Wanted: Chauffeur to deliver Allama Iqbal to the English reader: Week in Books column

Outside regional hero worship, few non-academics have heard of Pakistan's national poet

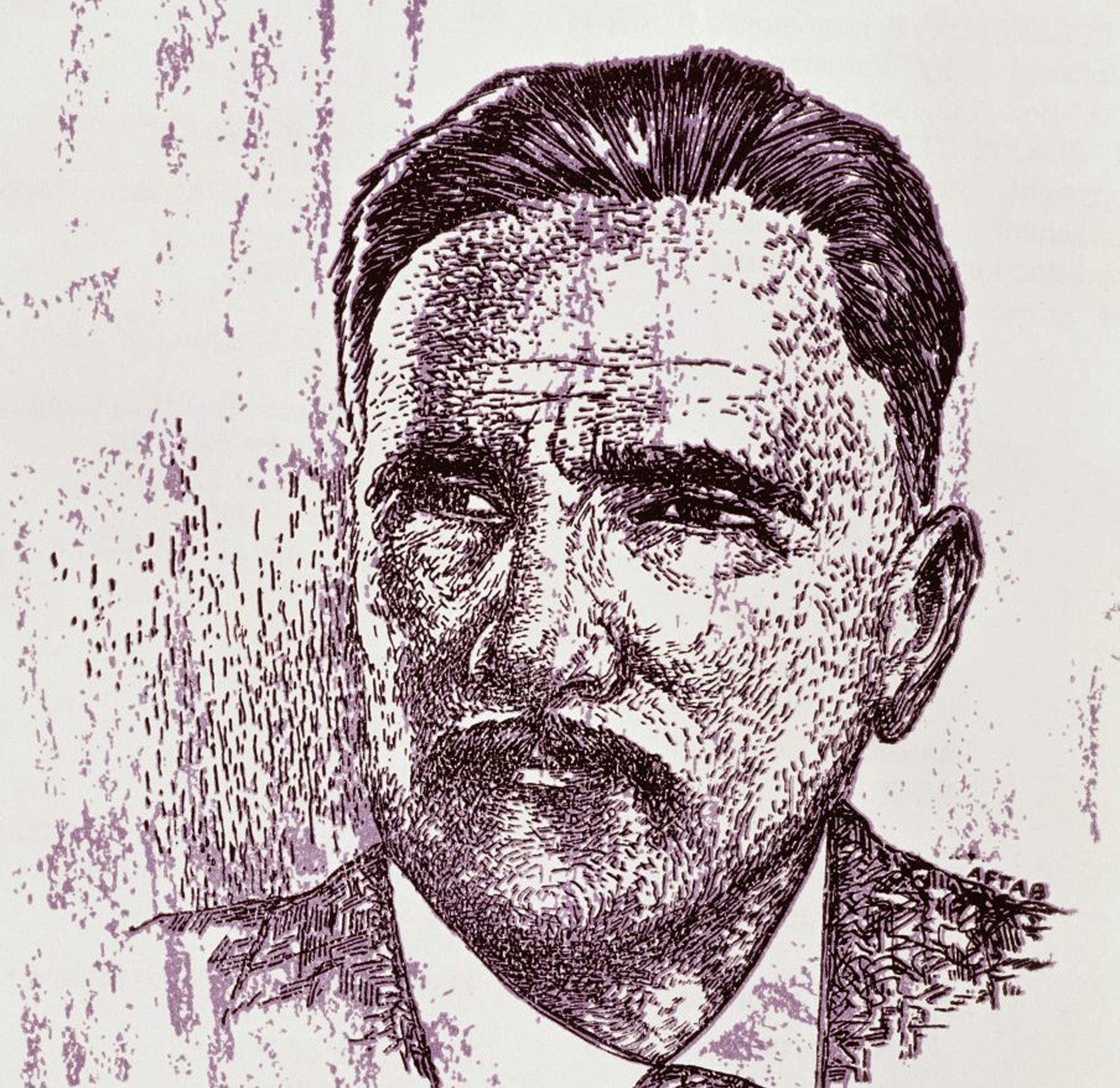

Who was Allama Iqbal? He was - and still is - the national poet of Pakistan, so revered that his birth date is marked by a national holiday.

Generations of children grow up reading – more often singing – his Persian and Urdu lullabies and rhymes. Students read his philosophical and political lectures on nationhood and identity at school. Afghans and Iranians call him Iqbal-e-Lahori (Iqbal of Lahore) and appreciate the daring and passion of narrative poems such as "The Complaint" (1909) – which directly interrogates God about the fate of Muslims, with the possibility that God might partly be responsible for their downfall. And generations of ordinary people – including those who can't read – listen to his words musicalised in "qawwali" form. His work is widely translated in Hindi and Malayalam for Indian readers, as it is in the Arab world.

Yet outside this regional hero worship, few non-academics have heard of Iqbal. EM Forster was said to be astounded by the fact that the West remained in darkness about the genius of the Indian poet, who became, posthumously, the symbolic figurehead of the Pakistani separatist movement that led to Partition in 1947. How is it that Tagore is known in the West and Iqbal isn't? It's a discussion begun at the inaugural Bradford Literature Festival last week, in a stirring talk on Iqbal, and that continued into the mid-week excitement around László Krasznahorkai, the Hungarian Man Booker International prize winner.

Most of us can read works by international writers only if we receive their translated works, and the greatest poetry by Iqbal hasn't seen too much light in English. The reason, think some, is that he is simply untranslatable in this language. Aamer Hussein, the short story writer who spoke at Bradford, thought that while Tagore, with the backing of WB Yeats, "bawdlerised" his own work for the easy consumption of Western audiences, Iqbal did no such thing, although he was Cambridge-educated and wrote essays in English. The cadence and melody of his poetry, Hussein believes, doesn't preserve its artistry in English. Iqbal comes off better in Italian or French, he thinks, because of the affinities between Persian/Urdu and the Romance languages. Perhaps that's why he's popularly called Shair-e-Mashriq (Poet of the East).

The idea of untranslatability is a sad one. It suggests that something meaningful is not just lost in translation, but dissolved by it. The jury is out for me, though, after speaking to Krasznahorkai's translator, George Szirtes, who was rewarded alongside the novelist at the Man Booker ceremony on Tuesday night. He believes that while there is no such thing as the perfect translation ("the value and weight of things change from one language to another… Even if you go into a bakery and ask for bread in German and then in English…"), it is never impossible. Szirtes certainly had his work cut out for him, if we take the judges' verdict into account: "What strikes the reader above all [about Krasznahorkai's books] are the extraordinary sentences, sentences of incredible length that go to incredible lengths, their tone switching from solemn to madcap to quizzical to desolate … epic sentences that, like a lint roll, pick up all sorts of odd and unexpected things as they accumulate inexorably into paragraphs that are as monumental as they are scabrous and musical."

It wasn't easy for Szirtes, who has translated three of his books and is working on a fourth; it is "slow work", he says, especially when one sentence goes on for an entire chapter. And yet he does not believe in the untranslatable text. Some will face greater challenges – ironically it is the simplest of prose or poetry that can be the hardest to translate for him, and this chimes with Iqbal's work, which contains a beguilingly naïve quality and a profound complexity alongside it.

The translator is a chauffeur to the Great Text, he thinks, and it's a lovely image: the white-gloved, almost invisible driver, steering a beautiful text on its journey. Szirtes is clearly an excellent chauffeur. It's finding the right chauffeur for Iqbal and those other 'untranslatable' writers…

From the trial to the divorce, Man Booker Winner pays his dues

As winning speeches go, László Krasznahorkai's at the Man Booker international prize might have been one long, incantatory sentence in itself, giving thanks to those who are alive and those who are "no longer among the living".

"I give my thanks to Franz Kafka", he began, but soon got on to his publishers, Thomas Pynchon, William Faulkner, Dostoyevsky, Bach, Bob Dylan, Nick Cave, Jimi Hendrix. And most collegiately, both his first and second wives.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments