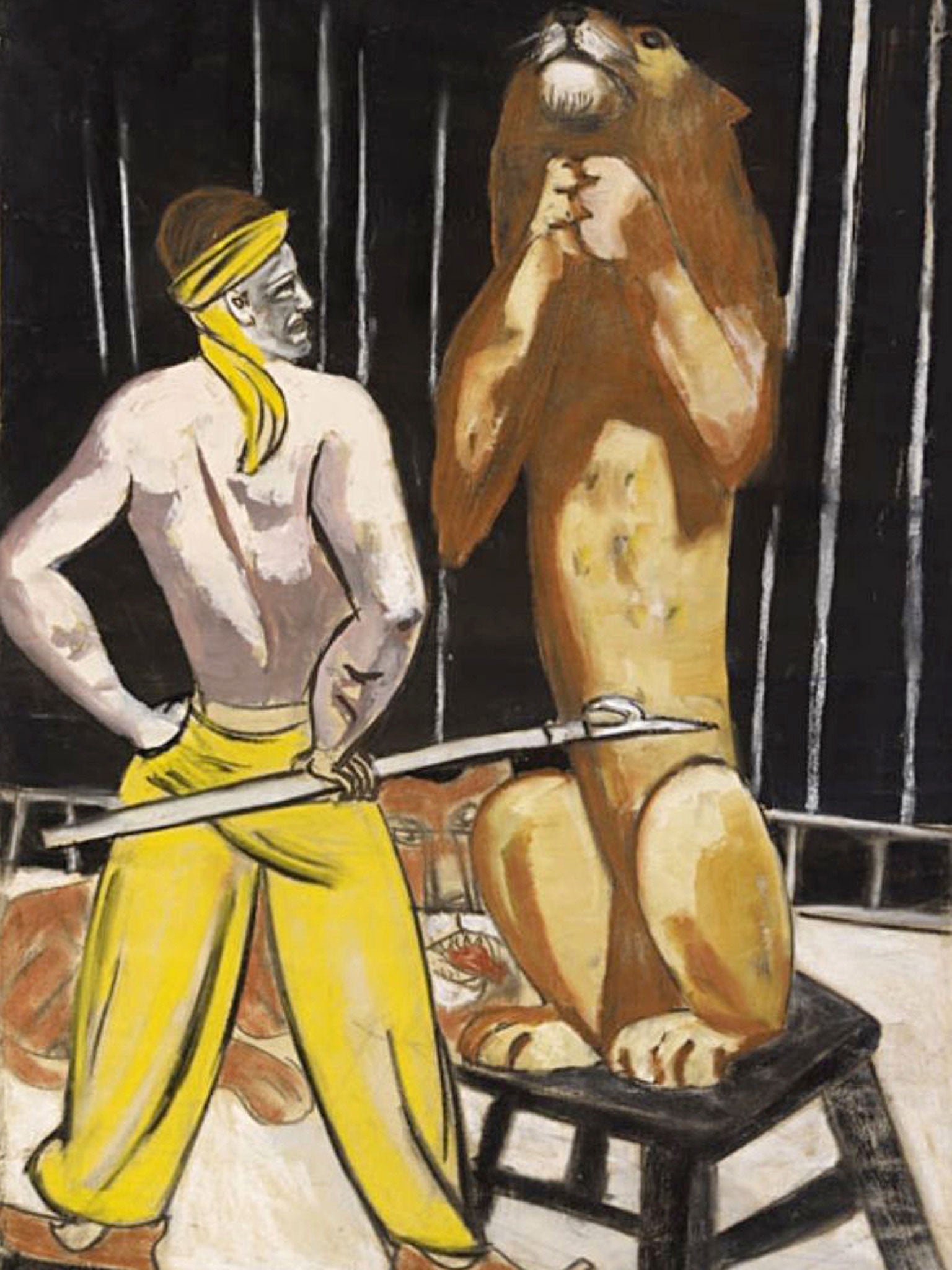

What exactly did degenerate mean though? True German art was to be a celebration of bodily perfection and racial purity. It was an art around which society could come together. It was not complicated by subjectivity. It was not slippery in its meanings. By contrast, degenerate art was a hole-in-corner affair, mired in the personal and the morbidly introspective. It involved a modicum of tortured and unhealthy mirror-gazing. Bodily forms were often wildly distorted – it is almost as if these so called degenerate artists were bent on cocking a snook at the idea of bodily perfection.

By contrast, the new art would never pose a covert or overt threat to the new body politic because it would be the idealised embodiment of that body politic. And so an entire swathe of society was rubbed out, from curators to collectors. Dealers and other art professionals were threatened and dispossessed – or obliged to recant. Such a one was the father of Cornelius Gurlitt, who had once been a respectable art historian. But why did he still have so much in his possession for his son to hoard? Was he, after all, playing a dangerous double game?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies