Why writers treasure islands: Isolated, remote, defended - they're great places for story-telling

From 'Robinson Crusoe' to 'Swallows and Amazons', what is it about scraps of land surrounded by sea that makes them such compelling settings for storytellers? Author Julia Bell, whose new novel is inspired by 'The Wicker Man', explores some island adventures

In Enid Blyton's The Secret Island the children look longingly at the setting for their adventure.

"The little island seemed to float on the dark lake-waters. Trees grew on it, and a little hill rose in the middle of it. It was a mysterious island, lonely and beautiful. All the children stood and gazed at it, loving it and longing to go to it. It looked so secret – almost magic.

'Well,' said Jack at last. 'What do you think? Shall we run away, and live on the secret island?'

'Yes!' whispered all the children. 'Let's!'"

For a writer, where the story happens is as important to the evolution of the idea as what happens. Setting creates mood and context for the drama, even dictating the kinds of dramas that can happen. We know already that there are many story expectations attached to certain times and places – prisons, police stations, Paris in 1832 – all of these conjure up memories of stories played out in these contexts – a quick mental round up: Orange is the New Black, The Wire, Les Misérables.

So, too, with an island, a familiar place for setting stories since Plato wrote about Atlantis – the island state that dared to threaten Athens, and in return was sunk by Zeus somewhere in the Aegean. But what is it about these places – land surrounded by sea, isolated, remote, defended – that makes for such useful contexts for storytelling? Not to mention the fact that we are, much as we might choose to forget it, an island nation. In the British Isles alone, there are 123 inhabited islands with thousands of smaller uninhabited isles dotted across the whole territory.

Our collective imagination comes to us out of our history and geography and when we look at what we know of our past, especially in the Celtic world, islands were once seen as holy places, wild and monastic, such as Ynys Enlli in Wales, or Lindisfarne in the North-east. Or Skellig Michael, nine miles off the coast of County Kerry, on whose slopes rough cells were built by 6th-century monks, facing directly out on to the Atlantic weather for the purposes of meditation and penance.

In The Wild Places, Robert Macfarlane quotes Bernard Shaw who, after visiting Skellig Michael, said: "I tell you the thing does not belong to any world that you and I have lived and worked in: it is part of our dream world."

And then there are the extraordinary islands of St Kilda, the archipelago of volcanic islands and sea stacks situated 40 miles west of the Outer Hebrides in the North Atlantic. They were inhabited from prehistoric times until the 1930s by an isolated community of "bird people", who evolved prehensile toes suitable for climbing the cliffs to harvest eggs and birds, in a life which seems both impossible and dreamlike.

Shakespeare riffed on this idea of the island dream world in The Tempest – "we are such stuff as dreams are made on" – where the island was the setting for sorcery. Here there are spirits and magic characters – Ariel, Caliban – and magicians – Prospero, Sycorax – who can control the weather and enslave the spirit world. While following the tradition of the romance, the play defies classification as either comedy or tragedy and its use of the elements and the supernatural creates an atmosphere much closer to those of the rugged Celtic islands than the Mediterranean where it is ostensibly set.

Then, in Richard II, comes the famously descriptive, nationalistic speech describing our "sceptred Isle... This fortress built by Nature for her self/Against infection, and the hand of war . . . this little world/This precious stone, set in the silver sea/Which serves it in the office of a wall/Or as a moat defensive to a house."

This sense of moral and physical security led other Renaissance writers to use islands as spaces where they could model political philosophy, Atlantis was revisited by Thomas Moore in Utopia and Francis Bacon in New Atlantis. Both of these works take up Plato's arguments about how society should be organized and promote a utopian, egalitarian vision for how we should live. Moore's book popularised the idea of a utopia – its literal meaning derived from the Greek means "no-place land" – the title becoming even more famous than the somewhat turgid source material. But these works were symptomatic, too, of a nascent sense of empire building. These writers were responding to a new national confidence in the age of exploration. As Britain's seafaring prowess gave her precedence, so these writers felt able to take up the conversation from the Greek philosophers about how a civilised society should function.

The critic Gillian Beer suggests that "the island has seemed the perfect form in English cultural imagining, as the city was to the Greeks. Defensive, secure, compacted, even paradisal – a safe place; a safe place, too, from which to set out on predations and from which to launch the building of an empire".

As the world opened up under the pressure of exploration, so did the literature that was written, and the early 18th century produced two of the most memorable island stories in the British canon – Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe and Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift.

Robinson Crusoe is written in an autobiographical, realist style, and it was Defoe's intention to present it, teasingly, as fact. In his preface he says that he "believes the thing to be a just History of Fact; neither is there any Appearance of Fiction in it". Although the story was based on the life of Alexander Selkirk, who was shipwrecked on a deserted island, the story is a fiction, and one of the most famous and often adapted pieces about survival throughout the almost 300 years since its publication in 1719. There are something like 700 editions, from illustrated children's copies, to translations, to sequels, spin-offs and alternative versions, it's the Ur-text for every survival story you've ever read, including films such as Tom Hanks's Castaway or JJ Abrams's television series Lost.

Like all the best stories, the novel has a simple premise: Crusoe is shipwrecked on a deserted island and has to fend for himself. At first he builds a shelter from what remains of his ship. He then repels invasion by a cannibalistic tribe and then, in one of the most memorable moments in fiction, finds a footprint on the sand that tells him he is not alone. Cue the arrival of Man Friday – named after the day he appeared – who as a sidekick to the main protagonist is as recognisable as any other double acts in fiction: Holmes and Watson, Jeeves and Wooster, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

James Joyce called Crusoe "the true prototype of the British colonist... the manly independence, the unconscious cruelty, the persistence, the slow yet efficient intelligence, the sexual apathy, the calculating taciturnity".

Yet Crusoe is also wise, his solitary sojourn giving him plenty of time to ruminate on the state of humanity. The general life-lesson which still seems pertinent is to appreciate what you've got. Crusoe muses that "all of our discontents for what we want appear to me to spring from want of thankfulness for what we have". The island teaches Crusoe how to be lucky, and in being lucky he represents something of what we hope we might all do in similar circumstances; namely not just survive, but thrive.

In Gulliver's Travels, however, Jonathan Swift uses the idea of an island not for adventure but for satire. It's hard not to see the book, published nine years after Defoe's, as a rebuke to the idea of the individual survivalist. Gulliver is never washed up in places of solitude; instead he encounters societies of various kinds – the most famous, the island of Laputa, literally representing a little Britain, where all the inhabitants are 6in high and the rulers are stupidly intransigent.

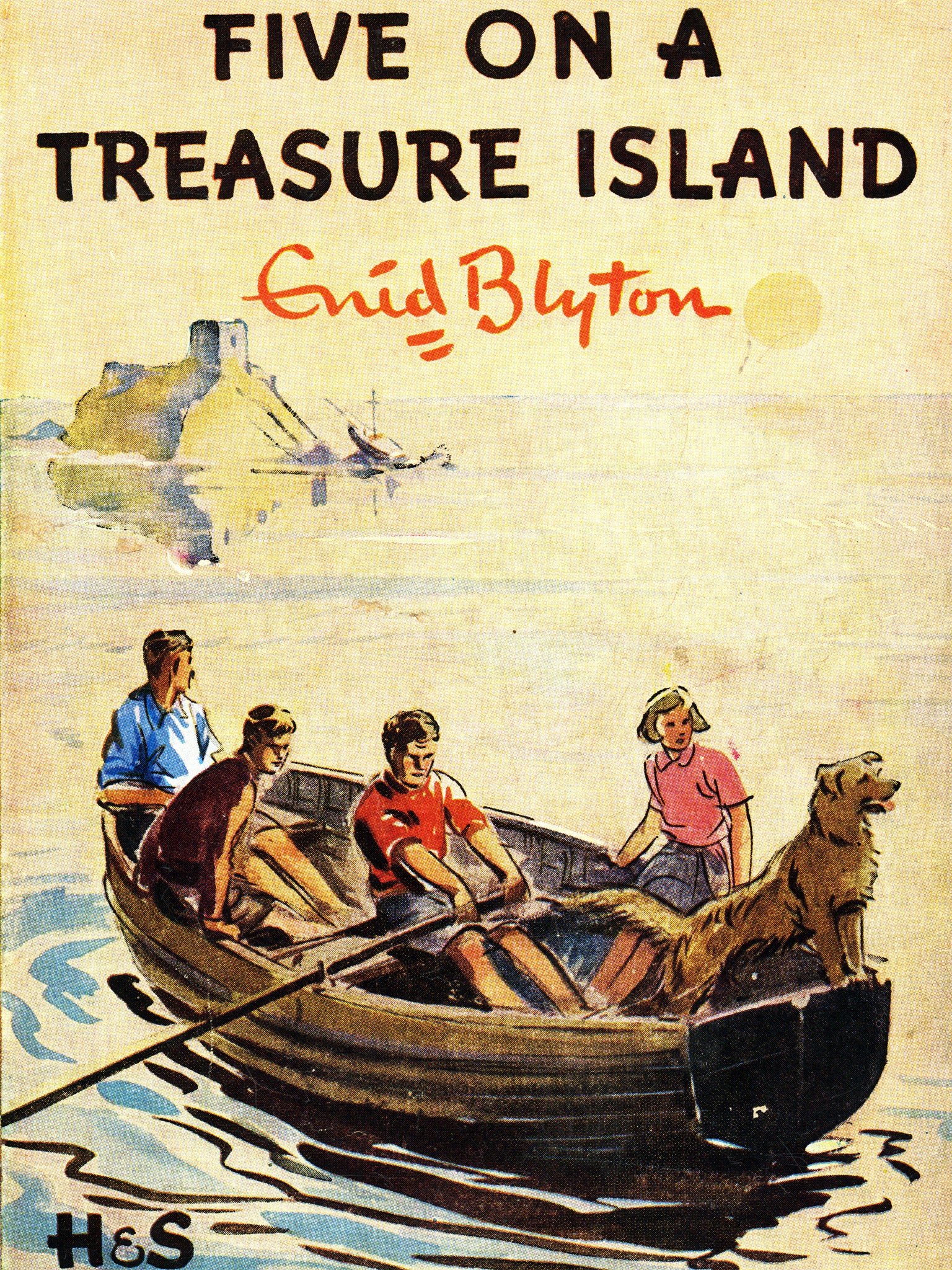

Rather than realist, this story is magic realist: as well as Lilliputians, Gulliver encounters talking horses (which influenced George Orwell's Animal Farm), giants, and the terrible, brutish Yahoos. In one of the most memorable scenes in the book, Gulliver puts out a fire in Laputa by peeing on it, only to find himself in trouble with the king for "making water" and is sentenced to be blinded. He escapes to the neighbouring island Blefuscu (France) and from there makes his way home. Like Robinson Crusoe, the book has never been out of print since its first publication and – stripped of some of its more political passages – has long been a favourite of children's literature. Islands feature across many classics in children's literature, too, Swallows and Amazons, Peter Pan, Treasure Island. For children, islands are personal kingdoms, boundaried worlds which are safe to explore and possess.

But outside the realm of the kingdom of childhood or the launching of empires, the idea of an island starts to turn in on itself once we reach the 20th century. Firstly, in Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse, and then much more seriously in William Golding's Lord of the Flies. An island is no longer a place of safety or adventure, but is somewhere more interior, darker, more dystopian.

In Woolf's novel the island is Skye, where the Ramsays holiday between 1910 and 1920, with a break in the middle in which the characters variously experience the First World War. The main plot, if there is a plot at all, describes a deferred trip to the lighthouse which is finally completed at the end of the book. Woolf's famous stream of consciousness style came from her interest in how she perceived patterns of thought – human beings, she contested, experienced the world not in neat, complete sentences, but in jagged thoughts that changed from one moment to the next.

Her belief was that it was impossible to understand the interior lives of others. In a sense each character is an island of consciousness all of their own – distinct, subjective, never quite connecting: "All the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being oneself, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others."

This interest in the subjective self is very much a theme of 20th-century culture, informed in part by the development of psychoanalysis, but also by the retreat of empire, and in this we can see that islands are no longer the same safe places from which to launch empires, but increasingly intense, mysterious, dark places.

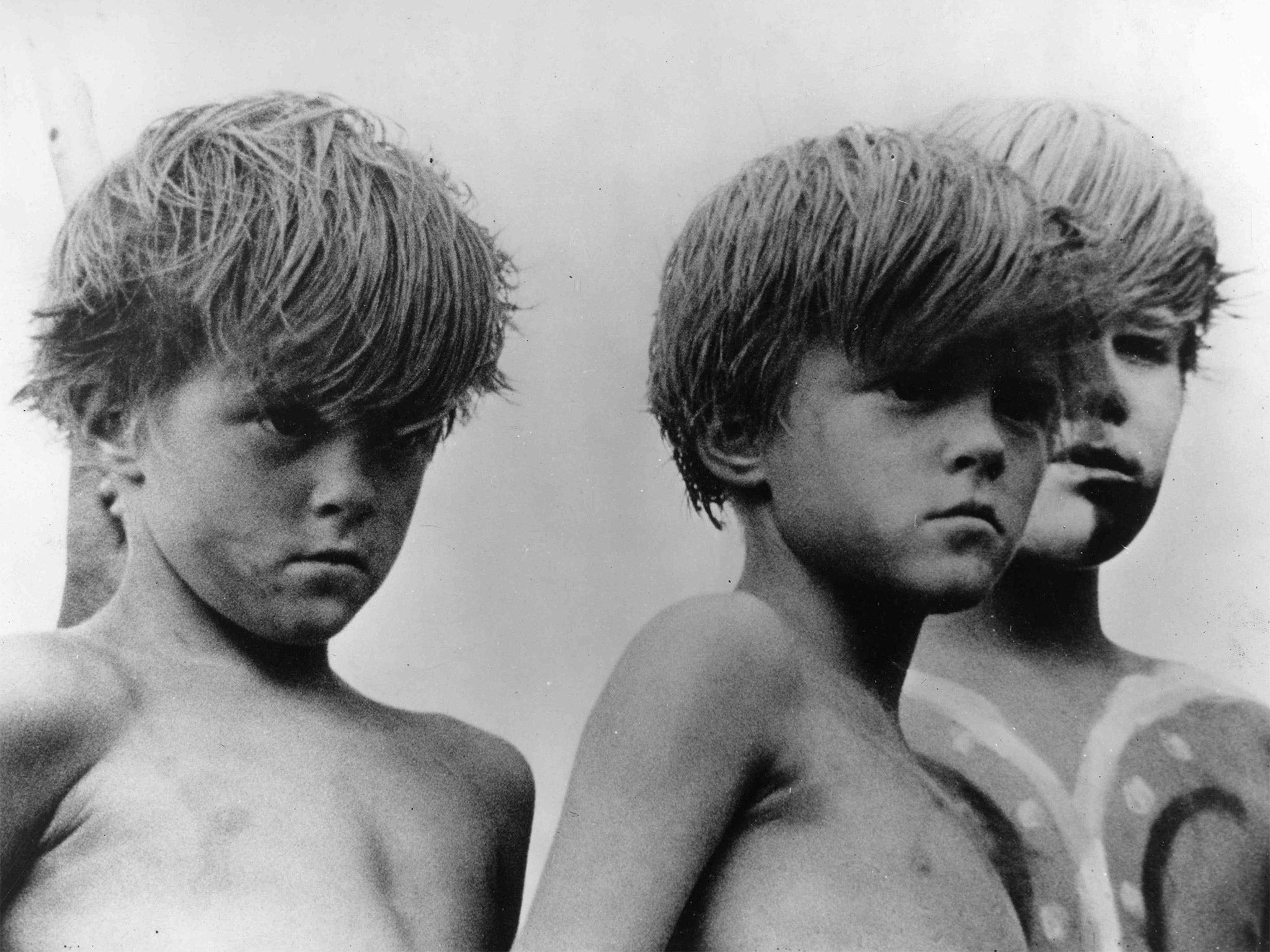

This wedge-shaped core of darkness in the human soul is expanded upon even further in perhaps one of the most famous island stories of the 20th century: Lord of the Flies, which deals with a group of boys, stranded on a tropical island after a plane crash. To begin with, the boys co-operate with each other, but very quickly their nascent society descends into chaos as they begin to bully the weakest member of the group – Piggy – and the story becomes a fearsome allegory of man's inhumanity to man. Golding's point is that, left alone without the containment of civilisation, human beings will descend into savagery. The island space is now claustrophobic rather than expansive, no longer full of brave explorers, or a model society for the purpose of satire or philosophy, but full of savage characters who do terrible things to each other. The island state becomes a prison rather than a castle.

This idea is picked up again in the 1973 film The Wicker Man, where a strange pagan cult is infiltrated by a policeman played by Edward Woodward. The cult leader is played by Christopher Lee, in what he considered to be his finest film. The story harks back to the mystical Celtic "dreamtime" islands, but contains the nightmarish vision of a society that creates rules which are the moral inverse of our own. It was the inspiration for my own novel, The Dark Light, as the island setting meant that the characters could not escape the intensity of the society; they are trapped mentally and physically, which creates a natural claustrophobia to the story.

Benjamin Wood, whose novel The Ecliptic is set in a artists' community on an island off the Turkish coast, welcomes the obstacles which an island setting creates for his characters: "An island setting allows you to set up a pervading sense of dislocation and extremity in the story. To arrive there, and to escape it, your protagonist must face physical and practical obstacles. This not only generates a welcome conflict, activity, and tension in the plot, it also creates a division in characters' identities: the closer they get to the island, the more they are detaching themselves from the ground upon which they have previously established themselves."

In the 21st century, it will be interesting to see what other island narratives emerge. The sense of adventure and security that generated stories such as Robinson Crusoe are far in the past, our new island stories seem much more uneasy, questioning, dislocated. A little bit like our own British Isles.

'The Dark Light' by Julia Bell (Macmillan Children's Books, £6.99) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments