When the 'nanny state' ruled: Strange appeal of bossy ad campaigns from the 1960s and 1970s

The ads warned us against everything from dropping litter to venturing near water. Now a new book is celebrating them

In an original Keep Britain Tidy poster revealed in 1965, an enormous, admonishing finger –ostensibly a divine digit – is designed to inspire in the littering transgressor a sense of shame, guilt and fear. A classic example of how Britain's post-war public-information campaigns worked, it arrived at a time when the nanny in "nanny state" was arguably at her most terrifying.

Any child of the 1960s and 1970s will recall how this approach also manifested itself in the unsettling public-information films released by the Central Office of Information. Think of the figure of death waiting for a young "show-off or fool" to come a cropper in Dark and Lonely Water (1973), a stark warning to children against playing around water, or even the teleporting road-safety superhero, the Green Cross Man.

These were not so much benign nannies as omniscient watchmen – Orwellian Big Brothers who watched and judged our every move.

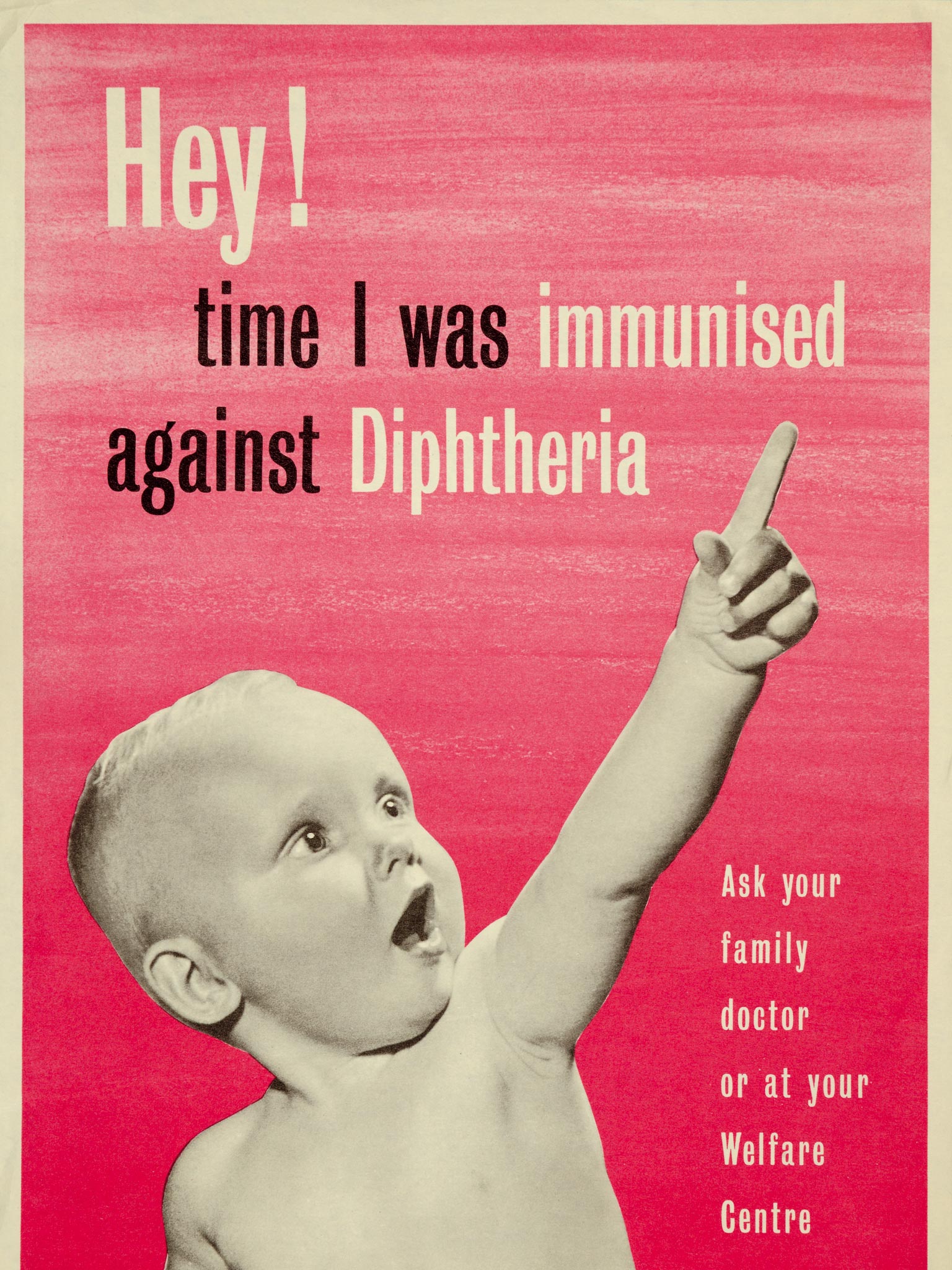

Similar images feature in Keep Britain Tidy: And Other Posters from the Nanny State by Hester Vaizey, a new book out on Monday that draws on dozens of examples from the National Archives. They warn us to, among other things, wash our hands before eating and always wear a bicycle helmet. The abstract, almost supernatural quality of some of these messages has fascinated me since my own childhood. I grew up in 1970s suburban Manchester in constant fear of messages like these.

Now a graphic designer and screenwriter, I started a blog last year about Scarfolk, a fictional town in which the terror in the warnings of my youth is exaggerated to darkly comic effect with the introduction of over-the-top supernatural or totalitarian elements.

In my post about the "we watch you while you sleep" campaign, I unearth posters and a film from the town archives that show how, in 1976, Scarfolk Council surreptitiously introduced tranquillisers to the water supply and employed mediums to creep into the bedrooms of citizens who were suspected of wrongdoing and record their dreams. Evidence they gathered would be assessed by a local judge who could hand out the appropriate punishment.

The blog took off and my own book, Discovering Scarfolk, is set for publication later this year. It will be a study in parody and absurdity, but I often find that I only need to nudge the original material to take it to its logical, warped conclusion. For years, government agencies warned us in deathly tones about the seemingly esoteric dangers of leaving bottled milk outside one's house, or placing rugs on newly polished floors. By the time the finger-wagging Keep Britain Tidy poster of 1965 was produced, the concept of the omniscient watchman was already ingrained in the public imagination, and not just because of religion. Second World War propaganda campaigns were the forebears of these public-information drives.

The "Careless Talk Costs Lives" series by the Punch cartoonist Fougasse depicts Hitler eavesdropping on private conversations. In each image, Britain's enemies are secreted into the background, in bottles or as wallpaper designs.

After 1945, in the absence of a tangible enemy such as Hitler, the idea of all-pervasive surveillance seems to have transferred naturally from the war (and later the Cold War) propaganda effort to public-information campaigns concerned with more quotidian issues. When the state asked us to adapt our behaviours around cleanliness, health and safety, family and work, it perhaps assumed that we would accept that the "ears" in the walls belonged to the state or society rather than a foreign enemy.

Messages such as these work because if an authoritarian presence – even a figurative one – can be invoked, people are more likely to respond. Stanley Milgram, the American social psychologist, showed this in his work on obedience. And more recently, Derren Brown entertainingly demonstrated the same idea in his 2012 show, Fear and Faith. Yet we now rarely see public- information posters or films of the kind created in the post-war period of paranoia up until the 1980s. With the exception of less nuanced warnings about drink-driving or smoking, the government has become noticeably muted on the subject of how we should conduct our day-to-day lives.

In 2011, the Central Office of Information closed its doors. Has the state stopped "nannying" us? Perhaps not. The omniscient watchman made an abrupt return last year. No posters or films heralded his arrival; it was the whistleblower Edward Snowden who alerted us to his presence.

Despite the absence of a public information campaign, and perhaps ironically, given the Government's tradition of warning us about all-encompassing surveillance, the NSA and GCHQ spying revelations have reminded us that we should be careful what we say because, online at least, the walls still have ears.

'Keep Britain Tidy and Other Posters from the Nanny State' by Hester Vaizey ,Thames & Hudson. £14.95.

Follow Richard Littler's blog at scarfolk.blogspot.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments