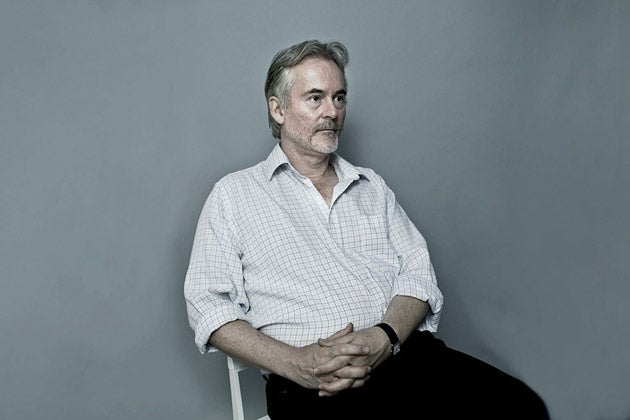

Secrets and lies: Martin Sixsmith on the trail of a boy ripped from his mother

The truth is important to the former BBC news reporter and government press secretary Martin Sixsmith. Luckily, he didn't need to dress up the remarkable true story told in his latest book...

You're a journalist, aren't you? I've got a good story for you." Such instant recognition is one of the hazards of being a former high-profile TV reporter, and Martin Sixsmith's face – set against the skyline of Moscow, Washington and Warsaw – is familiar to anyone who watched BBC news bulletins in the 1980s and 1990s. Another pitfall is that the proffered story in such situations rarely lives up to its billing. But in the case of Sixsmith's encounter at a New Year's party in 2004, it did – and spectacularly so, since it was the inspiration for his latest book.

"It was one of those coincidences that nudge and deflect our life trajectory," muses the 55-year-old, who, after he quit the BBC in 1997, worked as director of communications for a series of Labour ministers including, Harriet Harman, Alistair Darling and Stephen Byers, until a headline-grabbing falling out in 2002 with the latter over the activities of the special advisor Jo "a-good-day-to-bury-bad-news" Moore. "That New Year's party," Sixsmith continues, "was a small example of chance intervening. The book itself tells a story with a much bigger example of the same thing."

Sixsmith found himself talking to Jane Libberton, whose mother, Philomena, had recently revealed to her that, in 1950s Ireland, when young and unmarried, she had given birth to a son, looked after him for three years, but been forced by nuns to give him up for adoption to Americans. For almost 50 years, she had kept this secret from Jane and the rest of the family she had subsequently raised in England, until she could no longer bear the pain of remaining ignorant of her first born's fate. She wanted someone to help her find out what had happened to him – and Libberton wondered whether Sixsmith would take it on.

He said yes, and The Lost Child of Philomena Lee is his account of how this victim of Catholic Ireland achieved some sort of closure. Sixsmith doesn't tell it, as might be expected, as a detective story. Instead he opts for a hybrid: part fiction – reconstructing scenes and conversations – and part fact. The political and social backdrop of the illicit trade in illegitimate children between Ireland and America is thoroughly explored. No names have been changed and no blushes spared, not least those of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, who had repeatedly refused over the subsequent decades to help Philomena contact her son.

"I made a conscious decision to keep myself out of it," says Sixsmith. "I thought that writing it as a description of my investigation would be a bit too intrusive and detract from the real story of what happened to Philomena." We are sitting in the front-room of his mews house in Knightsbridge, near Harrods, and there is a certain irony in the fact that, outside the window, is the façade of a church building – though Sixsmith points out with typical fairness that it is German Lutheran and therefore not responsible for the particular sins we are discussing.

That anxiety to present a rounded picture and leave readers to draw their own conclusion – "ingrained BBC", he jokes – shapes Sixsmith's telling of Philomena Lee's story. There is none of the emotion and outrage present in, say, Peter Mullan's 2002 film on a similar subject, The Magdalene Sisters. "I kept it low-key and cogently argued," he insists, "because I felt the facts speak for themselves. The debate about all of these revelations has been very emotional in Ireland and I didn't want to feed into that hysteria."

Such restraint stretches even to the moment when Philomena finally, with Sixsmith's help, discovers that the son she named Anthony grew up in America, as Michael Hess, to become a successful lawyer, rising to be a senior official in the Reagan and Bush Sr White Houses. But Hess was also leading a closeted gay life, fearing that his Republican colleagues and Catholic adoptive parents would disapprove, and died in 1995 of Aids.

Did Sixsmith have any qualms about laying bare Philomena's life, and her grief, when she is still very much alive and kicking at the age of 76 in St Albans? "She wanted to see the story put in a proper context – that she isn't a fallen woman; that she isn't a sinner. She apparently didn't even know, when she slept with the father in Limerick in 1951, how babies were made. And I can so believe that, because she had been in a convent school and the nuns never told the girls anything about sex."

Sixsmith is making the whole researching and writing process sound pretty straightforward but there must, I suggest, have been tricky times, working on a project that touched so directly on hypocrisy, guilt and secrets. "I did worry," he admits, "that Philomena would be upset when we found out about Michael being gay, but she wasn't. She's remarkably unbitter about things. If it had happened to me I would bear remarkable bitterness in the depths of my heart about the people who had treated me that way, but she doesn't. She stopped going to Mass for a long time but recently has started again."

Blurring the line between fact and fiction is currently very fashionable. Me Cheeta: The Autobiography and Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall caught the eye of this year's Man Booker judges, and even the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore is said to be writing his new biographical work as a novel. And that dancing around the distinction between the two genres has been the hallmark of Martin Sixsmith's publishing career since he left government service. His first novel, 2006's Spin, was set in the near future but read for many like an account of life with Byers, Moore, Alastair Campbell et al.

"It was grand guignol really," he protests. Sixsmith has steadfastly resisted Spin being recategorised as memoir – as have his publishers' lawyers. "Everything in it is so exaggerated that it becomes innately ridiculous and unbelievable, but always with that sense that actually this was the way things were." Fact or fiction, its publication led to a sideline for Sixsmith as a consultant on The Thick of It, the award-winning BBC political satire set in the inner workings of government.

His earlier remark at Philomena Lee's lack of bitterness prompts me to wonder if he still feels bitter about being first sucked into, and then spat out, by the New Labour news management team. "I regretted it for about six months, when the government was insisting I was wrong and they were right. [In 2002, the Transport Secretary Stephen Byers announced that both Sixsmith and Jo Moore had resigned, but Sixsmith contradicted this and said that his exit had been forced.] That was a tough time, but in the end they 'fessed up, paid me a lot of money and made a public apology." It also ended Byers' ministerial career.

"You can take the cynical view of ministers," Sixsmith reflects, "that they are only interested in themselves, or you can take the view that they do actually want to make changes that benefit people. Some are in the first category and some in the second. Alistair Darling is undoubtedly in the second. He is the absolute epitome of a Presbyterian Scottish bank manager whose head is not turned by power." And the first category? "Stephen Byers." The two are not, Sixsmith confirms, on Christmas-card terms.

It was the idealism of New Labour that persuaded Sixsmith to abandon his BBC career in 1997. With the government now so low in the polls and so unpopular, does it feel like a sacrifice in vain? "There is sadness at seeing how that high idealism I shared was thrown away. I may be blinkered but my feeling is that it happened because they couldn't stop themselves telling lies. New Labour was enthralled by the spin-doctors who got them elected. They developed this attitude that if we say black is white, then you will believe black is white." But wasn't he a part of the spin machine too, as a government director of communications? "No," he replies firmly. "I was in civil service. Alastair Campbell and Jo Moore and all these special advisers were there to promote their ministers. They were on the other side."

Sixsmith's experience of New Labour seems to suggest that political power inevitably corrupts those who hold it, even while they still believe they are acting morally. Perhaps the same excuse might be offered for the actions of the Catholic Church in the Ireland of the 1950s when they dealt so harshly with Philomena Lee and her son? Sixsmith pauses for a moment. It is clearly a tempting and easy analogy, but he is an old-style BBC man to the end. "That might be stretching it a bit," he simply but firmly replies.

The extract

The Lost Child of Philomena Lee, By Martin Sixsmith (Macmillan £12.99)

'... Philomena wept. She was distraught. She blamed herself for not speaking about Anthony earlier, while he might still have been found. It was hard to know what to say to a mother who had lost her child not once but twice. "You mustn't blame yourself," I said a little lamely. But she did...'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments