Bouchercon, the World Mystery Convention: Why crime thrillers are still popular, despite crime levels going down

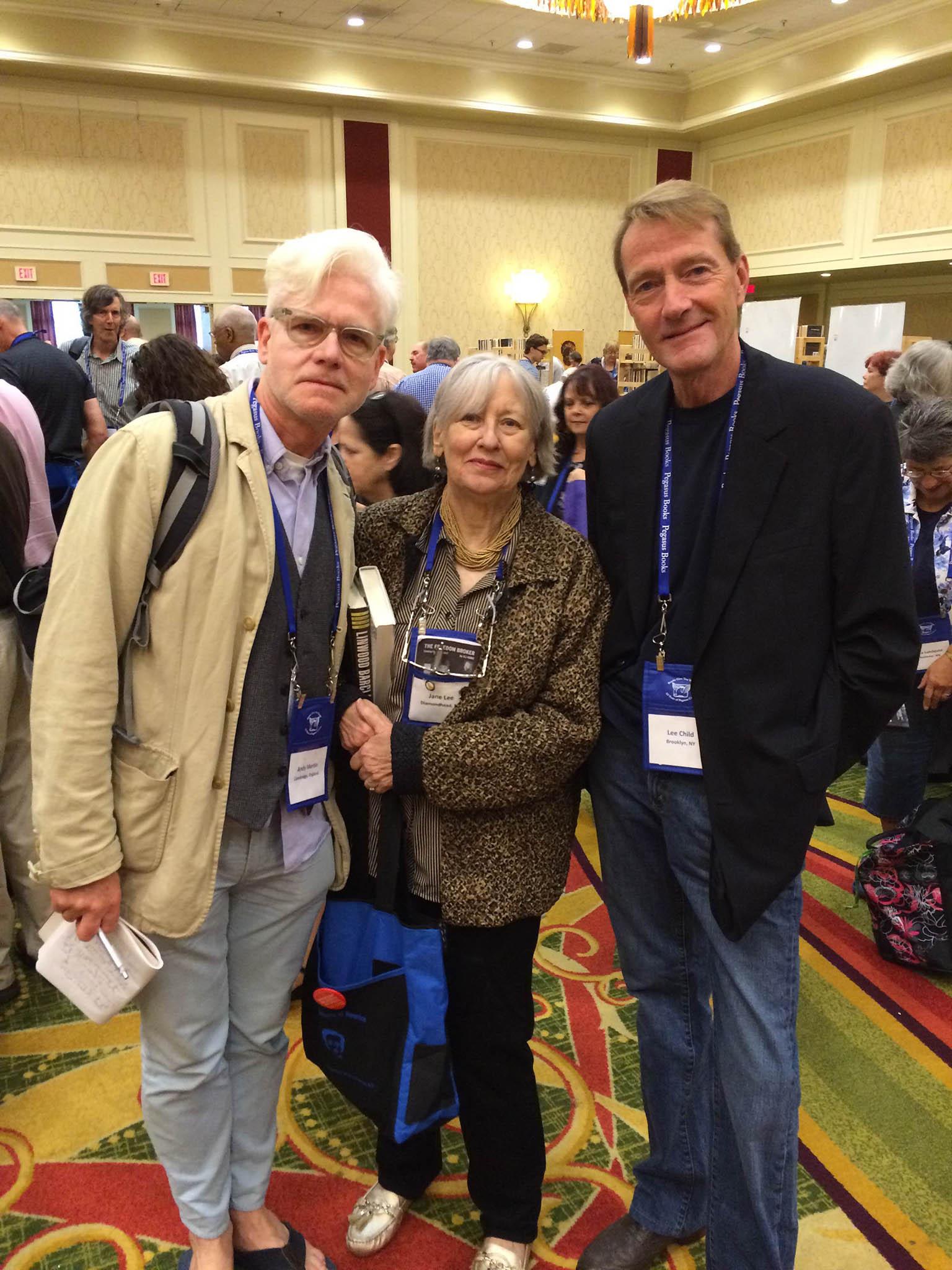

Andy Martin is in New Orleans for the biggest annual gathering of crime writers and fans in the world. While rubbing shoulders with the Slice Girls and Lee Childs, he asks crime-fiction buffs why they think the genre is soaring in popularity when actual crime is going down

They were always going to have a hard time getting the whip through Heathrow.

“It’s not a whip,” said the Slice Girls. “It’s a studded suedette flogger.”

“I’m going to have to check with my supervisor,” said the scanner guy. “Oi, Bill, is a whip a weapon or what?”

The rubber chicken escaped detection.

Direct from “Bloody Scotland”, they – the flogger, the chicken, several pairs of handcuffs, and a spanking feather – were all bound for Bouchercon, the biggest annual gathering of crime writers and fans in the world. This year it was in New Orleans. Which is where I first saw the Slice Girls, aka the writers AK (The Beauty of Murder) Benedict, Steph (Deep Down Dead) Broadribb, Louise (Venus Trap) and Voss et al strut their stuff. I should stress, they weren’t always wearing black corsets and fishnet stockings.

More than 1,900 people crammed into the precincts of the fiendishly air-conditioned Marriott Hotel in Canal Street from Thursday to Sunday. Global superstars such as Lee Child and Harlan Coben and Sara Blaedel (recently voted Denmark’s favourite author for the fourth time and translated into 33 languages), not to mention international rising star guest of honour (take a bow, Craig Robertson) were mingling with a legion of fans parading down the street on floats with a police escort and jazz bands and guys on stilts.

But there was a fundamental mystery that I was in New Orleans to try and puzzle out. Why is it that while actual crime is going down, crime writing is going through the roof?

Rambo was there. Not Sylvester Stallone, but David Morrell, the author of the original novel, First Blood. I met him in a bar on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter. He had a neat moustache, thinning hair, and no bandana. He was sipping a Sauvignon. Turns out he based it all on his own students. He was a young professor at Penn State at the tail-end of the sixties. And they were coming back from Vietnam, hardened vets, and wondering how come he had been marking papers all the time they were getting their arses shot off in the jungle. (He was Canadian.) So he asked himself, what if one of these pissed-off, alienated, grizzled, warrior hippies should turn a small town into a war zone?

Morrell got the name from his wife. Classic Genesis moment. He was struggling with the opening pages and he still didn’t have a name for his hero. He had actually written “blank”. Then his wife came home and offered him an apple. “Honey, I’m trying to write,” he says. “Come on,” she says, “it’s really good.” He succumbs and takes a bite. Which is when it all begins. “It is good,” he says. “What’s it called?” Answer: a variety of apple known as a “Rambo”. He liked the echo of “Rimbaud”, the French poet. If she had given him a Granny Smith history could have been different. And the brilliant opening sentence would never have been: “His name was Rambo, and he was just some nothing kid for all anybody knew, standing by the pump of a gas station at the outskirts of Madison, Kentucky.”

I bumped into Lee Child having a smoke outside and we had coffee together. Black. Like his hero, Jack Reacher, he only ever drinks black. Twenty or 30 cups a day. He said he’d just spent a week in the Orkneys and even there, in local news reports, he had come across the name Rambo twice, and nothing to do with apples either. “Rambo-like” behaviour. “It’s become one of the most powerful signifiers in the world,” he said. Maybe it is not so surprising that Child had to come up with a huge ex-military policeman vigilante, capable of quelling the most disgruntled, PTSD-fuelled, rampaging nutter with a single headbutt. His 21st outing, Night School, is published in November.

Symbolically speaking, Bouchercon was Apocalypse Now. Corpses everywhere. Sara Blaedel’s latest is The Killing Forest. I would estimate more than 50 per cent of the thousands of novels on offer had some variation on kill, killer, killing, die, death, or dead in the title. If you include subtle or not-so-subtle hints of violence in the offing, that percentage goes up to about 100. Rambo-like. I went to one panel (You Always Hurt The One You Love) which was all about who you want to kill. “If I want to kill someone,” Jeff Abbott (the Sam Capra series) said, “they’re already dead”. Probably everyone, I thought, given a fair shot, wouldn’t mind bumping off a few people. Maybe a lot. If they could just press a button. Crime fiction is that button.

I hope no one offs Jane Lee. I really liked her and her soft southern accent. She said she loved England and had been to “the best fish and chip shop” in London. We met in the “smart” elevator which had a habit of hitting the 30th floor when you only wanted to go to three. She had been to every single Bouchercon since 1988, including London and Nottingham, except for two. One, in 2005, because “my house in Mississippi had been blown away” (by Hurricane Katrina). The second time was in 2010 when her husband had a heart attack.

“You should have left him,” said Lee Child, signing a book, in his ruthless way.

“He is one of your biggest fans,” she said.

“Oh, well, in that case, I’m glad you stayed and looked after him. I hate to lose a reader,” he said.

Jane’s husband “gets so upset” at the sight of Tom Cruise playing the part of Jack Reacher in the movies (there is a new one premiering in October, Never Go Back). “Everybody knows,” Jane said, “Lee Child is Jack Reacher.” Fair comment, but so far as I know, Child was on his best behaviour and didn’t beat any bad guys to death with his elbows the entire weekend.

Down in the hotel bar, Mark Edwards was wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with a single word: ULTRAVIOLENCE. He is skinny and funny with square glasses and can sing Smiths songs from memory. He is also the author of a series of novels which have sold 1.7 million or so. He summarised his psychological thriller, The Magpies, as “neighbours from hell”. “The books are written so they can be described in three words,” he said. “And two of them are always ‘from hell’.” There is a schism in publishing between traditional print publishers and the new generation of online publishers. Edwards is published by Thomas and Mercer, the classy Amazon imprint, and has no less than four books currently in the Kindle top 20. You can actually buy his books too. They exist in the real world. But he can’t get the Waterstones in Wolverhampton to stock them, despite being huge. “It’s kind of embarrassing,” he said. “I don’t even ask them any more.”

I queued up to get my copy of Bone Dust White signed. American author Karin Salvalagio, based in London, wrote that I was fast becoming her “favourite stalker”. Nice. She had just finished participating in a collaborative experiment in which a short story was assembled by 20 or 30 writers, each one writing a sentence and then passing the laptop on to the next. She wrote: “Hector hesitated mid-grope.” Everyone in the hundred-strong audience burst out laughing when she hit the full-stop. They were probably expecting Hector to stop hesitating and stick the knife in.

On my last day in New Orleans, AK Benedict, not only the creator of a time-travelling serial killer but Slice Girl too, took me to a cemetery. The Lafayette Cemetery No 1. I should stress that she did not kill me and bury me in an unmarked grave. She only thought about doing that. She loves a good cemetery. Wherever she goes she likes to visit a cemetery or two. She has an English degree from Cambridge and has composed music for film and television.

Crime fiction is not really all about death, Alexandra argued, as we wandered about the tombs. It is not for necrophiles. Just like being in a graveyard, you, the reader, say to yourself, “at this time you are alive”. She added that the thought that “we all decompose in the end” made her feel “joyful”.

Mark Edwards, posing as a passing zombie, popped up from behind a crypt and said, “I need to write as many books as quickly as possible”.

“Is that a quest for immortality?” Alexandra asked.

“No,” he replied. “I just need to make a lot of money.”

Fictional murder is a celebration of life.

The French sociologist, Emile Durkheim, argued that the “function” of crime was to enable citizens at large to recognise themselves as law-abiding. I suspect part of the point of crime fiction is mimetic deterrence: to persuade criminals to behave for once. Bill Loehfelm, author of Doing the Devil’s Work, with a New Orleans-based detective, Maureen Coughlin, said that the silver lining of Hurricane Katrina was that it “eradicated crime completely for a while” because the gangs were blown not “out of the water” but into it.

The Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg rammed together Sherlock Holmes, Sigmund Freud, and an art historian under the heading of “the cynegetic paradigm”. He argued that they were all descendants of hunter-gatherers following a trail, like a dog (cynegetic from the Greek for dog, kunē) with its nose to a scent. Today’s Hercule Poirots and Sam Spades are still following the trail, deciphering the “hermeneutic code” (in Roland Barthes’ resonant phrase).

But seeing the Slice Girls on stage in the Voodoo Gardens at the House of Blues on Saturday night reminded me of exactly why so many of us are hooked on the genre. If I have read their stiletto semiotics correctly, their cabaret act simulates sex and death, as if to say these really are your only two options. Either/or, or possibly and, the unattainable alchemical formula of the coincidentia oppositorum. But of course there is a third way. The way of the Slice Girls themselves and the unlimited realm of crime fiction too. They exist in the twilight zone of sublimation between sex and death. Crime fiction enables us to kill the time between one and the other. It is neither/nor.

As I was finally leaving Bouchercon, I bumped into AK Benedict again, getting into a taxi. She was on her way to another New Orleans cemetery. Lafayette No 2 possibly.

Andy Martin is the author of Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of 'Make Me'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments