OCD and the graphic novel

As a medical student, Ian Williams' life was bound by the obsessions and rituals of OCD. But it was many years before he found the courage to get help. Now, his graphic novel offers a window on his tortured secret world

The young man tells me that he is having trouble leaving his flat. Every time he goes out, he starts to worry that something dreadful will happen to his family. A calamity might occur, he feels, if a car with a 4, 9 or 6 in its registration number passes as he closes the door. It is a busy road and he is compelled to check every number plate.

If he spots an unlucky one, he has to go back inside and perform a protection ritual. The process often involves him crossing and re-crossing the threshold repeatedly. Thresholds are where bad luck gets in.

He did not confide in me on first meeting: he realises how "mad" he sounds and has no desire to be "sectioned under the mental health act". Over a series of consultations for minor ailments, he has tested the waters by hinting at his odd preoccupations, while resisting further inquiry. Finally, he has decided that I am to be trusted. His disclosure strengthens my suspicions that he is suffering from a form of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

I ask him some more questions to confirm my diagnosis and then tell him that the prognosis is pretty good: the condition is treatable with talking therapies and with medicines. He seems monumentally relieved. I ask whether he ever has thoughts of harming himself. Sometimes, he says, usually as a transient wish to escape his psychic torment.

He expresses mild surprise that I seem to "get" what is going on in his head. I have a strong urge to tell him that I understand exactly what he is going through, but I resist: I have rarely discussed my experiences as a young man, even with medical colleagues. In fact, I almost never discussed them with anyone before finding my voice through the medium of comics, in which I found a way to articulate my own earlier struggle with mental illness.

I remember, at medical school, drunken discussions concerning the small number of class "nutters" in our year of 150 students: the girl who had time off after being found wandering the city in her nightdress following an impromptu exorcism by a group of Christian students; the girl who starved herself into a walking skeleton; the reclusive boy who was a chronic hypochondriac. I kept quiet, but laughed along with the others. I was convinced that I, too, was doomed to a future as a "nutter", having developed some kind of "madness" that I was struggling to hide.

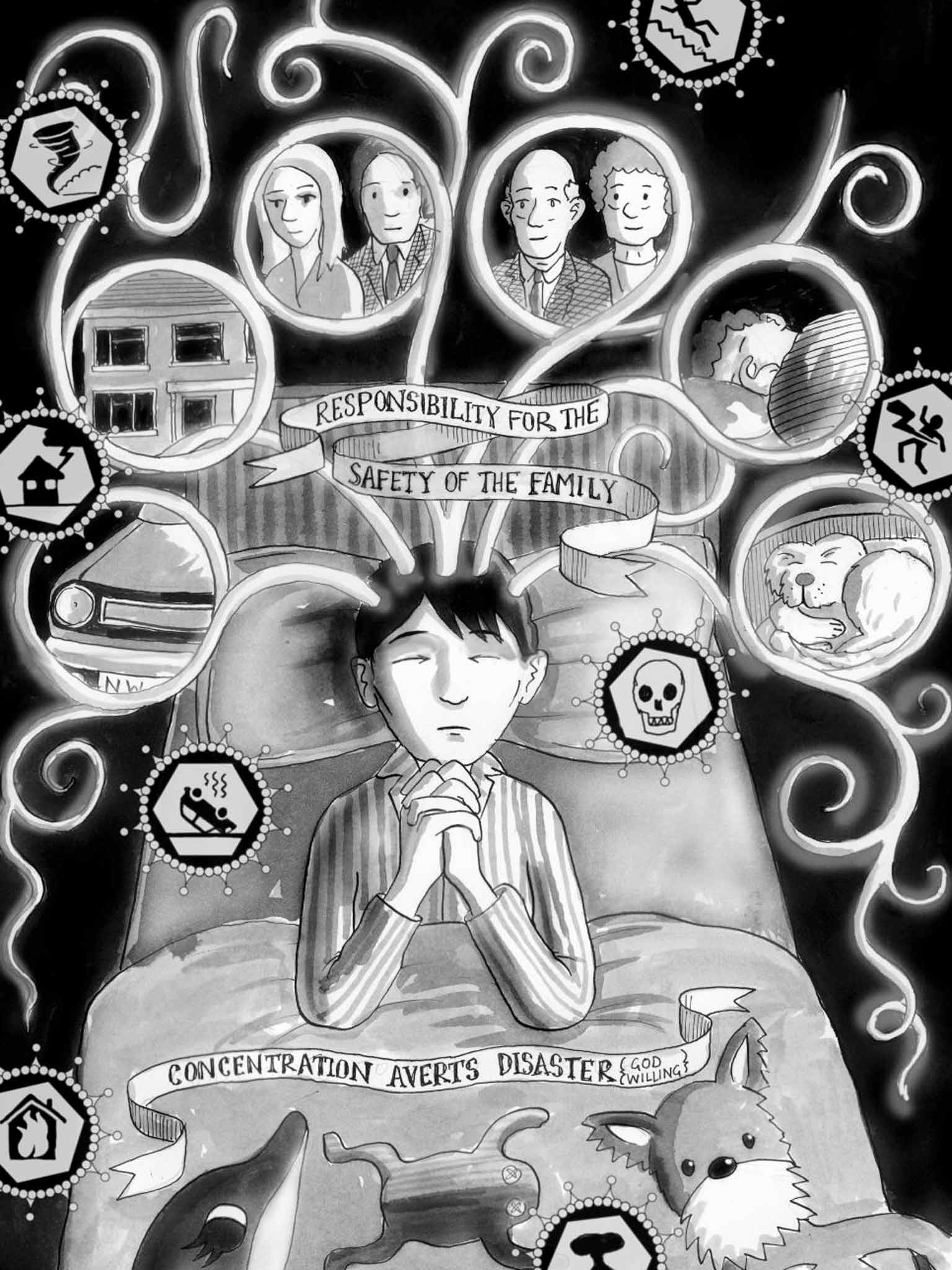

The bedtime rituals of a sensitive child had burgeoned, after puberty, into a complex ceremonial system, aimed at protecting those I loved from misfortune and evil. The obsessions of the OCD sufferer often mirror the moral panics of the time. The tabloid outrage of moral entrepreneurs in those pre-internet days would be shown by time to be largely unfounded: snuff movies, subliminal backwards song lyrics and satanic ritual abuse. Back in the 1980s, however, they fed my anxiety and convinced me that the pastel colours of the everyday world were but a thin veil drawn across a hidden, darker, reality.

I had not been brought up in a religious home and loved the ominous, power-chord riffing of metal bands like Black Sabbath. But a couple of coincidental events – my grandma having a stroke while I was at a rock concert, my mum narrowly avoiding a head-on collision while I was listening to a metal album – shaped my free-floating anxiety into a conviction that I was to blame and a phobia of the occult imagery used by metal bands as schlock entertainment.

The fear of causing harm to loved ones by inadvertently disobeying some cosmic decree worsened throughout my adolescence. I went to medical school at 17 and did my best to hide my mental distress. The new environment, free from the old triggers, did me good at first, but the frequent partying did not and, gradually, my obsessions returned. If I saw someone in a heavy metal T-shirt, for instance, or with black goth hair, or with a shaved head and goatee (the mark of a magus), I would feel spiritually contaminated and associate that street with bad luck.

Intrusive thoughts plagued me and the city became a psychogeographic map, full of taboo areas. I started to see occult symbols in the designs of buildings, carpets, fabrics and doors. I scraped along, terrified of seeking help, realising that something was seriously wrong with my thinking but knowing that if I was sent to a psychiatrist there wasn't a hope in hell that the fact would go unnoticed among my peers. Sightings of fellow medics among the patients were gleefully reported by medical students, the details gleaned from their medical notes.

After qualification, I ran away from the city to live in rural North Wales, where the triggers were fewer, and became a GP. I got fit, cut down on alcohol and focused my mind through adrenaline sports. Sick of being cautious, I now became obsessed with scaring myself stupid through rock climbing and mountaineering, hooked on the resulting endorphin highs. My mind settled, aided by the love of a good woman who, incidentally, loved metal. I started to listen to loud music again, catching up on all the albums I hadn't been able to listen to. I felt proud to have overcome the OCD without professional help, but my new-found freedom from torment left me restless and discontented, hungry for new adventures yet bound by a sense of responsibility. Periods of ennui and depression, recurrent since adolescence, still dogged me and, with money to pay for private therapy, I finally sought help.

Fast forward 20 years. I am writing and drawing a graphic novel about, among other things, a slightly discontented doctor who is treating a patient with OCD, thinking he can help him because he knows exactly how that patient feels. Although it is a work of fiction, I begin to wonder if, despite the long absence of bizarre and magical fears, my OCD did not disappear completely, but turned into something more subtle, to other subjects.

Doubts about my life choices, my career and my relationship replaced fears about malevolent external forces. I suspect that OCD might have shaped my life to a greater extent than I previously thought, making it difficult for me to settle; to feel content (I have left my quiet home in the mountains and moved back to the city). There again, maybe I am just over-analysing. What if I had had specialist treatment earlier? Who knows? I didn't seek it and it didn't happen, and my life feels fine. I feel like I am doing something of worth.

"Do you think I'll always be like this?" asks my patient. No, I tell him. You might always be a little obsessional. It might cause you occasional distress, but with help you can find ways of coping and of turning the creative energy it takes to create such a complex system of symbolism and warped logic into something more productive, and positive.

The Bad Doctor (Myriad Editions, £12.99).

twitter.com/TheBadDr

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks