Leonardo Padura's revolution in crime

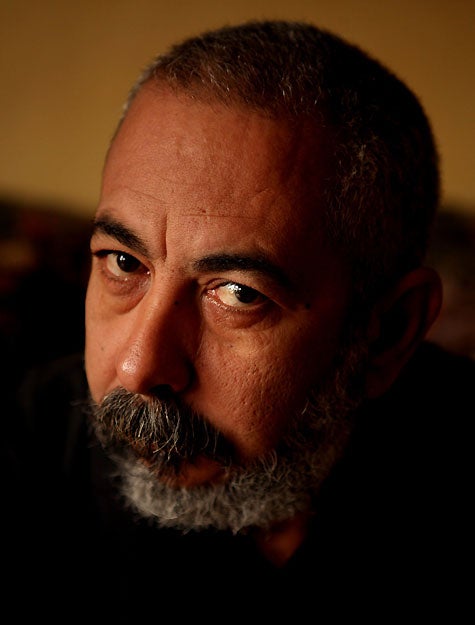

With his Havana Quartet of mysteries, Padura turned Cuba's history into gripping and atmospheric fiction. Jane Jakeman meets the boy from the barrio

Leonardo Padura's prize-winning series of novels about Cuban detective Inspector Mario Conde has changed the face of Latin American crime writing, taking a conventional formula into the category of dark and serious literary fiction. Havana Gold completes his sweeping portrait of Cuban society, seen through the ironic vision of his louche, sensual and intelligent cop. Here, Conde searches for the murderer of a teacher who has been strangled, and the quest takes him back to the school where he studied.

Padura has written of Conde as whispering in the writer's ear, and of the Havana Quartet as a joint decision between character and author. Yet Conde, though he has many consolations in the form of cognac, cigars and occasional sexy women, sometimes suffers from a form of anomie that leaves him in despair. During his visit to London, I ask Padura, a man of warm and lively empathy, whether he and Conde are one and the same. He explains that Conde is a pair of spectacles through which he can observe Havana.

"Conde is fiction, but he has many of my own characteristics," he says. " We belong to the same generation. This is a very important thing in Cuba, because it's the generation that was practically born with the revolution. All my intelligent life happened with the revolution. We grew up in its romantic period – the Sixties and Seventies. I remember in school we had posters that said that the future of humanity belonged completely to the socialists.

"But in the Nineties," he continues, "everything changed." Like Conde, Padura seems a disillusioned left-wing romantic. "That future disappeared," he says, "and Mario Conde is in many ways the result of this disappointment. But he has his own life. He's not an alter ego."

Nor does Padura share Conde's bad luck with women – the detective is susceptible but the perfect woman always seems to elude him. Padura and his wife, Lucia, have been together for 30 years. She is the first reader of all his work, and a very significant partner. He comments that they are like two gear-wheels with different speeds. If he goes too fast, she slows him down; if he is too slow, she speeds him up. "All my work is part of this relationship with her."

Conde is not really a macho character: he's sensitive, a great reader, not interested in power over others. I wonder why "the Count" had become a policeman in the first place. "'Conde is not the guy to be a policeman," his creator agrees. "He is soft. But in the beginning, when I was writing Havana Blue, you couldn't have a character who carried out detective-style investigation in Cuba unless he was a policeman. In each novel, Conde distances himself further from the esprit de corps and discipline of the police. In the next novel, he will become a dealer in second-hand books, similar intellectually to the work of a policeman, but with more sensitivity." In the Nineties, there was a major crisis in Cuba because of the withdrawal of Russian aid, and book-dealing "became a very important business, because many people sold their libraries".

His love of literature is a prominent characteristic of Padura's detective. There's a passage in Havana Gold (translated by Peter Bush; Bitter Lemon, £8.99) which tells us that Conde never lends his books. Padura laughs when I quote this. "I say you should never lend your books to your enemies, you lend them to your friends." He bangs the table emphatically. "And the sons of bitches never return them!"

Havana Gold tells us of Conde as a boy in the barrio, dreaming of being a writer. Did this reflect Padura's experience? "Not really, because I discovered I wanted to be a writer at university. When I was young, I was a normal boy, my big ambition was to be a baseball player. I played baseball every day, every hour of my life. Maybe the spirit of competition it awakes in the young is important. At the university, where I graduated in Hispanic philology, I had certain classmates who wrote poems and short stories, even a novel, and I decided I could write too. Because of this spirit of competition, I began to write. But the authors Conde loves are the authors I love."

Pre-eminent among them is Hemingway, but Padura is clear-eyed about his hero. "Hemingway is a special part of my relationship with literature... I began to have the image of the writer as a man like Hemingway, who has participated in many things, in war, a man of action, yet living in a romantic period, in Paris... He was the model of the life of a writer. I began to read Hemingway and discovered that his style was for me, and I thought that to write like him could be very easy. I began to write my short stories like Hemingway."

However, he discovered "that all that life of Hemingway was a contradiction, in which he was very hard with many friends such as Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, hard on women – and I discovered at the same time that to write like Hemingway was very difficult! But Hemingway was one of the authors who gave me a consciousness of both the life and work of the writer."

Padura quotes in the preface to Havana Black the Mexican writer, Juan Rulfo, who recommends that the author should "write with an axe". He explains how significant this is to him: "Rulfo wrote only two books, a volume of short stories and a novel of 180 pages [Pedro Páramo]. He is a classic of Spanish literature. You could say he was like Hemingway but with another kind of imagination, a mix of the Mexican Indian and the Spanish. But he is like Hemingway in the sense that he puts in a book only what is necessary. You take an axe to cut out everything that you need to cut out of the book and only the essence is important." Amiably, he adds, "With the novel I am writing now, I use an axe every day."

The books are filled with powerful descriptions of Havana. "I have a study with a small library with a big window looking on to the garden, where I smell the flowers and see the colours, hear people talking in the street – when I have to close the window in winter, it's not the same. I walk through Havana with my eyes open. I try to see and hear the people. The most important thing is the language of the people, because through their language you discover how they think... Havana is a character. It's the third man in my novels – there's Conde, the plot of the book, and the atmosphere of Havana."

Conde describes himself as "anchored in Havana". Does Padura, who could now live anywhere he chooses, feel also anchored in his city? "I have a complete sensation of belonging to Havana, but more than that, to my neighbourhood. I live in the barrio where my father, my grandfather, my great-grandfather, lived. It's not beautiful, but it's the place in the world where I can be really the person that I am. For years many people in the area didn't know that I wrote novels, or that I was a journalist – I was just the son of my father and mother, a normal child of the place."

Padura needs "to hear the people in order to find my stories, my language and atmosphere, to find the sense of reality. When my wife and I were walking in London, we said London is beautiful, so is Paris, or a Greek island – but Havana is completely different.... Carlos Acosta [the Cuban dancer] can live in London without problems because he has a different kind of art. But to write, you need the sensation that you are in a world that you first belong to and later that you dominate. Conde and I are part of this sensation."

He talks animatedly of the Latin American tradition. "My literary generation, who wrote mainly in the Eighties and Nineties, rejected the influence of the previous masters, Borges, García Márquez, because with many of these writers you can only be an imitator." Magical realism was not a significant model for this young, politicised generation. "We tried to write about reality, with verisimilitude, in everyday language: urban literature, always set in the cities, in the streets."

Padura warms to this theme: "As a Cuban writer, I have a certain responsibility because our reality is so specific and so hard for many people. I have a responsibility to reflect something of my world." This sense of responsibility extends to remaining among the people of the barrio. One gets the sense that he would never leave Havana, and devotion to Cuba would override any scepticism about the new regime. Like Conde, he is an inextricable part of his environment.

Biography: Leonardo Padura

Leonardo Padura was born in Havana in 1955. He studied in Havana and remained in Cuba throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, when the country underwent an economic crisis as Russian aid disappeared. Padura became a journalist, writing a popular column and editing the leading cultural magazine, La Gazeta de Cuba. He wrote short stories and essays, but first found international recognition with the Havana Quartet of crime novels featuring Inspector Mario Conde (Bitter Lemon), the latest of which is Havana Gold. Padura has won numerous awards, including the Spanish award for detective fiction, the Premio Hammett. He still lives in Havana, in the barrio where he grew up, with his wife, the journalist Lucia Lopez Coll.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks