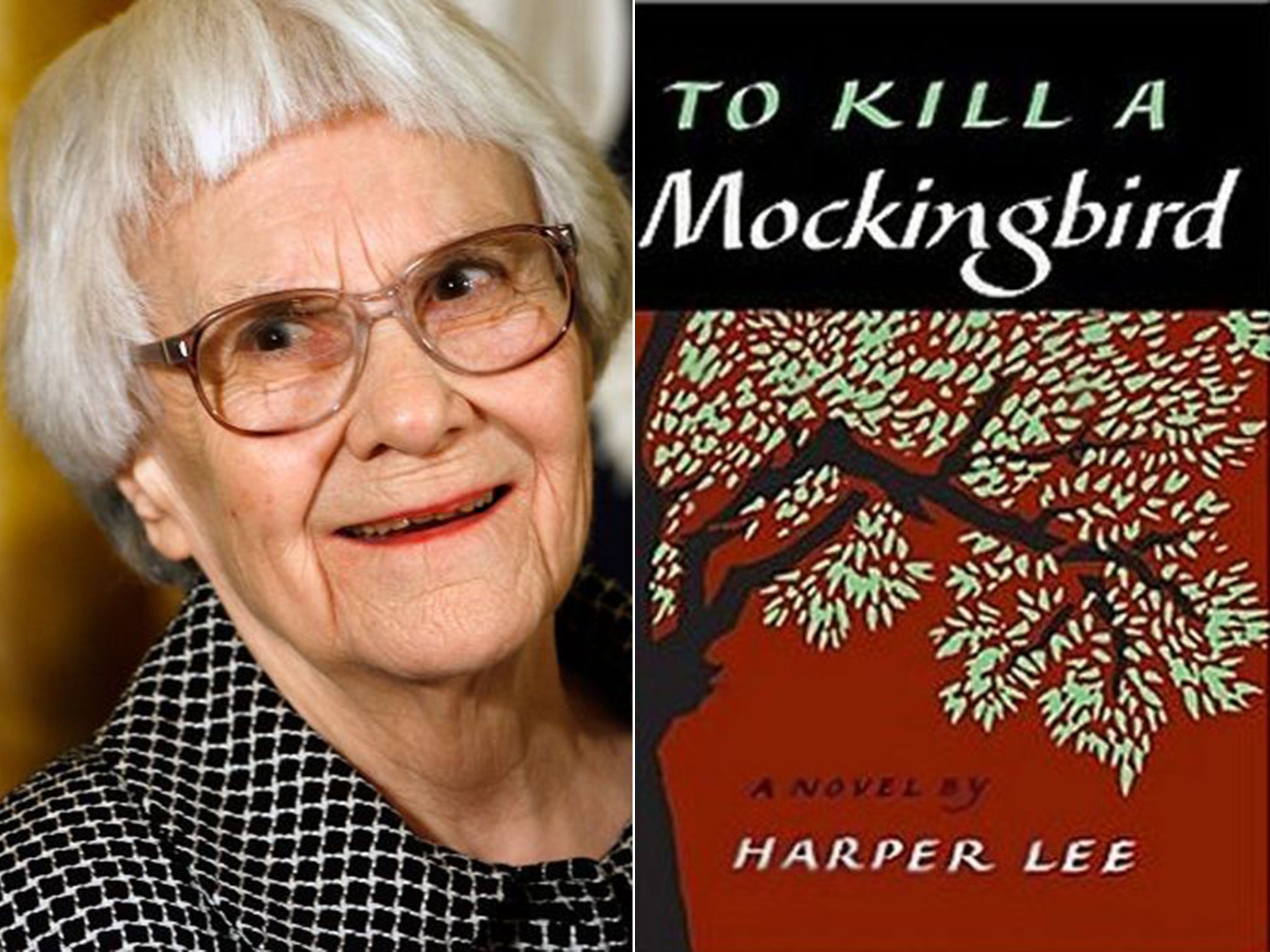

Go Set a Watchman: Is the prospect of another book from Harper Lee a potshot at the Mockingbird, or a literary coup?

The sensational news of the publication of a second novel by the Pulitzer Prize winning author has sparked debate across the world

She is the mockingbird. That much is clear this weekend as the world goes crazy about the prospect of another book from Harper Lee, more than half a century after the first.

The woman who wrote To Kill a Mockingbird is 88 years old and uses a wheelchair, after a stroke. She is profoundly deaf, almost blind, and lives in a care home on the outskirts of the small town in Alabama where she was born. She has become the recluse people always thought she was, when actually she was just avoiding the extreme fame that goes with writing one of the best-loved novels of all time.

To Kill A Mockingbird won the Pulitzer Prize and has sold 40 million copies, but the author fled from the limelight. Lee has not given a proper interview since 1964.

Now only the closest friends get into the Meadows of Monroeville assisted-living facility on Highway Bypass 21. Even Oprah Winfrey was turned down for a television interview a few years ago, being told over a private lunch: “I am really Boo.”

That was a reference to her character Boo Radley, the reclusive neighbour who strikes fear into the heart of the young tomboy heroine, Scout, but ends up saving her life.

Boo is compared in the book to a mockingbird: a harmless creature that should never be hunted but left alone to sing as it chooses – and it is clear from what Lee said to Oprah that she sees herself in that way too. Yet here she is this weekend, the publishing sensation of the century.

Go Set a Watchman is already top of the charts on pre-sales. This story about the adult Scout will be published by HarperCollins in the US and Penguin in the UK on 14 July.

A statement released in the name of Harper Lee said: “I’m alive and kicking and happy as hell with the reactions to Watchman.”

But it was just a statement, and some people are worried. They remember that at the end of Mockingbird, the local sheriff refuses to tell anybody that Boo Radley has been a hero. He fears Boo will not cope with the attention. Forcing him to do so is compared to shooting a defenceless bird. And they wonder if that is what’s happening to Lee. Or, as Mia Farrow put it on Twitter, “Is someone taking advantage of our national treasure?”

Scout quotes her father in saying: “You never really know a man until you stand in his shoes and walk around in them.” We can only guess what it is like to be in Harper Lee’s shoes right now.

The Rev Dr Thomas Lane Butts, a friend over many decades, used her real name when he expressed concern. “Nelle’s had a stroke, a lot of things she doesn’t remember. She’s confined to a wheelchair, essentially blind and profoundly deaf. You draw your own conclusions.”

The manuscript is said to have been found by accident, as her lawyer Tonja Carter flipped through a draft of Mockingbird. It was clipped to the back.

The startling and lucrative find was made in September, but did not become public until after the death in November of Lee’s big sister, confidante and lifelong legal adviser, Alice, at the age of 103. Charles Shields, who wrote an unauthorised biography of Lee, said: “I doubt whether Alice would have allowed this project to go forward.”

Family friends who were at Alice’s funeral told Associated Press that Nelle “talked loudly to herself at awkward times during the service”, and “mumbled in a manner that shocked some in attendance”.

No doubt she was deep in grief, which is not evidence that her mind is going. Nor is her physical disability, of course. Her literary agent, Andrew Nurnberg, said she was “feisty” and “funny” during a visit to her in January. “This isn’t somebody with dementia who is being led up the garden path.”

The historian Wayne Flynt said his close friend was “quite lucid” last Monday. “I don’t think anyone would have done this without Nelle’s full knowledge and consent,” he said.

It’s impossible to tell, as reporters are turned away at the Meadows. The residents of the 16 bedrooms there have meals, laundry and housekeeping taken care of. Staff are on hand around the clock. Fees start at $69 a day.

It is ironic that Lee should be the focus of so much attention in a home so close to the small town she fled in the 1950s, to escape the feeling of being watched all the time. To Kill a Mockingbird is set in a claustrophobic town in the Deep South, a thinly disguised Monroeville.

Her darn good yarn has enabled generations of Americans to empathise with those caught up in racism and injustice. Published during the struggle for civil rights and studied in most schools, it has become one of the foundational stories of the nation.

Mockingbird is hugely popular in this country too – British librarians voted it the number one book every adult should read before they die.

But let’s be honest, not everybody who has talked about the book in the last week has actually read it. Soaring sales suggest quite a lot of us are trying to catch up. Study notes are available, but it concerns a young brother and sister, Jem and Scout Finch, who watch their lawyer father, Atticus, try to save a black man accused of rape.

Atticus is loosely based on the author’s father, Amasa Coleman Lee, who once defended a black father and son accused of murder. But they were hanged, and he gave up criminal law to specialise in tax; he also part-owned the local newspaper.

Jem and Scout have a companion in the book: Dill, a precocious child modelled on her real-life neighbour Truman Persons.

The boy who was Nelle’s constant companion became the acclaimed writer Truman Capote. They went to the courthouse for fun, he remembered. “We went to the trials instead of going to the movies.”

Both stood out. At college in Montgomery during the war, Lee rejected rigid female fashion codes and became known for wearing her brother’s old bomber jacket from the Army Air Corps, smoking a pipe and using “salty” language.

Capote was already in New York when she dropped out of a law degree in 1949 to join him.

She worked as a booking agent for the airline BOAC and wrote in her spare time, but at Christmas 1956 she was given a year’s salary by Michael Brown, a Broadway lyricist. The note read: “You have one year off from your job to write whatever you please. Merry Christmas.”

Still, the result was mostly short stories. It took two and a half years more for the editor, Tay Hohoff to help her create a novel. Actually, as it now turns out, she had created two. Lee first wrote Go Set A Watchman about the adult Scout, with flashbacks to her time as a child in Alabama. The editor told her to take out the flashbacks and use them for another novel.

“I was a first-time writer, so I did as I was told,” she said in a statement last week about the new – or rather very old – book. The flashbacks became Mockingbird, while the rest of the story was put aside and forgotten.

“I hadn’t realised it had survived, so was surprised and delighted when my dear friend and lawyer Tonja Carter discovered it. After much thought and hesitation I shared it with a handful of people I trust and was pleased to hear that they considered it worthy of publication.”

Rumour has always had it that Capote actually wrote To Kill a Mockingbird, but Lee said: “That’s the biggest lie ever told.”

The rumours may be fuelled further if Go Set a Watchman is terrible – but there are already claims he wrote that too.

AC Lee was amazed by what his daughter achieved, saying: “It’s very rare indeed when a thing like this happens to a country girl going to New York. She will have to do a good job next time.”

He lived long enough to see her win the Pulitzer in 1961, but died before seeing Gregory Peck win an Oscar for playing a version of him in the movie.

When asked how she felt about writing a second novel, Lee said: “I’m scared.” Instead of publishing any more, she dropped almost out of sight. She would turn up for an award or degree, but never make a speech.

The anonymity of New York suited her, and when she stayed with Alice in Monroeville, they were seen around town doing ordinary things, eating out at Burger King or McDonald’s. Those due to meet her were warned not to talk about Mockingbird. Her love-life was also off limits.

Then came the stroke in 2007 that put her into hospital, followed by assisted living. Oprah was granted a private lunch a couple of years later, and asked Lee why she had never published anything more.

“I already said everything I needed to say,” was the answer. Everyone who thought she was Scout was wrong. “You know the character Boo Radley? Well, if you know Boo, then you understand why I wouldn’t be doing an interview, because I am really Boo.”

Boo Radley’s heroism is kept a secret in her book. Scout says she understands why, and knows what the attention would do to him. Her words come to mind this weekend.

If Harper Lee’s lawyer and publishers have her full permission and she understood what was being asked of her, as they insist is the case, then Go Set a Watchman is nothing but a glorious thing.

But if by trying to put ourselves in her shoes we imagine an old, deaf and blind lady being taken advantage of at a time of grief, then we have to worry, look for reassurances and quote Scout again: “Well, it’d be sort of like shootin’ a mockingbird, wouldn’t it?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments