Who chooses the set-texts our children study?

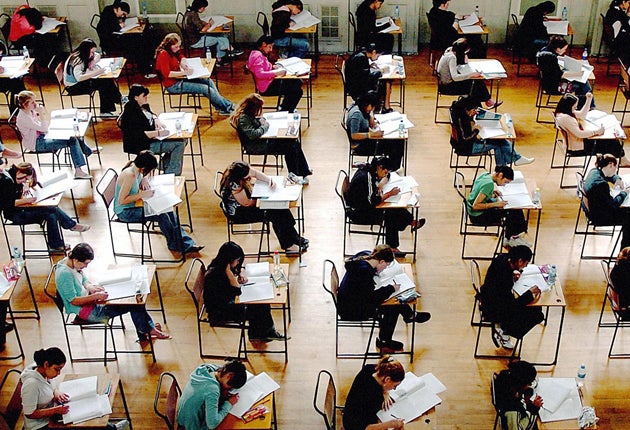

As pupils do some last-minute swotting up ahead of their English GCSE exams, former teacher Susan Elkin examines the changing nature of the syllabus

That opening line still does it. "No one who had ever seen Catherine Morland in her infancy would have supposed her born an heroine." What irony. What elegance. What a hook. One look at it and I'm back in my O-level literature class (never mind how many decades ago), greedily lapping up Northanger Abbey and my first encounter with Jane Austen. My other texts were Henry V and a selection of Tennyson's poetry, both equally life-changing in their way. Many years later, my MA was on 19th-century poetry – by then reprieved from years of critical disdain – and Henry V became my favourite A-level teaching play. I must have done it with at least seven or eight groups, and it never palled.

There is no doubt that O-level/GCSE and A-level set-texts get under your skin and stay there. Sarah Osborne, artistic director at the Yew Tree Theatre in Wakefield, says she fell in lifelong love with Shakespeare through studying The Winters' Tale at A-level and former head teacher Gerald Haigh, now a journalist, tells me that he enjoys still being able to quote large chunks of Romeo and Juliet, his O-level play. Donald George, a retired education administrator, went on to read the rest of Orwell's oeuvre after doing Animal Farm for O-level, and it affected his political thinking for ever.

During the next two or three weeks, around a million teenagers will settle down to answer questions on texts as diverse as To Kill a Mockingbird, King Lear, Carol Ann Duffy's poetry, Keats' odes and Great Expectations. There were 711,196 entries for courses with an English component, and 528,315 for the full English-literature course at GCSE last year. The curriculum usually now requires some set-text work for English as well as for English literature. It adds up to huge numbers of texts being studied by dizzyingly large numbers.

So who decides who studies what? Teachers make choices from lists of options given by one of five examination boards: Edexcel, OCR and AQA in England, the Welsh Joint Education Committee (WJEC) and, in Northern Ireland, the Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (CCEA). There are further different arrangements in Scotland.

"We do market research with more than 500 schools and colleges to find out what texts they would like to teach", says Paul Dodd, qualifications group manager at OCR, who works closely with a team of five or six ex-teachers. AQA, whose spokesperson – rather oddly – asked not to be named, also "engages with teachers", asking which texts they'd like to add to, or drop from, the lists.

The Qualifications and Curriculum Development Agency (QCDA), a Government body which oversees school examinations, specifies that all boards have to include Shakespeare, heritage texts (such as Dickens or Wilfred Owen) and "different cultures" (such as John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart or Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings). There also has to be a balance between prose, poetry and drama. Non-fiction texts are also included.

"One factor we have to consider is cost," say both Dodd and his AQA equivalent. Schools can't afford to keep buying new sets of books. And, if the books are already in use in school, teachers will be familiar with them and have relevant teaching resources – which is why exam boards try not to change the lists too often. But, adds the AQA spokesman: "We have to balance continuity with the need to stimulate teachers and students with something new." .

All GCSE syllabuses are changing this year and schools will begin teaching the new courses in autumn. Some old favourites, such as To Kill a Mockingbird (set by all five boards) are included; others that have been out of fashion for a while, such as JD Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye, are back; while more recent, formerly popular texts such as Mildred E Taylor's Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry – a story written for young readers about 1930s black oppression in the American South – seem to have disappeared altogether. Steinbeck's The Pearl and Gerald Durrell's My Family and Other Animals, once examination mainstays, are nowhere to be seen either, although the latter survives in the more "traditional" International GCSE syllabus (IGCSE) that currently cannot be taught in British state schools (although the Conservatives promised before the election to make it available to any school that wants to use it).

In their place come newer options such as Meera Syal's Anita and Me, a semi-autobiographical account of a 1970s Indian child growing up near Wolverhampton, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Purple Hibiscus, a novel about a black Catholic family in Nigeria. Most unusual of all, perhaps, is Riding the Black Cockatoo by John Danalis – an autobiographical take on Aboriginal repatriation aimed at young readers. It was announced as an Edexcel 2010 GCSE set-text even before it was published in the UK in February.

Another newcomer is Touching the Void, Joe Simpson's account of his ascent of the 21,000ft Siula Grande peak in the Peruvian Andes, which is likely to appeal to boys.

"Teachers report difficulties persuading boys aged 14-16 to read," says Dodd, explaining that he and his colleagues therefore have to look for "boy-friendly" texts such as Athol Fugard's play Tsotsi. "Some teenagers, alas, judge a book by its length, too, and if there are too many pages it will not be popular," he adds.

Every candidate is examined on traditional texts such as Pride and Prejudice or The Mayor of Casterbridge alongside modern fiction and non-fiction texts. "It's a careful balancing act between making literature accessible but at the same time maintaining literary quality and standards," says Dodd.

Austen and Hardy have been set for so long – and so many millions have been introduced to them via public exams – that we don't often stop to wonder how these authors might have felt about the institutionalisation of their work. But modern authors have views, and often express them forcefully. Some, such as Philip Pullman, will not allow extracts of their work to be used for curriculum purposes, presumably because they regard it as reductive.

On the other hand (and this is not a problem for the bestselling Pullman), few things will bring you bigger book sales faster than having your novel or play set for GCSE. Diane Samuels' 1993 play Kindertransport, for example, has been set for A-level English and Theatre Studies for some time. From this autumn, it is also on the AQA English Literature syllabus. Her publisher, Nick Hern of Nick Hern Books, has said how pleased he is, not least because it will drive up sales.

"I am delighted, as I already get emails from students all over the world asking about staging, design and character", says Samuels. "And it's a joy to have more and more students and teachers engaging with the timeless story of child/parent separation."

She has long learnt not to worry about how readers interpret Kindertransport. "Once a work is out in the world, people make of it what they will," she says, adding that, although she gives a lot of talks about the play in schools and elsewhere, "I have for a long while taken the position that I just let people get on with it, hoping that they make some emotional and creative discoveries along the way."

And no, Samuels is not afraid that students are sometimes "turned off" by set-texts. "A set-text is what a student makes of it and often an opportunity to encounter a work of literature or art that you might not encounter otherwise. I doubt if I would have read [Ibsen's] The Wild Duck, [Shaw's] St Joan, [DH Lawrence's] The Rainbow or [Eliot's] The Wasteland if I hadn't studied them for A-level – which meant that I engaged with them on a level of deep acquaintance."

That, for Samuels, makes what she calls "this set-text status" very welcome, because it means that "students really need to give the play some proper attention".

Well, I certainly gave Northanger Abbey some "proper attention" at a very impressionable age – about the same age as Catherine Morland, in fact. I like to think Ms Austen would have approved as I delved into her delicious gothic parody. I hope the million or so teenagers at the examination stage of their educational journey this year will get as much out of their texts. n

The extract

To Kill a Mockingbird, By Harper Lee (Heinemann £18.99)

'...Atticus was speaking so quietly his last words crashed on our ears. I looked up and his face was vehement. "There's nothing more sickening to me than a white man who'll take advantage of a Negro's ignorance. Don't fool yourselves – it's all adding up and one day we're going to pay the bill for it. I hope it's not in your children's time"'

Susan Elkin is the author of study materials to support 'To Kill a Mockingbird' for GCSE. Her work on 'Anita and Me' is published later this year and 'Purple Hibiscus' in 2011 (Phillip Allan Updates, Hodder Education). A 50th anniversary collector's edition of 'To Kill a Mockingbird' is to be published by Heinemann next month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks