Perry Pontac: A man of infinite jest

Not many of us have heard of playwright Perry Pontac. More's the pity, says Alan Bennett – his Shakespeare spoofs, now in print, are perfect parodies

The plays of Perry Pontac have been a well-kept secret on BBC radio for far too long. They have been turning up regularly on what I'm afraid I still call the wireless ever since 1987, but it's only with Codpieces, comprising three of Pontac's Shakespearean parodies, that they now at last find their way into print.

Parodies they are, but told in the form of prefaces and continuations: what happens after Fortinbras turns up at the end of Hamlet or before Lear takes it into his head to share out his kingdom? Say Romeo and Juliet didn't die, what is in store for them 20 years down the road? Pontac stands to the side of these familiar masterpieces, treating them with irony rather than disrespect and in language so close to Shakespeare's that it's a while before the penny drops and one realises this is parody of the highest order.

Now I am no stranger to Shakespearean parody, a sample of which was one of the highlights of Beyond the Fringe, the revue with which my career started back in 1960. And it was very funny, but reading Pontac's Shakespeare I am (only slightly) mortified to find that he can write cod Shakespeare much better than Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller, Dudley Moore or myself.

No one, though, can parody anything – an author, a composer, a singer, a style – without initial love and delight. Parody comes out of affection; it is an homage and the nearer a parody adjoins its object the better it is. Pontac would be Shakespeare if he could, so instead he simulates him so exactly that it's only gradually one realises how gloriously silly it is.

And it isn't easy. Peter Cook used to think he could extemporise Shakespeare, but it was always dire and indeed an embarrassment, whereas with Pontac one has to keep remembering this isn't the Bard, so close is the language to the real article.

Of the late Laertes, for instance:

'A corpse who even now

Is freshly festering in a nearby grave

With all the zest of youth.'

Or in Fatal Loins:

(The Nurse speaks of caring for Juliet's numberless children):

'I needs must groom their thickly knotted hair;

They scream at first, then smile to look so fair.

For combing is a kind of pleasant woe,

And parting such sweet sorrow. I must go'

Another prerequisite of successful parody is that the writer should know more than his or her audience... but only a little more. There would be no sense, for instance, in sending up Shakespearean sonnet forms to an audience unversed in them. Whereas an audience knows what Shakespeare sounds like without (and I speak from the heart) always understanding what is being said. And in that gap lies parody.

Pontac's fantasy is as exuberant as his language, with gender a mere trifle. The grizzled Kent reveals to Lear that he is and has always been, a woman, whereupon Lear falls for him on the spot:

'Kent: My voice was ever low

An excellent thing in woman, as you know.

And years of drinking sack and heavy mead

Have delved for me a deeper voice indeed.'

"All the fault of that damned padre" was Nancy Mitford's uncle Matthew's response when he was taken to Romeo and Juliet. He might well have preferred the Pontac version in which Romeo survives the tomb only to cherish a lifelong passion for the bumbling friar:

'Romeo: Thy tonsure – that sweet circle past compare,

Like a pink lotus in a sea of hair.

Thy noble ankles and the very toes

That peep out of thy sandals in neat rows'

Sublimely silly though they may be, Pontac's plays do have what are now quite venerable ancestors, with some of his wilder imaginings not unrelated to the kind of sketches that always used to be on in the West End when I was young – Sweet and Low, Airs on a Shoestring, Pieces of Eight – the kind of revues which, alas, Beyond the Fringe killed off. They have radio antecedents too as there are echoes here of the idiosyncratic comedy of Peter Ustinov and Peter Jones, In All Directions, in the early days of the Third Programme. Henry Reed is another forebear, the sagas of Hilda Tablet in the same strain of intellectual comedy. Though, of course, one must not say so... intellectual is not a word the BBC would welcome attached to comedy (or anything else much).

If I have a criticism (and I don't) it would be that Pontac occasionally permits himself a dreadful joke. But then so do I, so I'll keep quiet.

The plays printed in the book are only three of Pontac's large and varied output. I hope these will just be the first of many that will now find their way into print and that this may lead to their performance on the stage. So skilful and silly, they are a gift to actors and a tonic for audiences. Nobody else is doing this. They should be seen.

Fatal Loins: Romeo and Juliet reconsidered

CHORUS: Two households both alike in dignity,

A boy and girl by Fortune cursed and blessed,

A look, a dance, a kiss, a balcony,

A wedding, several killings, and the rest;

A tale of fatal loins and famous lines,

Of star-crossed lovers and inept divines.

But O! if stars like theirs could be uncrossed,

If grief converts to joy and gore to glory,

A message is delivered that was lost

Which alters the direction of our story...

If Juliet and Romeo survive,

Will their eternal passion stay alive?

***

FRIAR: And Juliet?

Art thou yet loyal to thy loving wife?

ROMEO: I am as ever steadfast unto her.

For witness thereof, I refer, good Friar,

To all the babes our loins have gendered forth

O'er twenty years of spawnage: Giovanni,

Renata, Octorino, Ferabosco,

Sylvestra...

FRIAR: Nay, no list I pray, for I

Have christened all, a dear and constant duty.

But tell me more, if more there be to tell,

Of shame or dark intent, of love denied

Or lust permitted, passions infamous,

Illicit tidings, secrets of thy soul.

... ROMEO: (With difficulty) I love her not. No longer doth my heart

Sing sonnets at the altar of her eyes.

She is much changed. Hast thou perceived it not?

FRIAR: She is a lady pious as a nun.

ROMEO: And vast as a cathedral, holy Friar.

FRIAR: 'Twas bearing thy prodigious progeny

(Sweet gurgling girls and boys of every age)

That hath enlarged her to her present bounds.

ROMEO: Should she not thereby grow the smaller? No.

The more she doth produce, the more she is,

For both are infinite.

FRIAR: Confess, my son,

Is there another that thou favourest?

ROMEO: Truly I have been tempted, gentle Friar,

Even to the port and harbour of the act.

FRIAR: By one alone, or by a vast array?

ROMEO: By one...that I have known these many years...

FRIAR: One thou knew ere thou met Juliet?

ROMEO: Yes, Friar Laurence.

FRIAR: Then it Rosaline is –

She that thou spurned to marry thy sweet bride.

I see it in thine eyes. It blazeth forth.

ROMEO: (Much moved) O Friar Laurence, cease! I cannot speak.

My heart is in my mouth.

FRIAR: Then set thy mouth

Within thy heart that it at last may tell

The story of its passion.

(Pause)

ROMEO: (Suddenly) O 'tis thou!

'Tis thou, dear Friar, 'twas ever ever thou!

Thy noble qualities have long seduced

My heart and senses to a love of thee...

FRIAR: (Horrified.) Fie! Fie! For shame, good Romeo, speak no more!

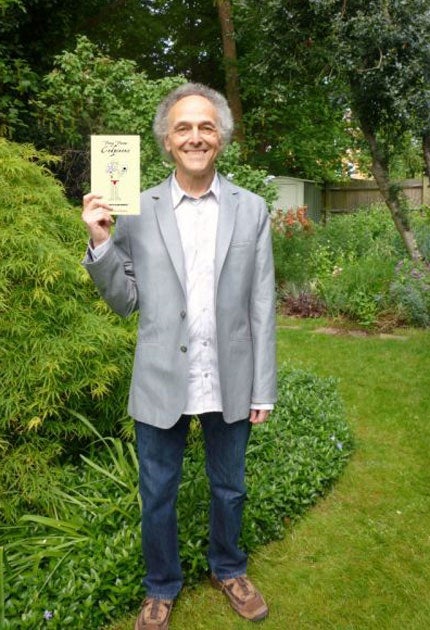

'Codpieces' by Perry Pontac, with a foreword from Alan Bennett, is published by Oberon Books ( www.oberonbooks.com, £9.99)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies