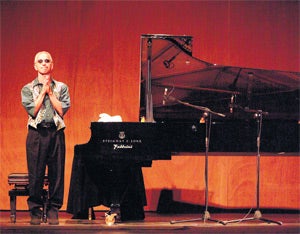

Keith Jarrett - The fine art of extra-sensory improvisation

The jazz giant Keith Jarrett talks to Kevin le Gendre about the challenges of playing what has not been played before, the struggle to avoid self-repetition and the need for a life away from the city

A cruise ship crossed the Caribbean Sea some time in the mid Eighties. On board were the feted English Chamber Orchestra, the celebrated opera singer Kathleen Battle and the virtuoso pianist Keith Jarrett, one of the few genuine marquee names that the jazz world has. One can only imagine what this vast array of talent produced for Floridian pensioners in need of some pep after a leisurely afternoon by the swimming pool, or perhaps too lengthy or costly a stay at the blackjack table in the casino room.

One can only imagine the glee of the serious music lovers when Jarrett took an unscheduled decision. "I decided to give a little talk about jazz and classical music," he recalls on a clear line from his home in New Jersey. "The night before, Kathleen sang spirituals like 'This Little Light of Mine' and I thought the words described the differences between jazz and classical. 'This Little Light of Mine' is about knowing you already have 'it' versus 'I gotta go get it.' I think the going and getting is more like a classical thing and the already knowing you have your own thing is a jazz thing.

"Classical is when you're just trying to control it all. It's that control which is exactly what jazz is not necessarily asking me to do, but just speak from myself." Jarrett is as qualified as anybody to make such an observation, having played the works of Mozart and Bach on several occasions throughout a 40-year career that has seen him ascend to the kind of superstar status rivalled only by the likes of Herbie Hancock, another virtuoso jazz pianist who has also plunged into classical waters many a time.

Although he made several accomplished quartet albums in the Seventies and Eighties, Jarrett, who emerged as a sideman with Charles Lloyd in the late Sixties, has made the biggest splash in two formats: the Standards trio, dedicated to breathing life into the classic Broadway songbook, and as a solo pianist. Testament Paris/London, his new three-CD set, is drawn from two unaccompanied concerts he performed in those cities last winter. Looming large in the sleeve notes that Jarrett has penned, an unusual move for an artist who generally keeps his counsel, is the endeavour to avoid repeating his former glories, a pivotal concern for a jazz musician. The dense harmonic architecture of the 1975 solo set, The Köln Concert, the monster seller that made Jarrett a star, had to be partially torn down in order to find an approach that was fresh, if not more distilled.

As he did on the 2005 set Radiance, Jarrett is finding more natural pauses and breaks in his stream of ideas. "Whenever I would play something that was from the past and sounded mechanical I would stop," he writes. "This led me to include stopping and starting in solo concerts in Japan." Jarrett "shorts" can be rewarding.

For all his knowledge of chords, and how to take them apart and find sumptuous voicings, Jarrett is often at his most inventive, if not appealing, when creating the most simple theme while unveiling astute, delicate nuances in his touch on the keys.

He does wordless songs, so to speak. Jarrett's lyricism is arguably his greatest gift. But that ability to sing through the keyboard is outweighed by a much larger concern, and it is something that goes right to the very heart of the jazz aesthetic: spontaneous invention. A great irony of the improviser's lot is that there is an enormous technical requirement to meet, something the 64-year-old has pursued since graduating from the renowned Berklee Music School as a teenager, yet there is also a need to transcend if not negate it in order to find something truly novel. You learn, then learn to unlearn.

"People think that if you do this 500 times somehow you know it," Jarrett contends. "Well, the more you do these things, the harder it is to really do them as new. I never go with what I feel an audience wants and also I'm not even going with what I want. I'm just trying to let my feelings tell me... show me a sound I haven't heard."

Revealingly, Jarrett recalls a personal incident that occurred in a very distant past. "I remember my youngest brother, Chris, when he was a kid, he had a difficult childhood and he didn't know anything about pianos but there was a little upright in my mother's house. Chris would go to the piano knowing nothing about it, and maybe he was in some emotional trough or something, and I remember telling myself there were moments when he was playing that were just so, if I could use the word, 'cool'.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

"But he did not know what he was doing. And I thought well, OK, how can someone get to that if they actually do know the piano in the first place? That must be impossible. And I remember really thinking that when I was still a teenager, so just now I'm trying to learn ways of doing it.

"Before I didn't tell my left hand... 'just do something'," he continues after the briefest of silence. His voice is relatively soft but nonetheless very assertive. "I didn't let it breathe. I'd been keeping it in chains all this time, playing vamps. Well, that's cool but I wasn't really using both hands in an equal fashion, let's put it that way."

In concert, this liberation requires absolute focus and a kind of single-minded commitment to the creative act, at least one that is devoid of clichés or any kind of pre-prepared licks. Jarrett thus attempts to empty his mind as fully as possible before he reaches the stage.

When pressed on exactly how this can be achieved, the pianist opts for the image of the blank canvas, and then quickly elaborates by saying that, "The sensors are on but the cerebral, qualitative thinking is not happening."

Several groups in the history of jazz have scaled great artistic heights by way of advanced, almost intuitive interplay between individual members – Jarrett's Standards trio's London gig this summer was a case in point – but the solo performance is more demanding because there is no other mind off which the single player can bounce, no accomplice and sparring partner who offers both support and challenge.

Hence Jarrett, who withdrew from performing for two years in the mid Nineties due to chronic fatigue syndrome, has to converse, in very quick time, with his own impulses or emotions and decide how to draw a narrative arc from passing melodies, or fragments thereof. He also has to judge what may be easy or not so easy on the ear; and, interestingly, he is edging more towards atonal pieces.

"Beauty is so narrowly defined by most people," he argues. "Take a language and blurt it out to someone who's never heard that language. In the beginning they'll be taken aback and have no idea what you're saying, but if you keep speaking you can, I think, bring them around.

"Almost all sounds can have beauty but it's a case of opening up, clearing the mind to hear that they do," he says. "Too many things happen inorganically when you're improvising because you're thinking too much. You're thinking about what to select and what not to, so I kind of force myself to remember that while I'm playing and one of the ways I do that is by letting my hands do something before my brain can deal with it at all.

"When a motif appears – even if it's almost nothing – there's a moment when I say to myself, am I going all the way with this? And if so, do I risk being boring or difficult? Or, in the critics' words, I would just be somebody who is self-indulgent."

They have, in fact, called him much worse over the years, and Jarrett's instances of prima-donna behaviour, right down to withering outbursts at the slightest cough or whisper from an audience, have earned him a nuclear reputation. Some of his chastising may have combusted into excess but his demand for cathedral-like silence raises a legitimate point about jazz soloists still having to seek the reverence granted classical orchestras.

A more interesting question, perhaps, is what happens when the pianist is away from the concert hall. His daily existence in a house, as he puts it, "out in the woods", built into a hill and overlooking a lake in Oxford, New Jersey, is one in which proximity to nature and a distance from the urban squall are crucial. Solitary is salutary for him. Even in the wake of the recent breakdown of his second marriage.

"When my wife left, she expected me to move to New York... and I didn't," says the pianist. "I looked out the window and it was a very simple decision. I need a lot of isolation to create. If you don't have a space to come from, exactly what are you delivering to a hall? So I live in the country but I don't play country music... at least not what they call country.

"I realised anytime I came home, the thing I was missing was the sights and sounds from this property. It's very lush, real winters, real summers. Everything changes all the time, you see struggle and that struggle to me is a parallel to the artistic struggle."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks