Boyd Tonkin: The man who starved literature?

The week in books

How much ought you expect to pay for a copy of Stieg Larsson's The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest? Buy the Kindle e-book edition from Amazon, in this case the guys who manage the hardware, the software and the retail pricing alike, and the answer this week is: exactly £2.68, or roughly as much as the posh frothy coffee you might drink while reading a few pages of it. Amazon's dead-tree paperback, for comparison, will set you back a comparatively steep £3.99. Not coincidentally, perhaps, the late Swedish spellbinder last month became the first author to sell a million electronic copies for the Kindle reader.

As the autumn publishing seasons nears with its routine harvest of inflated hopes and overblown claims, let's take a reality check. Just as the the newspaper business did a dozen years ago, when it chose to give its products away online without devising a credible method to replace abandoned revenues, trade publishing stands at risk of committing hi-tech suicide. True, digital distribution did not by itself inaugurate the crazed rush to strip perceived value from the art, skill and labour of writers everywhere, and to encourage younger consumers to treat literary talent – as they already treat journalistic and musical talent – as an effectively cost-free service that should arrive on tap, almost gratis.

In Britain, the catastrophic double whammy of the late 1990s – the abolition of statutory price maintenance for books, backed with a refusal to enact US-style controls on monopolistic discounts – soon seeded the belief that the proper value of an expensively-produced £20 hardback lay somewhere around £7.99. Supermarkets had already steamrollered publishers with their piled-high, flogged-cheap way with bestsellers when "kindle" still meant lighting a fire under a pile of unwanted paper. And, for all the company's control-freak paranoia about both technology and content, Apple has so far played relatively fair with publishers – and authors – to keep prices in its iBookstore at a level at which the art, and business, of the book has some hope of long-term viability.

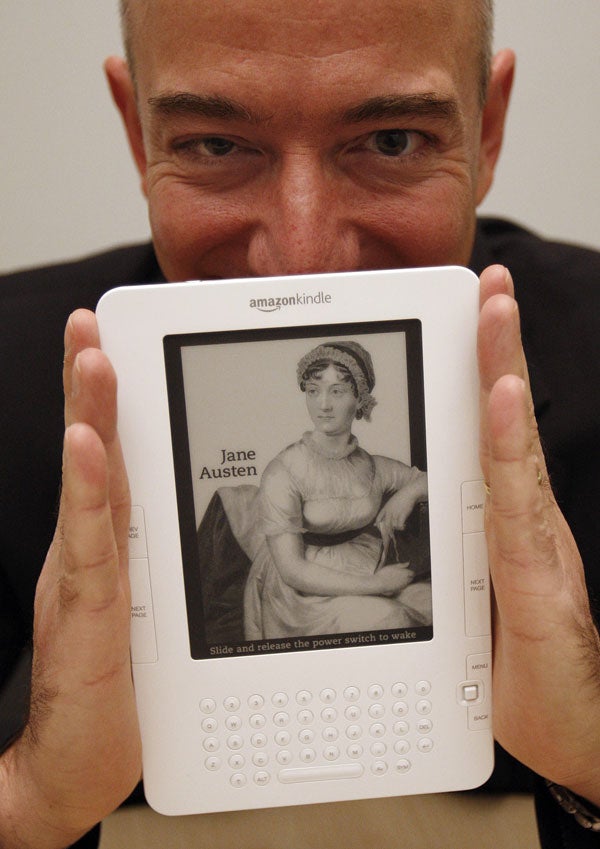

Amazon, with its more varied, inexpensive lines of kit and broader range of titles, looks well placed to resist Apple's bid via the iPad to become the retailer of choice for digital readers. Yet Jeff Bezos's company has also led the race towards all-but "free" content: a plunge to the depths that, as e-reading develops, threatens to drown writers and publishers alike. All the same, the cultural shift marked by the crash of virtual reading onto the bargain-basement floor runs deeper than any hunt for corporate villains (or heroes).

Can professional authorship even survive, in the post-Enlightenment sense of a body of individuals who may reasonably hope over a career (rather than via one-off sensations) to gain a livelihood chiefly from the composition and sale of book-length works? Certainly it will, for the blockbusters and brand-creators, and the odd literary superstar. But the corps of full-time pros will shrink – perhaps drastically so.

Remember, though, that this status has always been much rarer than book-trade hype implies. Cross-subsidy from other jobs, other writing and family support has traditionally sustained serious literature, both fiction and non-fiction. It will do so in spades over the coming years of digitally squeezed margins and slashed incomes. Already, the bulk of well-known writers earn – from their published work alone – less than readers think they do, especially the "literary" novelists. One still sees fantasy numbers quoted for book advances that overshoot any likely figure by 1000 per cent and more. They will soon earn even less.

For the ambitious novelist, the portfolio career awaits. They will live as poets always have, with fees from teaching, performance, festivals, editing, broadcasting and journalism now combined – as media and education also suffer cuts – with quite separate trades. If I were a university creative-writing head, I would now be starting to plan joint degrees in Landscape Gardening and Literary Fiction; in Psychotherapy and Biography; or (given the shining examples of TS Eliot, Roy Fuller and Wallace Stevens) in Financial Services and Modern Poetry.

Good, even great, writing, will flourish, as it did and does in all those poorer countries where gifted authors have never had the chance to write for cash. Who knows? The evaporation of rewards from the commercial marketplace may strike many authors as a liberation from pressures to conform. But writers themselves, along with their readers, need to think and talk in earnest about the future economics of their calling. So far, this conversation has scarcely begun.

The president's freedom to read

Being President means that you get to read hot books before the hoi polloi. At the Bunch of Grapes bookstore in Martha's Vineyard (right), a vacationing Barack Obama bought titles by John Steinbeck and Harper Lee (but surely the legal eagle read To Kill a Mockingbird while in short pants?). He was also gifted an early copy of Jonathan Franzen's Freedom. A mighty fanfare has anticipated the novel's release - but it's not on sale yet. Cue US outrage over the discovery that retailers and media receive advance proofs. Disgusted of Brooklyn is welcome to bid for The Independent's own preview copy. Will exchange for dinner (and round-trip fare) at L'Etoile, Edgartown, Mass.

Farewell to a modern master

Among my (and no doubt your) least favourite genres is the fond reminiscence by middle-aged buffers of the giants who stalked lecture-rooms in their student days. Undeterred, I have to mark the passing (aged 90) of Sir Frank Kermode, Manx lorry driver's son, quizzical wartime naval officer - see his lovely memoir, Not Entitled - and a paragon of mind-expanding criticism. With Kermode, ever-adventurous ideas and searching scholarship went hand-in-hand with modesty and accessibility. Once upon a time at Cambridge, students might learn from a trio of giants – each, in his own way, semi-detached from the powers-that-be – how to trace the paths that led from the EngLit canon into a thrilling hinterland of thought that stretched in space all over Europe, and beyond, and in time from the Classics to the present: Frank Kermode, George Steiner and Raymond Williams. Each could (and did) in a different style demolish the myth of the Golden Age. But who, in any university, has since filled their shoes?

b.tonkin@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments