My Family and Other Animals 60th anniversary: Gerald Durrell's book is a triumph of conscious craft

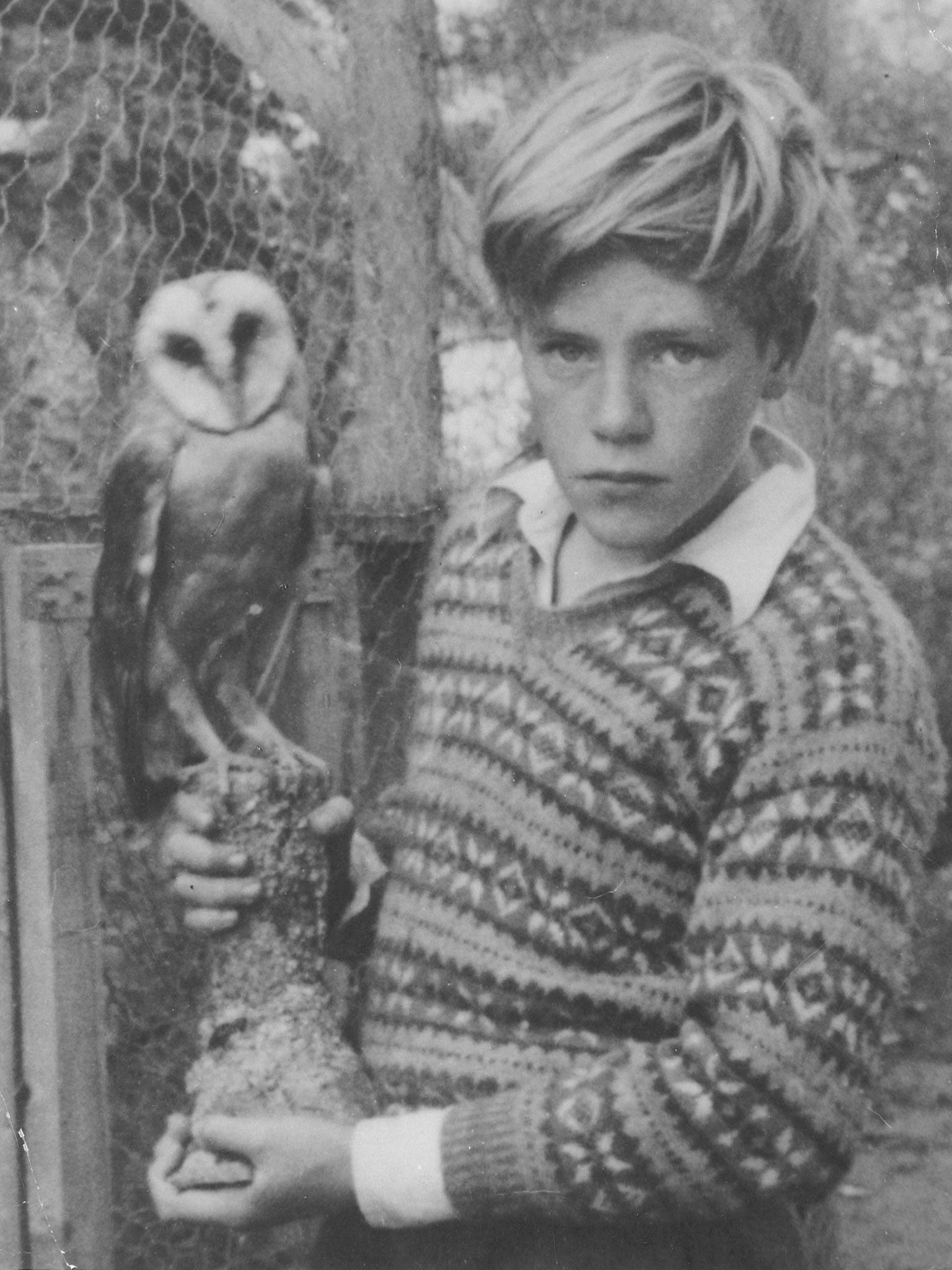

He was the father of conservation whose memoir of a childhood on Corfu became a classic. As ‘My Family and Other Animals’ turns 60, Simon Barnes celebrates the extraordinary Gerald Durrell

Gerald Durrell was a man of paradise. Paradise found, paradise lost, paradise regained, paradise destroyed, paradise dreamed in a vision of hope, paradise under siege, paradise relieved, paradise unattainable, paradise built with his own hands. Paradise was his business, his life, his destroyer, his salvation.

He produced a literary masterpiece that remains the finest evocation of paradise ever written. He built a paradise based on his own beliefs of what a zoo should be. And after his death in 1995, he left behind an organisation that works to restore a touch of paradise to humanity and to everything else that lives. "The world needs Durrell," says Sir David Attenborough. Durrell is a voice, an example, a legacy, a belief, a cause. And while his message has never gone away, it will be proclaimed with renewed power in 2016.

Next year it will be 60 years since the publication of Durrell's greatest book – My Family and Other Animals. It has sold millions of copies worldwide, and across the decade's generations of schoolchildren have grown up with the story of the Durrell family's stay on their paradise island of Corfu in the five years leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War. And to mark the anniversary of the book ITV will next year broadcast a drama series called The Durrells, based on that same impossible experience of paradise. A big Gerald Durrell moment is upon us, not least because the work of the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, which he founded in 1959, is more important than ever.

The focal point of the Trust is a wildlife park – always envisaged by Durrell as "a stationary ark" – that operates on Jersey, where his widow Lee still lives in the house she shared with him, working as the Trust's honorary director.

She was just 29 when they married, in 1978; Durrell was a damaged visionary of 53. They met while she was studying communication in lemurs, which made her doubly irresistible. Durrell later wrote to her from Jersey: "Darling, I want you to be an important part of every part of my life, and I want you to feel that at all times this place and what it does in the future is just a much your place as mine."

"The instant I met him it was as if a 1,000-watt lightbulb had been switched on," Lee, who is now 66, says. "The power, the energy, the charisma – you knew at once that you were in the presence of someone." The Jersey project, she says, "felt like a pretty enormous undertaking, but I went into it with my eyes wide open. I knew that I was taking on a man and his vision, and these things really couldn't be separated. And I wanted to do it with him."

Durrell died 21 years ago. He wrote more than 40 books, most of them overflowing with light and life and humour and joy. He was a man who knew black despair and breakdown but went on to find redemption. He was a man ahead of his time; all conservationists are agreed on that. He was the first person with a large public following to make the extinction crisis plain. But he preached not doom but action. He wanted the world to understand that practical conservation is the essential task of humankind – as essential for humans as it is for other animals. "People think I'm just trying to look after nice fluffy animals," Durrell said. "What I'm actually trying to do is stop the human race from committing suicide."

Durrell's best book is part of the language, part of the way we think. The broadcaster Clare Balding applied a neat twist to the title when she named her own childhood memoir My Animals and Other Family; being a well brought-up girl, she asked Lee's permission to use it.

Of course when you bring together the words Durrell and literature, most people – of a certain age – assume that you're talking about Lawrence Durrell. This is Gerald's older brother, author of the "Alexandria Quartet" series of novels. Lawrence – Larry in the Corfu books, 13 years Gerald's senior – had a huge success with it. The Quartet caught the wave of the 1960s to perfection and it was accepted that the family contained one great writer with works for all time, and another who wrote relatively ephemeral stuff that was entertaining, even thought-provoking, but very much a work of its time. I think that view is 100 per cent correct – except that the world got the brothers the wrong way round.

It was the great American scientist and science writer Edward O Wilson who coined the term biophilia: for the human affinity, the human need for non-human life. Everyone who has ever patted a dog or smelled a rose understands that. My Family and Other Animals is the greatest expression of biophilia in literature. Here is a boy in paradise, surrounded by an eccentric loving family and by the wonderful beasts of the Mediterranean islands. Here the young Gerry kept owls and pigeons and tortoises, witnessed a battle between a praying mantis and a gecko – above, on, and finally in his bed. One day his magpies – the Magenpies – got loose and trashed Larry's room and all those pages full of deathless prose.

Joy is at the heart of everything that Durrell wrote, but most especially it is at the heart of My Family and Other Animals. Here is a book that celebrates the wild world more thoroughly and more vividly than anything else ever written. It is at the same time funny and deeply serious; and it is a poor person who believes that humour compromises seriousness. It has reached people and moved them to laughter and other emotions, all them deep, powerful and packed with meaning. It has been a set book for exams and it has taught the joys of reading along with all the other joys. The book tells us that we humans are not complete alone: that without the wild world we are less than ourselves.

That wonderful title is a good joke, and so much more than a joke. We need to look after the planet for the sake of our species and other animals: because without them we're no good. Durrell – the man and the organisation both – are still telling us that same old truth and it's as vivid and as vital as ever.

My Family reads like a great gushing flow of spontaneous recollection, but in fact it is a triumph of conscious craft. Durrell began the book with five bestsellers already on his CV and he set down to write it in the certain knowledge that this was the best material he would ever have. It was the one book he enjoyed writing.

It is built on a complex and brilliantly managed structure. The human characters leap from the pages like caricatures drawn by an unusually knowing child. In history, brother Larry lived apart from the family with his wife Nancy; for literary purposes he is moved back in while Nancy is written out. Corfu is bounding with the life of humans and other animals: and so it becomes all islands. It becomes every golden age, it becomes paradise.

And that vision of a paradise shared by human and non-human animals drove everything Durrell ever did. The idea that human lives are dramatically impoverished in the absence of the natural world is now supported by findings on medicine, sociology, psychology, urban planning, child welfare and even crime statistics.

Durrell was conscious of loss all his life. The fact that wonderful things can be taken away forever was something that defined him. His early understanding of extinction was an aspect of that. "The world is as delicate and as complicated as a spider's web," he wrote. "If you touch one thread you send shudders running through all the other threads. We are not just touching the web. We're tearing great holes in it."

"He was a man who knew about despair," Lee says. "He had an apocalyptic vision of the world, and the destruction, stupidity and greed caused him very deep distress, and it was the reason for the drinking." At one stage a doctor rather rashly recommended Guinness to improve his physical condition. Durrell took it on manfully, usually as breakfast.

Most writers who create a masterpiece and a series of bestsellers are content to leave it at that. Not Durrell. Durrell had to save the world as well, and he did a pretty good job of it in the circumstances. But it cost him. Despair, breakdown and a busted first marriage: he went through > the soul-deep struggles that often tear exceptional people in half.

Durrell recovered thanks to his second marriage, with Lee. "He found hope in the small victories, as we do in the Trust today," she says. "I've just heard from one of our former keepers who runs an orangutan conservation project in Sumatra. He has won a major court case against a company illegally clearing land and planting oil palms. It's another small victory."

Zoos can and should be about the informal education of the public, but Durrell always saw a bigger role: as a centre for science-based education in conservation. He was in Mauritius on a conservation trip in 1978 when he said to his assistant John Hartley: "I've often talked about turning the Trust into a sort of miniature university of conservation, and when we see the minister this morning I am going to offer him a scholarship for a young Mauritian to come to Jersey for training."

Hartley was aghast. He pointed out that they had no facilities for education, nowhere for students to stay and no plans in place. Durrell told him airily: "Your trouble is that you always get bogged down in the minor details of life. I feel sure that you will be able to solve all those problems."

He did, they did, the Trust did. The Durrell Conservation Academy on Jersey has being going for 25 years, and has 5,000 graduates from 139 countries. People come to Jersey to work because they want to spend their lives in conservation. It's been said – though it's been said of many other things on the Durrell CV – that this was the best thing he ever did.

There was an occasion early in the Academy's history when the students were taking a break from their studies. "It was a perfect moment," Lee remembers. "Gerry had tears in his eyes when he said to me, 'I never believed I would be playing croquet and taking tea with 10 conservationists from 10 different countries here on Jersey'."

The Trust continues its work: trying to integrate the wildlife park, the needs of the paying public and the conservation activities that take places across the world – in Mauritius, Madagascar, the Caribbean, India and Brazil. These are complex times, and the virtues of captive breeding and assurance populations are no longer universally accepted. The Trust attempts to adapt to changing needs while staying true to the original vision.

"Perhaps the one thing that has changed and the one thing that would have given Gerry delight is the knowledge that he is no longer alone," Lee says. "For years he felt that he was the only one who saw what was going on and who was trying to do something about it. But now there are conservationists who share his vision. The world is now full of people who believe what Gerry believed."

The organisation is inspired by the past but not stuck in it. Earlier this year I attended the annual gathering of the home and overseas staff for the Conservation Workshop, where they exchanged experiences and methods and successes and the occasional failures. They discussed pygmy hogs in India, ploughshare tortoises in Madagascar, Darwin's mangrove finches in Galapagos, the world's rarest snake (the St Lucia racer), and two critically endangered species of fruit bats.

The occasion fizzed with ideas and challenges and it all took place in a mood of seriousness and intellectual depth leavened with banter, an atmosphere in which dedication and knowledge are taken for granted. Durrell the man would have been delighted by the vibe, and doubly delighted that it was all happening without him needing to power it.

In 1988, they buried a time capsule in the park at Durrell. It contains a letter to the future, written by him. It concludes: "We hope that there will be fireflies and glow-worms at night to guide you and butterflies in hedges and forests to greet you. We hope that your dawns will have an orchestra of birdsong and that the sound of their wings and the opalescence of their colouring will dazzle you. We hope that there will still be the extraordinary varieties of creatures sharing the land of the planet with you to enchant you and enrich your lives as they have done for us. We hope that you will be grateful for having been born into such a magical world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments