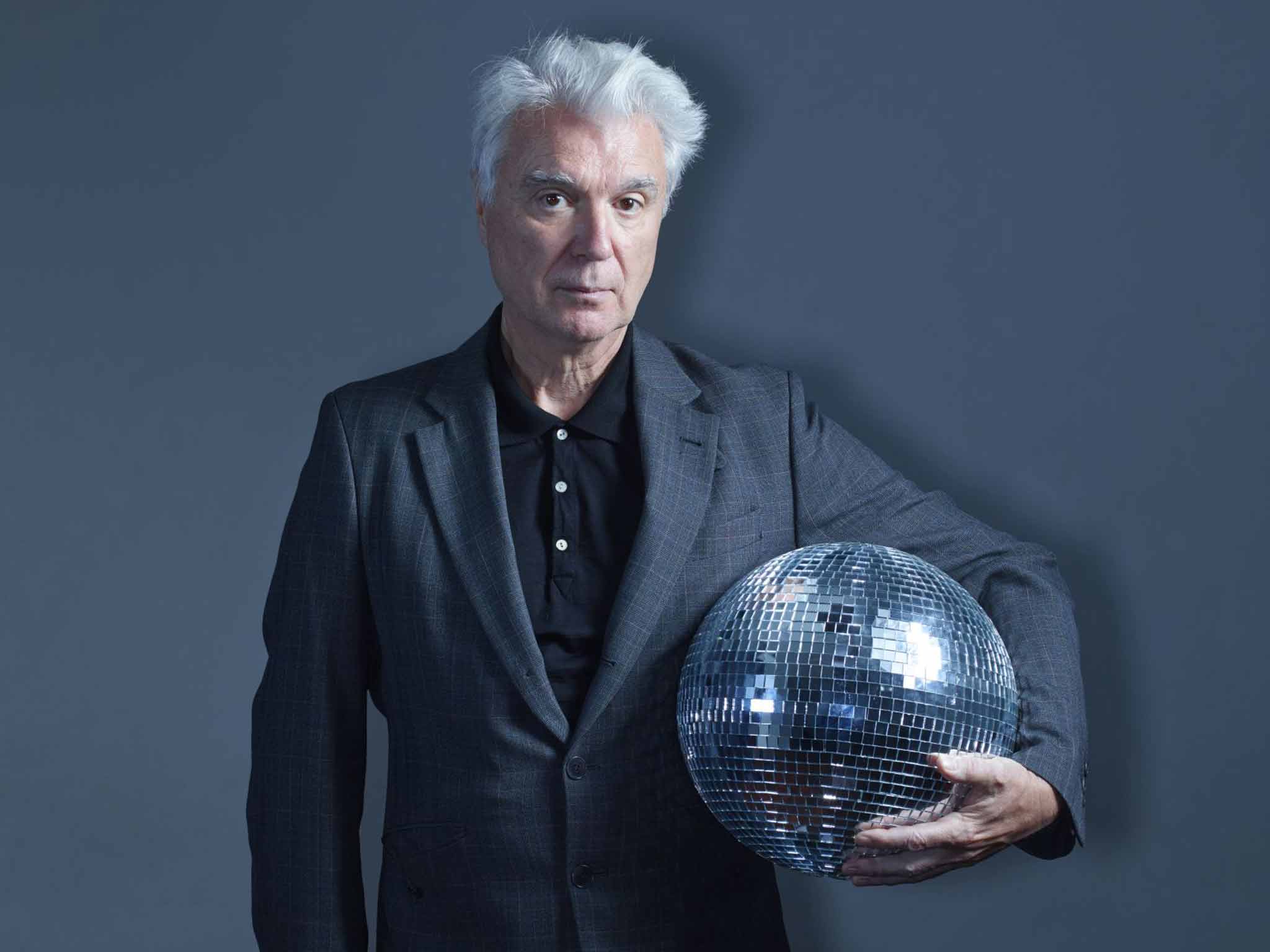

David Byrne on his Imelda Marcos musical

How do you write a disco musical about Imelda Marcos? By putting yourself in her fabulous shoes, of course. David Byrne describes how the notorious First Lady's high life dazzled him out of a career low

There was no sudden flash of inspiration that told me I needed to do a disco musical about Imelda Marcos. The idea didn't arrive fully formed, but came into focus gradually. Here's how this improbable thing started.

Maybe a decade ago, I had an insight while reading Ryszard Kapuscinski's book The Emperor, about the court of Haile Selassie, the former ruler of Ethiopia. It seemed to me that the bubble world of a powerful person as depicted in that book, and possibly that of many powerful people, is not unlike the artificial world of much Asian theatre. The behaviour is prescribed, ritualistic and regimented. A kind of dance of power. And, given the similarities between Asian theatrical forms and the world of downtown New York theatre, a world I had a sometime relationship with, I thought, maybe someday… and then filed that insight away. (I later heard Jonathan Miller did a stage and TV adaptation of The Emperor, so I wasn't the only one who found a kind of theatre in that book.)

Some years later, I read in a newspaper that, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Madame Marcos had a mirrorball installed in one floor of her New York townhouse, and that she loved going to dance clubs. I am old enough to have recalled her going to nightspots while her husband, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, had the Philippines under martial law. I found it disturbing that Andy Warhol, for example, an artist I admired, would hang out with Imelda at fashionable discos. I had followed the political bombings in the Philippines, the assassination of Benigno Aquino in 1983, and the People Power revolution that ousted the Marcoses a few years later. Those events were worldwide news. And of course, everyone knew about the shoes that were discovered after the revolution. Given my political leanings, I didn't particularly like this person.

I remembered my previous insight, and wondered whether this powerful woman had a story arc beyond those famous shoes. And, if so, wouldn't it be cool if that pulsing sonic world she inhabited helped tell that story?

David Byrne and Imelda Marcos

Show all 4How would that happen? Well, years ago I'd sometimes see what were called "track acts" at some of the big warehouse dance clubs in New York . In those shows, the singer would arrive (Gloria Gaynor, say, or maybe Freda Payne, who had a big club hit or two) sing a couple of hits over a backing track to an adoring crowd, and in 20 minutes they would be gone. The performance would be on a small, makeshift stage, not much more than a platform really. It was often little more than a diversion – and that was it for "live" music in dance clubs.

When I conceived this piece, there were still some of those mega-dance clubs in most big cities, so, I thought to myself: what if those 20 minutes became an hour-and-a-half, and there were multiple singers whose songs – all in the club genre – actually told a story? The story of someone who hung out in those clubs and surrounded herself with that music. Maybe some video projections would help with the exposition, but mainly I imagined a kind of mixtape – albeit one that had narrative and emotional depth – with live singers. Your evening out wouldn't just be informed by the arc of the drugs you took or the DJ's picks, but by a real story. It seemed to me that the story of Madame Marcos would be perfect in that setting, right? She brought the extra element of Imeldific fabulousness as well – which is also perfect for those venues where I first imagined this piece being performed.

Would another powerful person have worked as well? The Bush White House maybe? (Condi Rice-led singalongs, post-9/11.) Or maybe some billionaire who lives in a bubble world? But those folks didn't come with a built-in soundtrack – and in a genre I feel comfortable with, at that. I also suspect that the headiness of dance music, the way that you are transported and can lose yourself, may mirror some of the feelings inside those bubbles of power. The musical connection might not be entirely accidental.

I know, I'm not actually answering the question "Why?". I remember the director Robert Wilson once saying in an interview that he couldn't explain why he made things the way he did, but that he could tell you how. Well, I can guess at some pragmatic reasons why I would dive into this: I'm not getting any younger, and though I love performing, I imagine I might have secretly harboured a desire to find a way to make a performance without me in it. Second, although this was conceived at least 10 years ago, when music fans still purchased whole albums, the temptation to make something in which every song is integral to the piece might have lurked. And last, although the sales of recorded music had yet to fully collapse, I may have sensed that it might not be a bad idea to find other creative avenues, which might provide revenue beyond the sales of records. (I didn't actually sit down and consciously think, "Decline in records sales – disco musical!" but those reasons might have been hovering in the background.)

Those reasons why are all very pragmatic, but mostly the urge was creative. I noticed that the Talking Heads concert that was filmed for Stop Making Sense in 1983 had a narrative arc, in a sense – and that psychological storyline made it more deeply satisfying and resonant than if it was just a bunch of songs strung together. So I knew that pop music could do that; it wasn't impossible. And also that you don't need all the dialogue scenes typical of most Broadway musicals to have emotional and narrative impact. So why not take all of those ideas further?

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

I set to work reading about Imelda's life and times, to see whether there was a story beyond the shoes and the rise and fall of a glamorous and very public dictator's wife. I knew right away that, despite my misgivings about Madame Marcos, I had to find a way to understand what made her tick. And to do that, one had to empathise with her – at least for a while.

The first story I latched on to was that of the relationship between Imelda and Estrella, her former maid and best friend, as detailed in a biography by Carmen Pedrosa. Estrella, I imagined, could function as a foil; illuminating Imelda's denial of her own relatively poor childhood, as well as serving as a victim when Imelda turned to the dark side after martial law was declared in the Philippines.

As I read more, I saw recurring mentions of the fact that Imelda used to date Benigno Aquino, her future husband's chief political opponent, who would be assassinated when he attempted to return from exile to Manila in order to challenge the Marcos regime. Aquino broke up with her when they were both young, claiming she was too tall. (She is very tall for a Filipina.) Yet this bit of romantic information was often only mentioned in passing, so I didn't want to give it too much weight and, besides, it seemed too good a narrative device to be true. To imply that later sweeping political events were the result of romantic rejection seemed too simple.

Having the outline blocked out as scenes, each of which would be told as a song, I approached Norman Cook, out of the blue. I'm a Fatboy Slim fan and I thought Norman would be perfect to collaborate with on this, as he would make it sound like proper club music. Plus, he doesn't work in only one genre (house or techno or garage) as so many electronic musicians tend to do. And finally, he'd been in a band once (the Housemartins), so he knows what a song is – verses and choruses – as opposed to knowing only 10-minute long trance grooves. Norm agreed to give it a try, so we soon exchanged tracks. He sent me some beats to write over and I sent him some song sketches that needed better grooves and fleshing out.

The writing on my end moved relatively quickly. The words came first – I'd already culled lots of quotes from all the relevant characters and assigned them to pivotal points along k the story. I therefore didn't have to imagine what the characters would say – they said it themselves, on record. Pure gifts for a lyric writer. Aquino, for example, once referred to Imelda as "the fabulous one" in a speech he gave to the Philippine senate, so that got used in a song. Madame Marcos was once quoted as claiming that she was the people's "star and slave" and that her country, like herself, needed to put on a "pretty face" for the rest of the world to see. I couldn't have expressed the complicated psychology at work any better.

I decided that before I went any further I should visit the Philippines, and ask the locals if I was completely off base. I met with local creative types – writers, film-makers, photographers and such – but also with Marcos loyalists, and a woman who represents Madame Marcos in some capacity. (Yes, she's still alive – she returned from exile some years ago, and she's back in government. I didn't get to meet her.)

I travelled to the north – Ferdinand Marcos's homeland – and to Tacloban, in the south, from where Imelda's family hails. I read that, after the typhoon that devastated that town in November last year, Imelda's friends in Manila opted to shield her from the worst of the news.

My song demos were deemed not wrong by my friends in Manila. Phew! But what I discovered, which was more important than any specific information, is that nothing in the Philippines is black and white. We in the West like our stories and politics simple, with clear-cut good and bad guys. I knew that most Westerners would bring a lot of baggage to a show about Imelda – as I did at first. They'd remember the years of partying and repression and the embezzling of massive amounts of money. The Filipinos remember that too, but they also remember the good things the Marcoses did before things took a turn. Ferdinand and Imelda did build the roads, hospitals, schools and art centres that they promised – and that many remain proud of. Some of my friends went to film schools she started, and are thankful for their existence. So, I realised, it's complicated.

This more nuanced view actually suited my storytelling – at least in the first half of the piece. Getting a Western audience to feel for Imelda in the beginning was not going to be easy, given the aforementioned baggage. But with all the sentimental and pithy quotes she and others gave, I thought it might be possible. I knew I'd run the risk of folks saying I was apologising for her, but I thought that by the end of the story, which would be the People Power Revolution that ousted the Marcoses, that initial empathy would come to make sense. It would mirror the sense of betrayal the Filipino people felt.

Now, having seen this piece in front of audiences, and with a lot of Filipino actors in the cast, I have come to realise that often they themselves, and certainly a younger theatre audience, don't remember these events. Would they care? Would it seem like ancient history? I didn't want to be giving a history lecture here! But it turned out they do care.

The show has dredged up what was almost forgotten, even in the Philippines. Many of the cast members' parents were there during the Marcos era. In some cases, those days weren't discussed at the dinner table. But the show, I'm told, made those memories resurface, and families began to talk. It's flattering and thrilling.

Ultimately, the show is about Imelda. (By the way, she has apparently listened to the show's soundtrack. I have no idea what she thinks of it.) But it is also about this incredible thing the Filipino people did to peacefully oust a dictator – and how things got to that point. I cry almost every time I see it – and I know what's coming! (I sing along and dance too.) So this reaction answers the original question, "Why?". When these things work, they can, if one is really lucky, have a wider and deeper effect than a batch of songs strung together. That effect, revealed in retrospect, makes the years of work on something worthwhile, and sort of explains why one would ever do something as odd as a disco musical about Imelda Marcos. 1

'Here Lies Love' is at the National Theatre, London SE1, from Tuesday to 8 January

Imelda: A life

* Born Imelda Romuáldez in Manila on 2 July 1929, she was the oldest of six siblings, growing up in relative poverty in the eastern Philippines province of Leyte.

* Moving back to Manila as a young adult, Imelda found work singing at a record store, and later as a model, coming second in the Miss Manila beauty pageant.

* In 1954, she met up-and-coming congressman, Ferdinand Marcos. The two married 11 days later.

* Ferdinand Marcos became president in 1965, Imelda becoming First Lady. To hang on to power, President Marcos declared martial law, in 1972.

* Imelda became notorious for her lavish lifestyle as First Lady, including dispatching a plane to pick up tonnes of Australian white sand for her own beach resort.

* The backlash against their rule, known as the People Power Revolution, led to Imelda and her family fleeing the country into exile in Hawaii, in 1986.

* Imelda left behind: 15 mink coats, 508 gowns, 1,000 handbags, and 1,060 pairs of shoes – 765 of which are on display at the Footwear Museum of Marikana.

* Following the death of her husband in exile, in 1989, Imelda was given amnesty by then-president Corazon Aquino and returned home.

* More than 900 suits were filed against the Marcoses, to recover allegedly misappropriated state funds; to date, no one has been successfully prosecuted.

* Aged 85, Imelda still lives in Manila, serving a second term as a congresswoman for her late husband's province, Ilocos Norte. Adam Jacques

* Marcos once said: 'I was born ostentatious. They'll list my name in the dictionary someday. They'll use Imeldific to mean ostentatious extravagance.'

1

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies