Staring back at depression can leave the reader uplifted; Week in Books column

When Franz Kafka’s travelling salesman wakes up late one morning transformed into an insect, his family (and boss) banging at the door for him to attend to his duties at the office, we understand Gregor Samsa’s “malaise” to be socially induced, a tyrannical force insisting on nine-to-five normality that has turned him into something smaller, more scuttling, than he is. The Metamorphosis’s metaphor reflects capitalism’s dehumanising effects on the soul. Existential angst is also what we call it, though it could just as well be – as Matt Haig argues in his excellent new book – a sign that Gregor is very, very depressed. So depressed he can’t get out of bed, face his family, or feel like a functioning human being.

Haig’s theory has me wondering which of literature’s other great “misfits” might be suffering from some form of serious depressive anxiety or OCD. Heathcliff’s “brooding” could definitely point towards something graver in Wuthering Heights as could Holden Caulfield’s teen anomie in The Catcher in the Rye; Dostoevsky’s underground man is clearly grappling with phobias (agoraphobia? Hypochondria?) in Notes from the Underground as are many other anguished men of Russian literature. And women too, if we take the suicidal Anna Karenina into account. For more recent examples, John Updike’s Harry Angstrom, Paul Auster’s socially anxious men in The New York Trilogy, Dave Eggers’ own travelling salesman in A Hologram for the King. These characters seem shut off, hopeless, in a state beyond real human connection or fellowship.

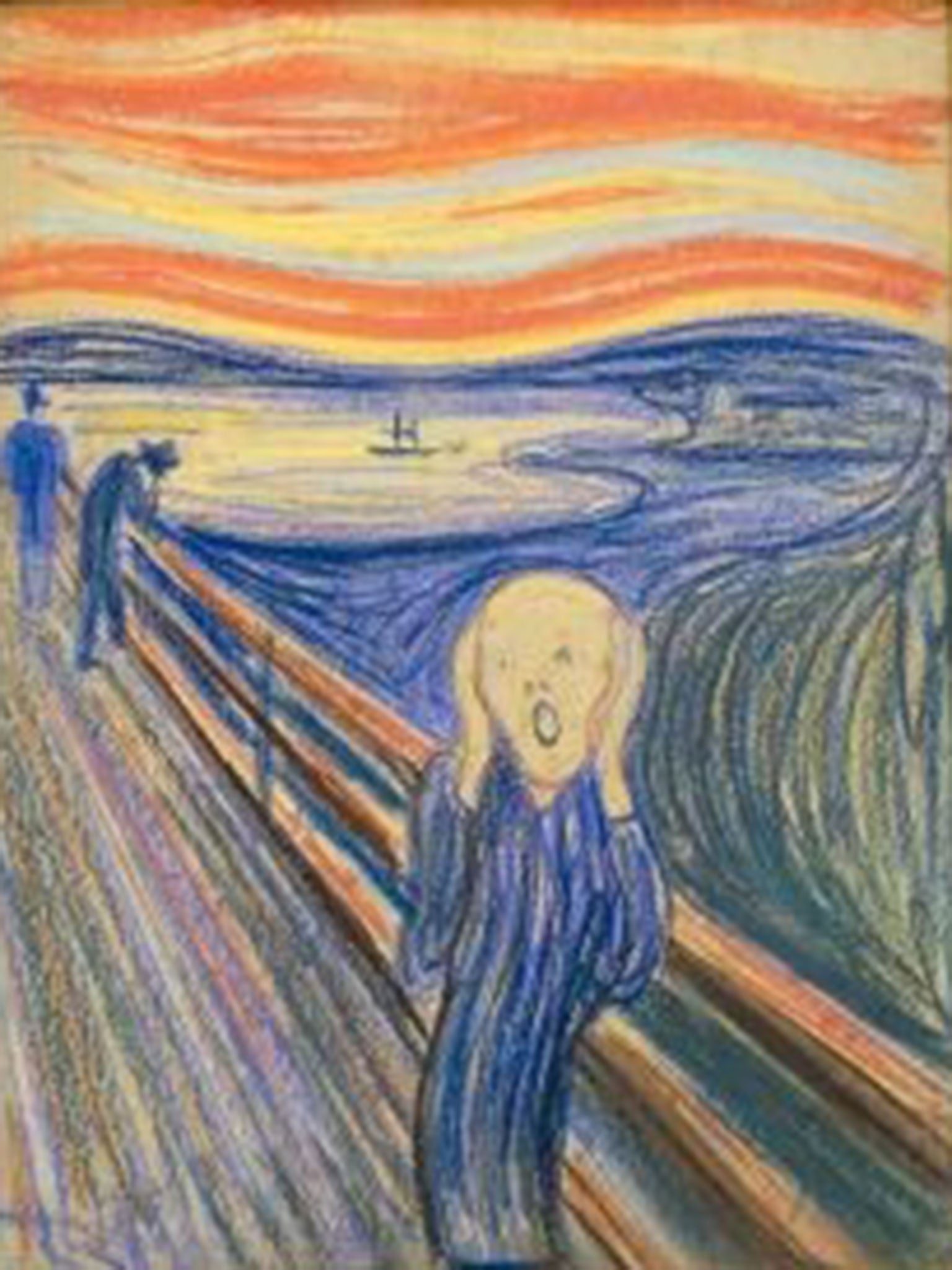

Their thoughts and actions reflect serious signs of depressive illnesses that we more commonly interpret, in literature, as “the human condition”. Except, in life as in literature, we choose not always to name depression as a facet of our humanness, or even of too much humanness, as Haig suggests, with reference to his own struggles and narrowly averted suicide in Reasons to Stay Alive, published this week. Despite the recent statistics on suicide – especially the rise in male deaths – depression is still being dismissed by some as a woolly imbalance, too unsubstantiated to be a proper illness like cancer or heart disease, or it is swept under the carpet. The taboo around mental illness applies to depression too, despite the fact that many – most? – will suffer a few bouts in a lifetime. It is not surprising that once you start looking, literature is full of deeply depressed souls.

This is not to mistake depression for Depression, where the former is part of the human condition while the latter is a life-stopping illness whose onset might have no apparent reason. And then the in-between, grey zone. Discussions around illness are not without their own contentions. Virginia Woolf suggested, in her writing, that her bouts of illness opened a door to greater truths: pain became a channel for Delphic illumination, in a sense. Barbara Ehrenreich undercuts this theory of illness with her book on cancer, and what she feels to be bunkum mythologies around suffering. Fast forward to Haig and he seems to say both that debilitating depression in his early twenties threw into sharp relief life’s deeper truths – “it reveals what is normally hidden” – and that it made his life almost unliveable. What’s striking is the uplifting experience of reading Haig’s book in the same way that Albert Espinosa’s bestselling memoir of cancer, The Yellow World, or Naoki Higashida’s reflections on autism, The Reason I Jump – or Anna Karenina – leaves us invigorated. The darkness lurking around or within which Nietzche describes as the abyss doesn’t seem half as horrifying when we stare back at it.

Can ‘pay what you want’ scheme work for small publishers?

A small New York publisher, Brooklyn Arts Press, is using a “pick your price” model to sell physical copies of books beginning with Noah Eli Gordon’s poetry collection,The Word Kingdom in the Word Kingdom. They are being compared to Radiohead who did something similar in digital. The publisher is hoping that word-of-mouth, and the quality of the book, will boost sales and it’s apparently working. I can believe it. The only “pay what you want” scheme I’ve encountered is the one used by taxi drivers in Lahore who implore you to pay, or not to pay – whichever you like – what you think the ride’s worth. It gets you thinking. How many of us would think a new book worth 99p if it wasn’t being offered to us at that price? It worked for Radiohead because of their fame and fanbase. Let’s hope it works for younger, newer talent too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks