London International Antiquarian Book Fair: original letters from Orwell and Carroll reveal lots about the famed authors

A Plaintive letter from Lewis Carroll that is a masterclass in self-exculpation

Dangerous stuff, writing. “Give me six lines written by the most honest man in the world,” wrote Cardinal Richelieu, “and I will find something in them to hang him.” Indeed. And show us the private correspondence of the most elevated literary figures and some revelation about their character will soon become apparent.

The evidence is available at the 58th London International Antiquarian Book Fair, which has been running at Olympia since Thursday. Alongside the first editions of Ian Fleming and TS Eliot, there’s a distinct buzz about original letters written by literary titans, that reveal their authors in unexpected ways – and their quality is reflected in the prices.

On stall A02, Sophie Dupre, for 40 years a dealer in “autographs, manuscripts, signed photographs, books and literary property”, is selling a trove of letters from Victorian writers, displaying their preoccupations in print. Here, for instance, is DH Lawrence, abandoning his habitual seething fury to write, semi-flirtatiously, to his sister-in-law Else in 1927 – chatty domestic detail, about her gifts, comments on the weather, even a few words in German – before getting round to asking her to translate The Plumed Serpent for the German edition. Yours for £1,775.

Here’s Anthony Trollope, author of the Barsetshire Chronicles, replying in 1875 to a request from a Dr MacLeod for a Yuletide tale for his publication. Trollope’s reply will be familiar to any over-stretched hack: “I find that 25 of your pages will considerably exceed 100 ordinary novel pages. I could not do this amount of work for £75 guineas. I will do it, if you like, for 100 guineas… But I shall not be sorry to see the task go elsewhere, as it is always hard for me to cudgel my brains for a Christmas story.”

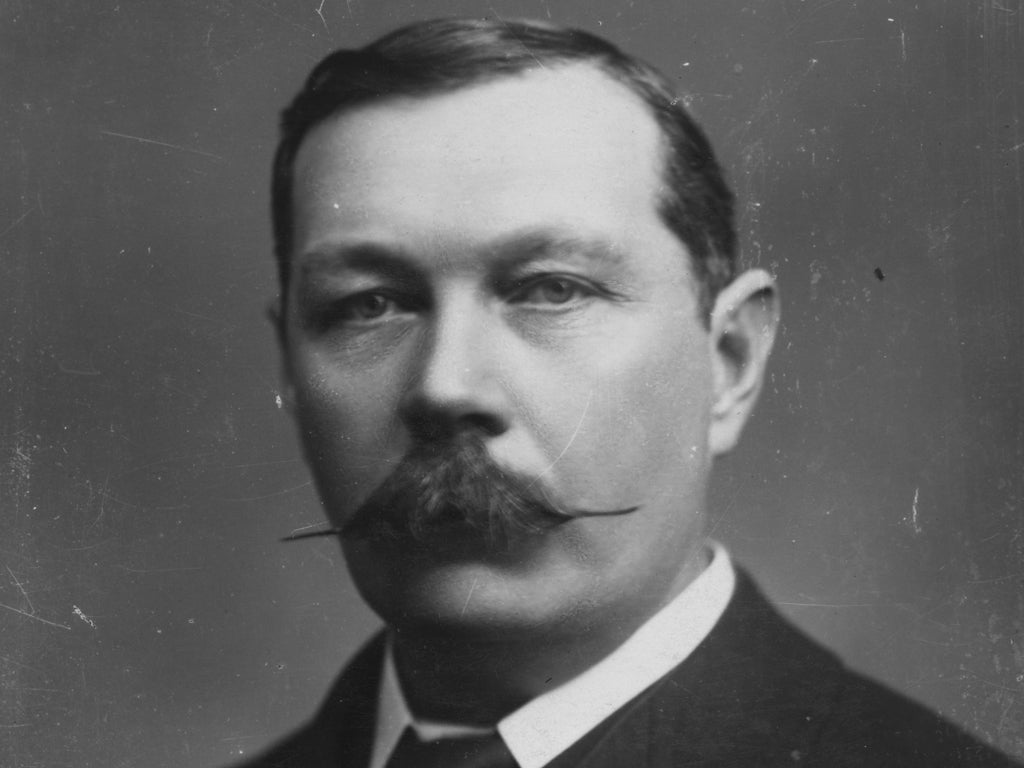

Look at this 1926 letter from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to an Austrian general, who has invited him to give a talk in Vienna. The handwriting in Doyle’s reply is firm and, for a medical man, surprisingly legible: a commonsensical missive, you think, uttering a gruff refusal. But on the second page, it goes off into advanced loopiness: “More and more I see that the phenomena are nothing – mere signals in order to call our attention – to the messages, the first clear detailed account of what awaits us beyond the grave which has ever been made to the human race. When the certainty of this is realised, it will give a common bond to all mankind, draw the various religions and nations closer together, and make the improvement of character and unselfishness the obvious aims of our existence. It will be the end of the dark ages.” Doyle is, of course, referring to spiritualism, and the experiments in connecting with spirit forms that occupied his mind obsessively towards the end of his life.

Even more eye-opening is a letter from Lewis Carroll, written on Christmas Day 1893 to a Mr Butler, the father of Olive Butler, one of the many “child-friends” who were at the centre of his emotional life. Carroll has already given Olive Volume 1 of his book, Sylvie and Bruno and wanted to give her Volume 2 – but Olive’s parents, evidently suspicious, have decided to end their relationship. His letter is plaintive: “My dear Butler, This is to explain an (apparent) liberty which I propose to take this week, in sending Olive a copy of Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. Without some explanation, it might look like a sort of ‘feeler’ towards renewing negotiations as to being allowed to try to establish a friendship with her. So let me assure you that I have no such idea… But I think it would be a great pity, for no better reason than that you and I hold different views as to the expediency of friendships between old gentlemen and young ladies, to leave my gift incomplete.”

A whiff of paedophilia has, of course, hung around the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland for many years, although, as the TLS recently reported, “there is no evidence that he pursued the girls with anything other than his camera or with jocular letters”. But this letter seems a masterclass in creepy self-exculpation. (That word “feeler” has a creep factor all its own.) Even the handwriting is full of insinuating curlicues, the calligraphic equivalent of a children’s entertainer. The letter is going for £6,250.

The pièce de résistance of the fair’s correspondence, however, is a cache of 200 letters between George Orwell and the publisher Victor Gollancz. There’s a scratchy exchange about Animal Farm, first published 70 years ago. In a letter dated 19 March 1944, Orwell’s nervousness about submitting his anti-Soviet fable is apparent: “I have just finished a book… It is a little fairy story, about 30,000, with a political meaning. But I must tell you that it is – I think – completely unacceptable from your point of view (it is anti-Stalin)… If you think that you would like to have a look at it, in spite of its not being politically OK, could you let either me or my agent know?” The single-spaced typing reeks of worry that he’s gone too far and Gollancz’s reply confirms it: “Here is the manuscript of Animal Farm,” he wrote to Orwell’s agent. “I am highly critical of many aspects of internal and external Soviet policy: but I could not possibly publish a general attack of this nature.”

It’s piquant to discover the great polemicist becoming the first known writer to worry about being politically incorrect; and to find Gollancz unable to see Animal Farm as an attack on all totalitarian governments, not just the Soviets.

The Orwell letters are for sale as a complete archive by Jonkers Rare Books at Stall C09 for £350,000.

It is not difficult to see why there should be a renewed interest in letters. A century ago, the families of famous writers and politicians would keep their deceased relatives’ correspondence with the powerful, and sell them to book dealers for a few guineas. Fifty years later, when handwriting had partially yielded to type, letters featuring the inky scrawl of George Eliot or Graham Greene commanded high prices. Since email sounded the death knell of the letter in the post, these missives offer more than quaintness; these scribbled, un-wordprocessed outpourings are like dispatches from a lost civilisation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments