Best history books for Christmas

A recession in history? In British universities, it feels like it. Deep cuts and job losses appear on the horizon, or are already happening. Whoever is in government, harsh conditions are probably ahead for history in the academic world.

Publishers, meanwhile, lament that these are hard times too for serious, commercially viable non-fiction, and likely to become harder. University presses, with their own arcane pecking order, also often fear for their futures. It seems as though the boom in TV historical documentary and docudrama may be starting to decline. One might even begin to envy history's far higher profile in some other countries, despite all the bad-tempered quarrels or political interference accompanying that.

Still, if there are dark clouds on the horizon, one would barely register that from the astonishing profusion of new history titles in 2009. History remains almost the only sort of intelligent non-fiction regularly to enter the bestseller lists. And this can happen with little if any sign of dumbing-down, or of the divorce between academic specialists and a broader public.

British-born or based historians are almost uniquely global, with a . major presence in Europe and beyond. Given our national tendency to monolingualism, this is as remarkable as it is heartening. Fine examples were numerous in 2009. Dominic Lieven crowns his long immersion in the history of imperial Russia with Russia Against Napoleon (Allen Lane, £30), brilliantly recovering the titanic struggle for Europe from 1807 to 1814 and centring on the extraordinary story of Napoleon's 1812 venture to Moscow and back. More recent Russian history is intertwined, in the work of many scholars, with that of Communism and world revolution. Archie Brown, in The Rise and Fall of Communism (Bodley Head, £25), though effectively covering the globe (albeit maybe comparatively a bit thin on China), focuses on the Russian experience. His conclusions neatly balance the equally pertinent questions of why Communist systems collapsed, and why they lasted so long.

Trotsky, the Bolshevik most powerfully associated with persisting hopes of global transformation, has had many biographers including the classic trilogy by Isaac Deutscher. Robert Service, less admiring by far, has uncovered a mass of new information, some of which makes for a pretty unattractive view of the man. Trotsky: A Biography (Macmillan, £25) is sparkling on his political and personal travails, and indeed his crimes and follies. Its main shortcoming is the scant attention it gives to the political theorist. It follows that Service is scornful of the latterday enthusiasts who still call themselves Trotskyists. No wonder they almost all seem to hate the book.

One place where the idea of revolution seems very much alive is Iran. Homa Katouzian's The Persians: Ancient, Medieval and Modern Iran (Yale, £30) is neither elegant nor especially original, and drifts repeatedly into an anecdotal and boastful style in detailing Iranian achievements. But it is maybe the broadest and best overview available in English of a country which we need urgently to understand better. It should be required holiday reading in the Foreign Office, and maybe the White House too.

Looking further back, Peter H Wilson tackles a mighty theme which has, in English at least, been amazingly neglected: the 17th-century Thirty Years War. Europe's Tragedy (Allen Lane, £35) is suitably massive, almost encyclopaedic, in scope. Although Wilson is concerned to debunk some of more apocalyptic claims about the war's long-term effects, he still shows that this was probably the most terrible period in European history between the Black Death and Hitler.

British – and American – historians continue to write British history too. Few are more inventive than Yale's Steve Pincus. His 1688: The First Modern Revolution (Yale, £28) shows dazzlingly that what was once celebrated or indeed mocked as the "Glorious Revolution" was far more violent, more complex, more transformative – more a real revolution, in short – than we had usually thought. Keith Thomas, in The Ends of Life: Roads to Fulfilment in Early Modern England (Oxford, £20), explores how our ancestors thought about "the good life": what aims people should pursue, in what balance between pleasure and morality, honour and faith, duty and self-discovery. His survey extends from the early 16th to the late 18th centuries.

My own Bristol University colleague Ronald Hutton continues his engagement with the history of modern paganism in Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain (Yale £30). It's not so much about ancient Druids themselves as the multiple modern uses, abuses, fantasies and revivals of the idea of Druidism.

Broad overviews of modern British history have proliferated, including major recent offerings from Brian Harrison (Seeking a Role: the United Kingdom 1951-1970; Oxford, £30), David Kynaston (Family Britain 1951-1957; Bloomsbury, £25), Richard Vinen (Thatcher's Britain; Simon & Schuster, £20) and the BBC's Andrew Marr (The Making of Modern Britain; Macmillan, £25). The most intellectually substantial of these is Harrison's; the slightest but surely most entertaining is Francis Wheen's Strange Days Indeed (Fourth Estate, £18.99), his often jolly but oddly disturbing gallop through the Seventies.

Wheen deftly mingles light and shade, a certain irresistible nostalgia with an insistence that this was truly a strange, shadowed decade, and one where paranoia seemed both ubiquitous and often all too justified.

Then, of course, there's the kind of history that aspires to the global. Christian Wolmar has long been known as the best-informed expert and deadliest critic of Britain's farcically ill-run railway system. Now, in Blood, Iron and Gold: How the Railways Transformed the World (Atlantic, £25), he reveals some of the passions behind all that, and his immense knowledge of how the iron horse has shaped world history since its first invention.

John Darwin's The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World System, 1830-1970 (Cambridge, £25) is surely now the finest, and will be the most influential, general survey of British imperial history. Jordan Goodman, in The Devil and Mr Casement: A Crime Against Humanity (Verso, £17.99), explores one of the earliest great modern human-rights campaigns: Roger Casement's crusade against exploitation and near-genocide in the Putumayo between Colombia and Peru.

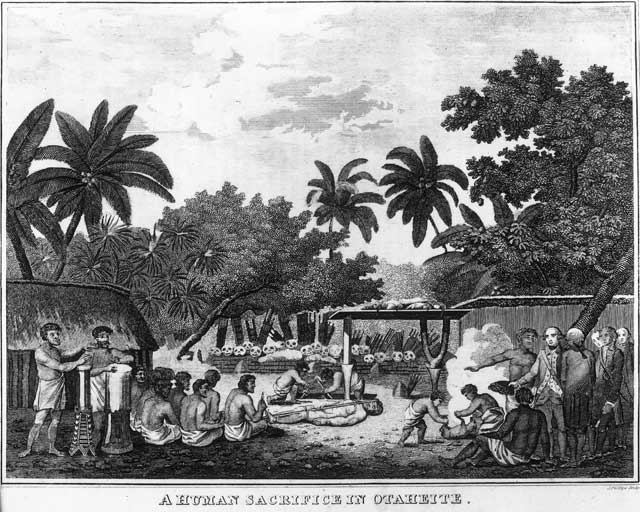

From continents and superpowers to small islands: Europe's and America's encounter with Tahiti was a very minor episode in the vast saga of imperial exploration, conquest and culture-clash. Yet it generated a profusion of myths and an enduring romantic fascination with the island and its people.

Anne Salmond's Aphrodite's Island: The European Discovery of Tahiti (California, £20.95) looks afresh at these, but also, more innovatively, probes the stories and legends the islanders themselves wove around those early encounters. James Cook and other early explorers took it for granted that they were the ones with power, in control of all those cross-cultural transactions. Yet as Salmond shows, Tahitians were equally convinced that they were writing the script, the Europeans responding to their calls. The resulting entanglements had consequences sometimes grotesque, often tragic.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks