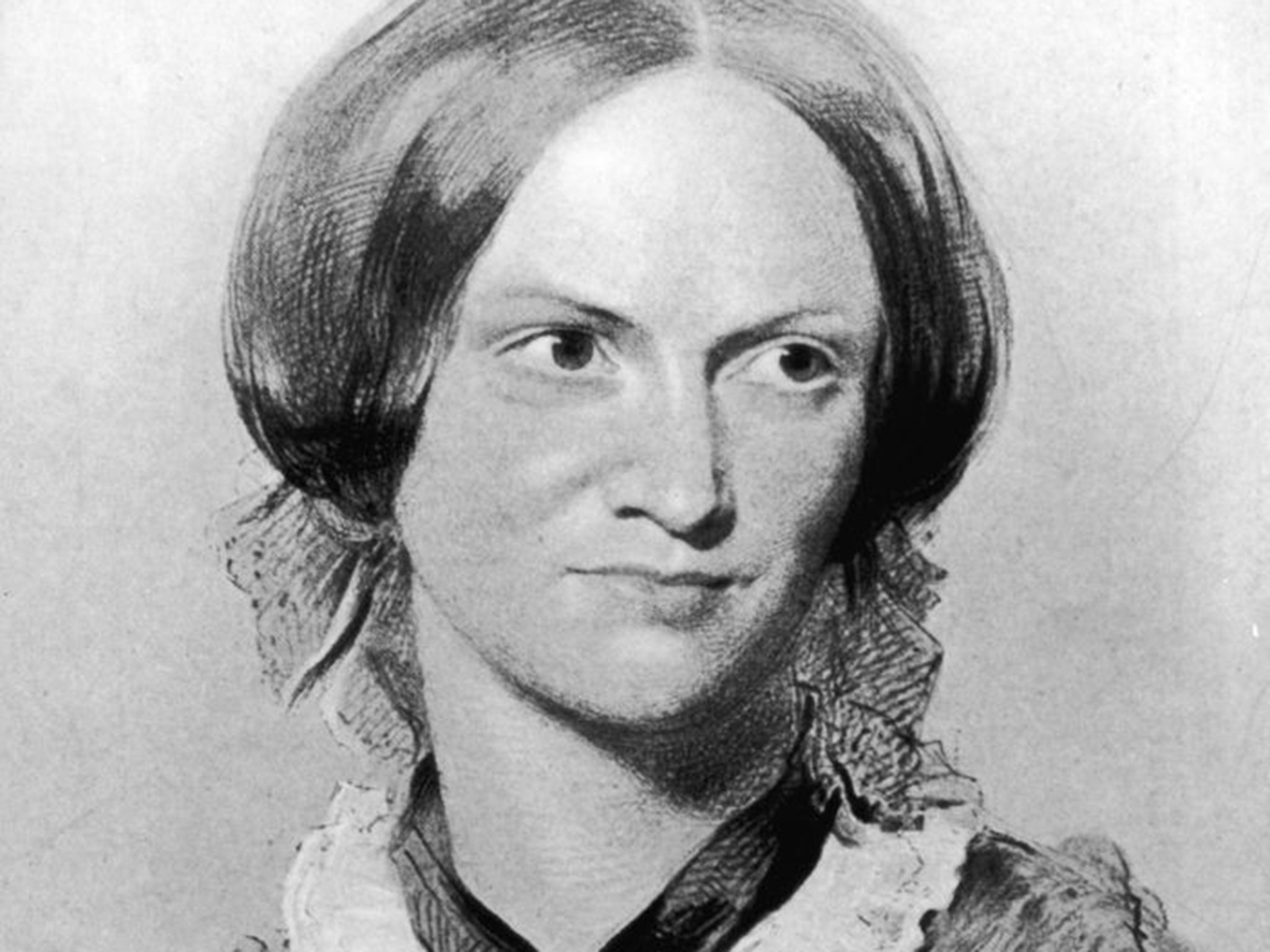

Author Charlotte Brontë was an uncompromising feminist trailblazer

With her bicentenary approaching, Claire Harman, the author of a long-awaited new biography, explains what the novelist and her heroines can still teach us

As a poor, plain parson's daughter, struggling to make a living as a teacher and governess, Charlotte Brontë didn't think of herself as a potential revolutionary, but as soon as she started to express herself, revolutionary views came out. She wrote Jane Eyre in secret and published it under a pseudonym, so had little idea of what a sensation it was causing among its first readers, who were bowled over by the novel's freshness, passion and brilliant storytelling.

But most of all, it was the novel's heroine who made people sit up and take notice, with her fiery spirit and refusal to compromise. "Unjust! Unjust!" the 10-year old Jane declares when she faces up to her cold-hearted relations and turns on them "like any other rebel slave". Alarm bells rang in the ears of the critics, even while they gobbled up the gothic thrills of the story and rushed towards Jane's happy ending with Rochester. What was all this about equality, about insubordination, this denunciation of clerics as hypocrites and authority figures as questionable? One outraged reviewer claimed that the novel embodied exactly the same spirit as was stalking Europe in the form of revolution, while another accused the author of a perilous "moral Jacobinism".

Culture news in pictures

Show all 33You'd think 168 years would be long enough for the culture to have absorbed what an obscure Victorian girl had to say, but when I reread Brontë's novels recently, I was struck by how much in them remains totally undigested. Jane Eyre has been, in some respects, the victim of its own success: in print ever since 1847, read by millions, made into films, plays (one is showing at the National Theatre right now), sequels, prequels – it is a national treasure, as familiar and comforting as a box of chocolates. And like all classic books, people feel they know all about it without necessarily having to look at a single page.

Everyone remembers the scenes where Jane denounces her cruel aunt, Reed, defies the bullying teachers of Lowood and proudly refuses Rochester's shoddy compromise plan to make her his mistress. But the stringent principles underlying the drama have lost some of their visibility. "I am no bird, and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will" is a statement as bracing as any in Karl Marx's revolutionary manifesto, published the year after Jane Eyre: Brontë's girl rebel speaks for all trampled people when she decides to speak up for herself, and is amazed at "the strangest sense of freedom" that comes immediately in its wake – "it seemed as if an invisible bond had burst".

The inequality that Charlotte experienced most sharply was that of the sexes, brought home, literally, by the different treatment meted out to herself and her brother Branwell. He was given educational opportunities denied to his brilliant sisters and his desire to be an artist was encouraged, while the girls had to think primarily of earning money. Charlotte hated being a teacher and governess, but stuck to it doggedly, hoping to escape through writing. But the irony was not lost on her that whether they worked or not, women were never at liberty, while their brothers were habitually let loose in the world "as if they of all beings were the wisest and the least liable to be led astray".

Marriage was not a way out; she said she'd do anything other than make a pragmatic or mercenary match. Charlotte approved of "action" anyway and believed that even wealthy girls should be brought up to be independent so they could avoid the shallow and "piteously degrading" marriage market. Her heroine, Shirley, in the 1849 novel of that name embodies the freedom that an independent mind (and independent means) can give. Wealthy, handsome, healthy, carefree, she's by far the most active and least anxious of all Charlotte's female characters, if also the most unusual. "Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do."

Jane Eyre's statement seems so reasonable, but even with suffrage, the pill, equal-pay legislation and new men, we've hardly begun to get to grips with her feminism. One of the most surprising scenes in Jane Eyre is one that might have been presented as a sort of idyll, when Jane is taken shopping by Rochester in preparation for their wedding, in the brief period between him declaring his love and her finding out about his wife. Jane is happier than she ever imagined possible, but her conscience never sleeps, and "the more he bought me, the more my cheek burned with a sense of annoyance and degradation". That word again, "degradation"; not one usually associated with shopping-trip scenes (think of it trying to find a place in Pretty Woman, or Keeping Up with the Kardashians), but the only thing that makes it possible for Jane to accept any gifts from her bridegroom-to-be is her private determination to pay every penny back at a later date, using her own earnings. It's hardcore, and it hurts.

Charlotte stood by her belief that inherent worth would be clear to the right observer, though her most unfortunate heroine, Lucy Snowe in Villette, finds it hard to believe that anyone will ever see past her plainness and has developed "a haunting dread of what might be the degree of my outward deficiency. . . a great fear of displeasing". Charlotte told her first biographer, Elizabeth Gaskell, that she had disagreed with her sisters Emily and Anne when they argued that heroines of novels always had to be beautiful and before setting out to write Jane Eyre said "I will show you a heroine as plain and as small as myself, who shall be as interesting as any of yours". It was a bold decision, and one that casting directors can never quite bring themselves to follow, but a lot of the power of the book comes from the fact that it is no simple Cinderella story; Jane's looks are one of her many misfortunes.

When Jane wants to arm herself against the folly of first thinking Rochester might love her, she sits down in front of the mirror and makes a ruthlessly realistic self-portrait, "without softening one defect" and writes underneath it "portrait of a Governess, disconnected, poor and plain", to hammer home the truth of her situation. She makes a sort of dark selfie, in other words, to quell her vanity. Long before Freud, Charlotte understood how female narcissism was the besetting sin that keeps women down, but she has the antidote: self-esteem.

There's much to be learnt from these revolutionary sentiments. When Charlotte was on the brink of beginning Jane Eyre, she wrote to her friend Ellen about how much she would like the power "to infuse into the souls of the persecuted a little of the quiet strength of pride". How horrified she would have been at an age which thinks lap-dancing can be empowering, or sexting a product of enlightenment. "Because I'm worth it" meant something different to Jane Eyre.

Coming up for Eyre

Surely only Hamlet can surpass Jane Eyre for its sheer number of film adaptations. And with each version comes a new interpretation of the independent Jane. The first of eight silent film accounts arrived in 1910 – before one with sound appeared in 1934, featuring Virginia Bruce as a Jane with kohl-rimmed eyes.

Considered a seminal reworking, the 1943 version starred Orson Welles as Rochester, but feminists won't take kindly to Joan Fontaine's damsel-in-distress portrayal of plain Jane. The same year saw Jacques Tourneur's horror film I Walked With a Zombie, which transposed the story to the modern-day Caribbean, where the mad wife becomes a victim of voodoo.

At 31, Susannah York was considered too old to play the 18-year-old in 1970. She was also thought too beautiful, but she still delivered a strong-willed Jane.

Charlotte Gainsbourg played Jane prim and reserved in Franco Zeffirelli's 1996 film – which was also notable for the complete lack of sexual chemistry between Gainsbourg and William Hurt's Rochester – while Samantha Morton impressed the following year with a calm but inwardly passionate portrayal.

Critics agreed that Mia Wasikowska gave a strong performance in the 2011 film, neatly expressing Jane's repressed emotions with a glance.

In addition to these, the novel has inspired three musicals, two operas, two ballets and an orchestral symphony. Expect many more.

'Charlotte Brontë: A Life’ by Claire Harman (£25, Viking) is out now

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies