How did our legends really begin?

A new theory suggests that the similarities shared by many myths means that they have a common origin, passed down across thousands of generations. So, how did our stories really begin? Steve Connor reports

In the great mythological narrative of Homer's Odyssey, the hero lands on the island of Sicily, the home of a race of one-eyed monsters, the Cyclopes. Finding a cave filled with a flock of sheep, the hero and his men feast on one of the animals until they are rudely interrupted by the cave's furious owner. The Cyclops Polyphemus vents his anger by eating a couple of the intruders before blocking the cave's entrance with a giant boulder.

When Polyphemus returns to eat more of Odysseus's men, the Greek hero manages to spear the eye of the Cyclops. Blinded, Polyphemus attempts to keep the men captive in the cave by feeling the backs of his sheep as they emerge each morning to graze. But Odysseus and his men hide beneath the bellies of the animals and so escape the monster's grasp.

Although Homer wrote the Odyssey in the 8th century BC, this particular part of his epic poem has a surprising resonance with other folklore and oral traditions spoken in the Swiss Valais of Central Europe, in the Basque country of northern Spain, in Russia, among the Saami of northern Scandinavia and the Apaches and other Native American tribes. They all speak of a fearsome master of animals, a hero who loses his way and is held captive but who escapes by hiding under the master's own animals.

The similarity of the narratives could be just coincidence. Each culture might just have devised its own folklore independently of the other, coming to surprisingly similar storylines. But many myths seem to share similar incidents, characters or narrative structures, whether they derive from classical Greece or the ancient mythologies of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Japan or India.

When you start looking at these similarities you begin to wonder whether they could have had a common origin, perhaps carried from one part of the world to another as Palaeolithic peoples migrated over many thousands of years to colonise new lands. Could the legends and folklores of the world be connected in the sense that they stem from a common origin, passed down by word of mouth over several thousand generations?

This, fundamentally, is the radical idea of Michael Witzel, a Harvard University linguist and philologist, who has drawn on the scientific disciplines of molecular genetics, physical anthropology, archaeology, and his own field of linguistics to propose that the world's many mythologies have a common origin – similar to the evolution of related species from a long-extinct common ancestor.

Witzel argues in his new book, The Origins of the World's Mythologies (OUP), that the myths and legends of today's world cultures can provide important insights into the earliest myths as they were told by the first anatomically modern humans more than 100,000 years ago, the time of "African Eve", the last common ancestor of all our mitochondrial DNA.

This would mean that some myths have survived being told over somewhere in the region of 3,000 generations. Surely, this is impossible given our experience of how stories are misconstrued by Chinese whispers when related from one person to the next?

"The setting of telling myths is different from that of Chinese whispers," Witzel says. "Such myths are told in a formal, ritual, sometimes secret setting. Their telling is also different from that of stories for the amusement of children. Frequently myths are transmitted in a formal way from teacher to student, for example from shaman to apprentice."

Witzel, a Professor of Sanskrit, is familiar with the linguistic idea of a pre-historic "proto-language" spoken in the Palaeolithic from which all other languages have evolved. The same goes for a kind of proto-mythology that began deep in the Stone Age when Homo sapiens fashioned crude flint tools, was fond of living in caves decorated with animal drawings and could evidently think in symbolic terms, especially fruitful around a camp fire at night – the best time for telling stories and asking big questions about the meaning of life.

Just as Darwinian biologists can detect the main evolutionary branches in the "family tree" of life, Witzel believes he can detect a big split in the evolutionary tree of mythology which gave rise to two broadly different lines of myths he sees today. By analysing the structure and content of thousands of myths, Witzel says it is possible to see a division into two lineages, which he has called Laurasian and Gondwanan, after the geological names for the two ancient supercontinents of the northern and the southern hemispheres that existed 200 million years ago, long before the arrival of the first humans.

Gondwanan mythology is more ancient of the two, and survives today in the "southern" cultures of sub-Saharan Africa, stretching in a narrow arc to Australia, taking in the cultures of the Andaman Islands, New Guinea and Melanesia. The northern Laurasian mythology, meanwhile, covers Europe, Asia and the Americas and differs substantially from the older Gondwanan mythology, Witzel says.

"Laurasian myths share a common storyline that tells of the creation, in mythic time, of the world, of several generations of deities during four or five ages, of the creation and fall of humans, and finally of an end of the universe, sometimes coupled with the hope for a new world," he says. "Laurasian mythology was successful as it put essential questions and answered them in a satisfactory way. It asked the eternal questions 'where do we come from?', 'why are we here?', 'where do we go?' and answered them by stating that we are descendants of the gods, who on their part have evolved from early generations and ultimately from the universe itself, whose ultimate origin is prominently debated."

Gondwanan myths, meanwhile, are notable for their lack of a narrative about creation and the origin of the universe. In these more ancient, "southern" myths, the Earth and Universe are supposed to pre-exist and their main focus is on the creation of humans and their culture, Witzel explains. Often the creator in Gondwanan mythology is a deus otiosus, or "idle god", who withdraws back into the sky after the act of creation.

"The Gondwanan mythologies do not have the continuous storyline nor accounts of the beginning and end of the world; rather, they are interested in the origins of humans… There are variations: men may be fashioned from clay or wood and we also encounter animals who may transform themselves into men… but in all cases, the universe is already there," he says.

The geographic separation of Laurasian and Gondwanan mythologies fits neatly with the proposed migratory routes of the earliest Homo sapiens as the species emerged "out of Africa" around 60,000 years ago. Genetic and anthropological evidence suggests that the first African migrants crossed into Arabia from the Horn of Africa, then slowly migrated south-east following the seafood-rich coastlines of the Arabian Peninsula, India, Southeast Asia and Indonesia, where they made their way by boat to Australia.

The anthropologist Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London and pioneer of the "out of Africa" theory of human evolution and global colonisation, says Witzel's hypothesis has an air of plausibility about it. "This is big and brave thinking… Witzel has seemingly done a great deal of research to back up his big idea."

The out-of-Africa theory of human history says that at some early point when the first humans were in Asia, a branch of humanity headed north when the climate warmed, possibly about 40,000 years ago to the Middle East, Europe, China and eventually the Americas, crossing a land bridge at the Bering Strait connecting Asia to North America about 20,000 years ago. It is this northern migratory band of humans, according to Witzel, who gave rise to the Laurasian branch of mythology, with its distinctive narrative storyline, big ideas on creation and the mythic belief that humans can be the living descendants of the gods.

"The Laurasian mythology began about 40,000 years ago and is characterised by a story-line extending from the beginning of the world – and of humans – to its final end," he says.

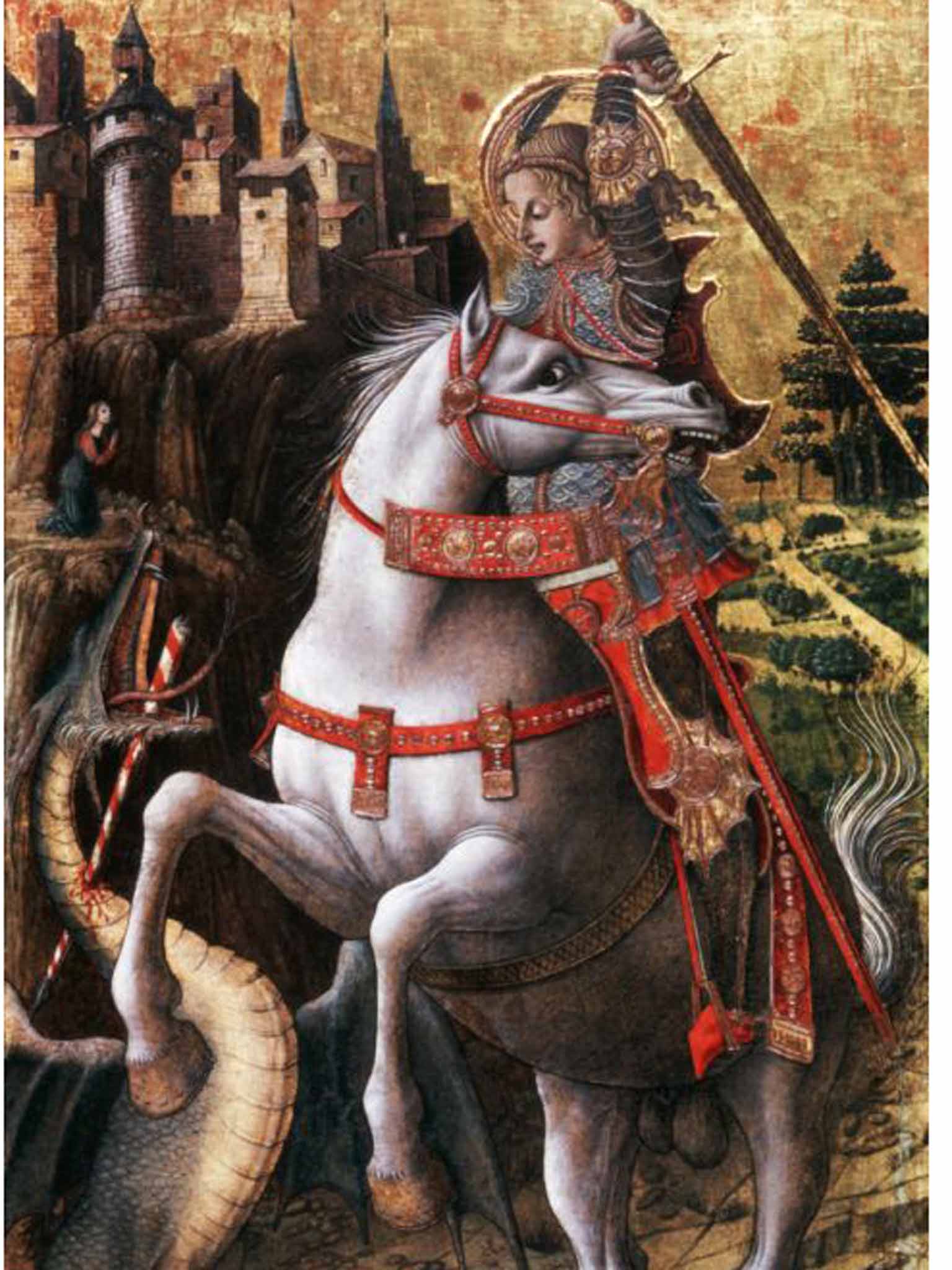

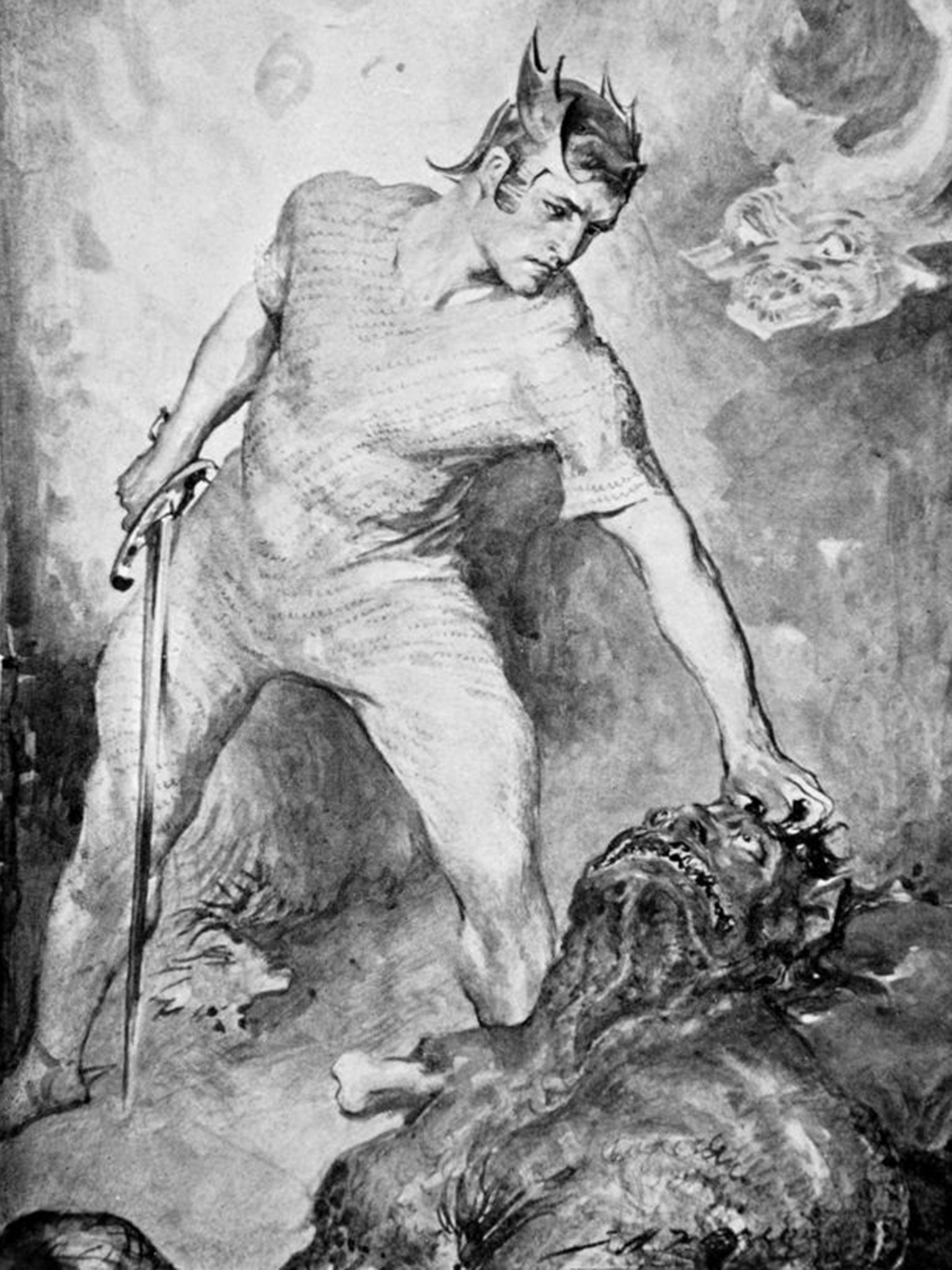

In typical Laurasian mythology, the act of initial creation is followed by the first gender-based beings, usually Father Heaven and Mother Earth, who give rise to subsequent deities. Once heaven and Earth are separated from a primordial "darkness" or "chaos", Earth can be prepared for the arrival of the first humans, often by the slaying of a dragon or serpent – a recurring theme in northern Laurasian mythology, whether it is the Nordic stories of Beowulf, the Navajo folklore of the American south-west, the Egyptian god Seth who fights the reptilian Apophis, the Mesopotamian Marduk triumphing over Apsu, the Indian Lord of Thunder Indra killing the serpent Ahi, or the Japanese Shinto god of the sea, Susanowo, who rids men of the eight-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi – not forgetting the Chinese goddess Nuwa and the black dragon, and of course our own dragon slayer, St. George.

In many of the ancient Laurasian myths, humans are the descendants of the Sun deity while in later Laurasian myths that emerged in the Neolithic, noble families reserved this lineage for themselves – hence the God-like rulers of ancient Egypt and Polynesia, Witzel says.

One thing that unites the older Gondwanan mythology with Laurasian, is the idea of a catastrophic flood that wipes out much of the world, leaving but a few to survive. Followers of the Abrahamic religions – Jews, Christians and Muslims – will immediately identify the story of Noah in the Old Testament. But the story of a great flood goes far deeper into pre-history, such as the great deluge in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and extends geographically to the Gondwanan myths of sub-Saharan Africa and aboriginal Australia, Witzel says. The recurring theme is a flood as retribution for human misdeeds, involving a few chosen survivors.

Witzel originally thought the flood myth was solely a feature of Laurasian mythology but he also sees it in Gondwanan myths. Indeed, he believes it is so ancient as a theme that it belongs to even earlier mythological roots than both Laurasian and Gondwanan, which he calls "Pan-Gaean", after the ancient supercontinent that existed before Laurasia and Gondwana.

Witzel's book has received little publicity, but one academic review, by another Professor of Sanskrit, Frederick Smith of the University of Iowa, suggests this could change: "His reading is epic… and this book will receive epic discussion." Witzel, meanwhile, hopes that his theory will act as unifying balm in a troubled and ideologically divided world: "Hopefully, it helps in underlining basic human unity, as we all have the same spiritual origins."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks