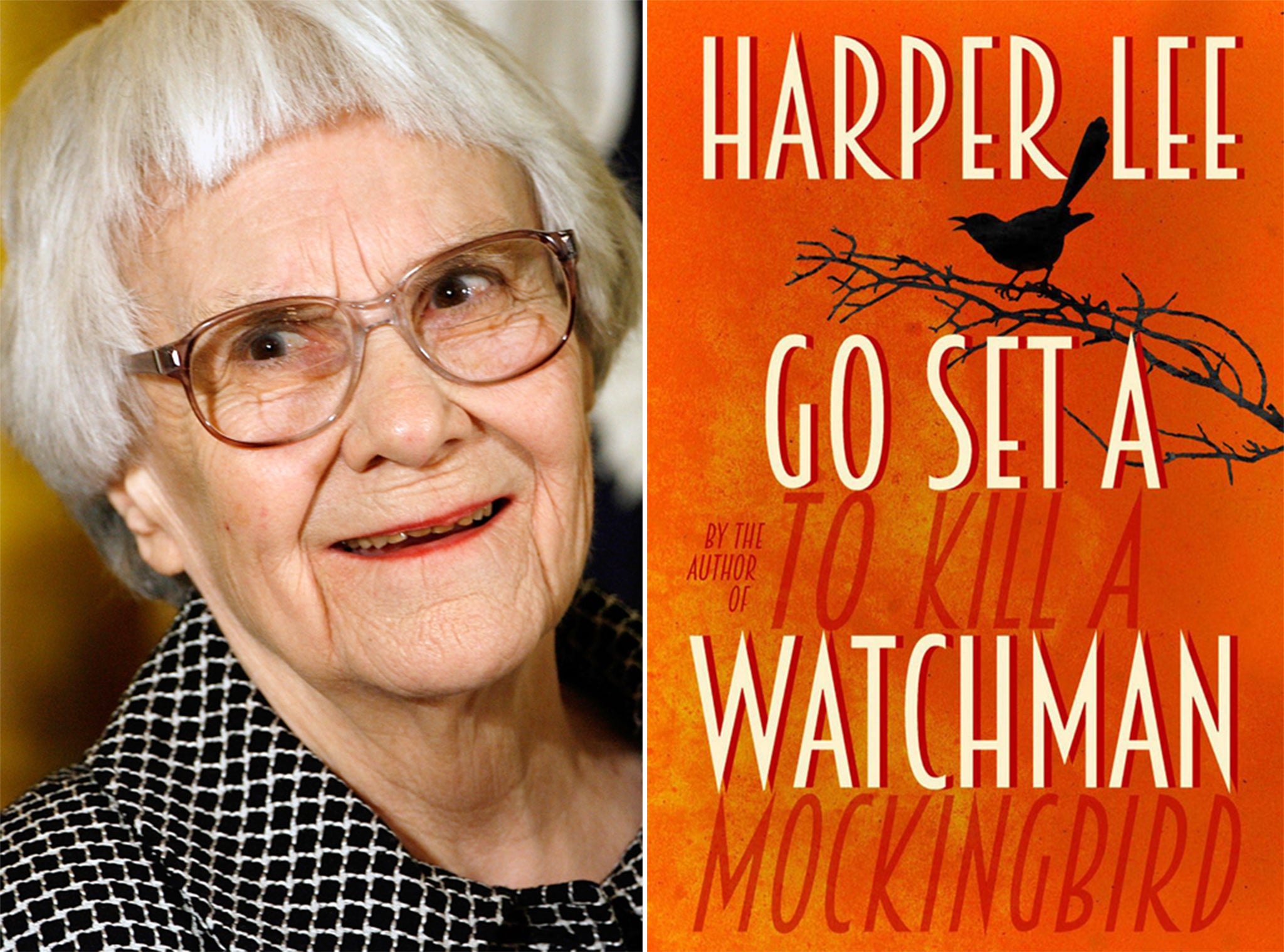

Go Set A Watchman - book review: A rough draft, but more radical and politicised than Harper Lee's To Kill A Mockingbird

We will never be able to read Mockingbird in the same way again, and never see Atticus in the same light. It is the end of innocence for that novel

It is 20 years after Depression-era Maycomb, in the backwaters of Alabama, held its doomed race trial in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Jem is dead of a heart attack; Dill is away in Italy; Atticus Finch has evolved into a small-town bigot who reads pamphlets on “The Black Plague” and regards “our Negro population as backward”.

Scout – Jean Louise Finch, aged 26 – is the new moral compass and Civil Rights activist-in-the-making of Go Set a Watchman.

It is not a finely written story – this reads as a ‘good’ first draft which Lee has refused to rework – yet even in its coarse state where scenes are sketchy, third-person narration shifts haphazardly and leaden lectures on the Southern States’ racial history stand-in for convincing dialogue - it is the more radical, ambitious and politicised of the two novels Lee has now published.

It deals with the scourge of racism in civil rights era America (found in the hearts of otherwise ‘morally upstanding’ individuals like Atticus) whose trajectory can be traced to America’s relationship with its black community today, and to the Charleston shootings. In this sense, it has contemporary relevance where Mockingbird is safely sealed off as a piece of American history, with all the hope its ending brings for Maycomb’s growing racial tolerance.

It does not undermine Mockingbird but it makes a reassessment of that story absolutely necessary. Set-text students may now look for signs in that book for Atticus - the racist apologist (when he forces young Jem to read aloud to the openly racist Mrs Dubose? When he asks Scout to step into the shoes of the lynch mob who want to attack the black defendant, Tom Robinson, in jail?).

In the end, this is the most shocking aspect of Lee’s novel, published 55 years after she was advised to discard it and focus on the children’s story instead - that we will never be able to read Mockingbird in the same way again, and never see Atticus in the same light again. It is the end of innocence for that novel, and its simple idealism.

That novel made a civil rights hero out of Atticus, for his courageous courtroom battle to save Tom Robinson, wrongly accused of raping a white girl. He urged Jem and Scout to stand up to an entire community baying for blood. Yet here he is in Go Set a Watchman, in his early 70s, entrenched in reactionary racism. Just as Scout watched him attempting to save Tom 20 years ago from the “colored gallery” of the courtroom, she now stands in the same spot, watching him attend a meeting on the dangers of desegregation, admitting to have been to a Ku Klux Klan meeting years ago, and speaking of the black community (and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) in offensive, threatened and paternalistic terms.

If he personified the intrinsic Christian goodness of the Southern white male in Mockingbird, that Southern male has turned mean, racist and small-minded, now that the Civil Rights struggle, and prospect of equality for all, is so much closer than it had been in the mid-1930s of Mockingbird.

Many have spoken cynically of the marketing value of Go Set a Watchman, but one wonders whether Lee’s original editor was thinking about just that when she asked her to discard this angry, incriminating story, which incorporated the race issues of its day (such as the debate on desegregating schools going through the Supreme Court), and write something more ‘nostalgic’, perhaps in order to sanitise it, and make Atticus more palatable to White America.

Despite the boldness and bravery of its politics, Go Set a Watchman is a very rough diamond in literary terms: comprised heavily of flashbacks into childhood in which Jem and Dill are still Scout’s playmates, and memories of teen romance, and angst, that lack the emotional detail and impact of Mockingbird; there is a moving scene when Scout visits the former, black housekeeper, Calpurnia, (who is a surrogate mother of sorts in Mockingbird) in which Cal refuses to look Scout in the eye, and sees her merely as the oppressor – “She sat there in front of me and she didn’t see me, she saw white folks”. Redrafted, the scene would surely have been emotionally devastating in Lee’s hands, and that goes for so many of the flashback moments that could have held a far greater emotional charge, had they been worked upon.

In this respect, it is a book of enormous literary interest, and questionable literary merit. It cannot match Mockingbird for its bewitching prose, its brilliance in capturing the Southern demotic, its exquisite picture of childhood play and innocence, corrupted by an adult world of race hate and injustice. There are various plot glitches: Scout’s romance with her childhood friend, Henry, brings with it the central question of the novel - whether she will marry him. But that romance is all-but-forgotten in the final chapter, and we are left wondering. And in spite of the many flashbacks, not one describes Jem’s death in any detail, nor Scout’s emotional response to it.

The storyline is limited too, hinging on one incident – Scout’s shocking discovery that her father is not the unimpeachable moral force that she thought he was. Yet it works, somehow. If Mockingbird is a story about childhood before it is one about racism, this is a coming-of-age novel in which Scout becomes her own woman. “The one human being she had ever fully and wholeheartedly trusted had failed her; the only man she had ever known to whom she could point and say with expert knowledge, ‘He is a gentleman, in his heart he is a gentleman,’ had betrayed her, publicly, grossly and shamelessly.” Her betrayal and hurt over Atticus’s change is also ours. “You’re a coward as well as a snob and a tyrant, Atticus,” she tells him, when he continues to argue his case in the final third of the novel, which brings its own kind of courtroom scene, of daughter interrogating father.

Even with its weaknesses, Go Set a Watchman’s voice is, at its best, beguiling and distinctive, and reminiscent of Mockingbird, and its similarity in style might finally end the speculation that Lee’s childhood friend, Truman Capote, “helped” to write Mockingbird (unless we are to believe he wrote this one too, but then there would be the puzzle as to why he wrote himself – Dill was apparently based on the young Capote – out of this book).

Whatever its failings, Go Set a Watchman can’t be dismissed as literary scraps from Lee’s’ imagination. It has too much integrity for that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments