Sign up to Roisin O’Connor’s free weekly newsletter Now Hear This for the inside track on all things music Get our Now Hear This email for free

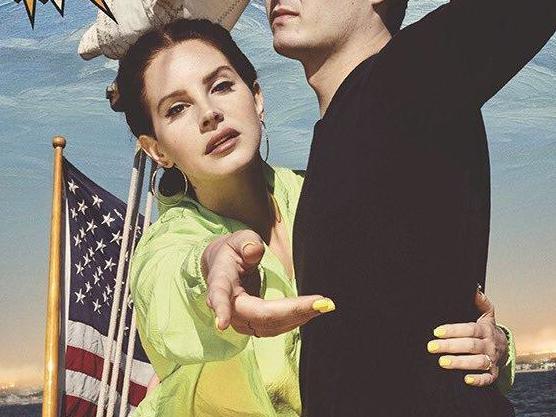

O n a long drive through the dark last week, I listened to the new songs from Lana Del Rey ’s sixth album on a long, repeating loop. Norman F***ing Rockwell! contains a little more guitar grit than previous records, but the swooning nostalgia of the sound is unmistakably Del Re y.

Earlier in the trip, I’d steered the radio away from news of burning forests and Brexit. The cool blues of the music were pure relief. The repetitive rise, curl and fall of the melodies, the sad/sweet solace of her voice washed over me like waves. I felt my breathing slow with hers as she continued to dive into her “darkness, deepness/ All the things that make me who I am”. I’ve not heard it all yet, and already the beautiful, difficult, literate Norman F***ing Rockwell! feels like the record to get me through 2019.

But I still feel a little uneasy publicly declaring my love for Del Rey. Probably this is because the ground has been shifting so fast beneath the feet of musical heroes – from Michael Jackson to Morrissey – that my emotional attachment to music is still in a weird state of flux. And Del Rey is a divisive figure.

Styled as a pouting pin-up from a mythical American underworld, she wrote her first four albums from the perspective of women who dream of nothing more than popping beers for bad guys playing video games. She romanticised domestic “ultraviolence”, had herself choked in videos and recycled The Crystals’ 1962 line, “He hit me and it felt like a kiss”.

I notice my male friends are far more willing to celebrate her embrace of this masochism than my female friends. One (female) friend who works with victims of domestic violence loathes her. She says it’s the privilege that I share with Del Rey (who was born into a white, well-off, well-educated family) that allows me to enjoy this stuff. For a long time, Del Rey claimed not to be interested in feminism , which didn’t help my cause in the arguments where I found myself defending her.

I’ve also got a couple of friends (again, women) who feel Del Rey lacks the authenticity they crave in music. They point to the various pop personae she tried on – including Sparkle Rope Jump Queen – before creating one she could sell. They make it a point of pride to quote the Pitchfork review in which critic Lindsay Zoladz dismissed her 2012 breakthrough album, Born to Die , as: “a faked orgasm”.

Well, the accusations of fabrication are easy to dismiss. There isn’t a pop star out there who hasn’t created a persona. I don’t care that Lana Del Rey isn’t her real name and I don’t care that she probably learnt a trick or two about selling fantasy from having parents in the advertising industry. Del Rey didn’t care either. “Luckily, I always thought, F**K YOU!” she says in a recent interview. And she dealt with accusations that an industry boyfriend helped her up the ladder with the conversation-killing bluntness on the song “F***ed My Way Up to the Top”.

The stuff about her “antifeminism”? That’s more complicated and – as someone who argued for too long that Morrissey’s “National Front Disco” was obviously taking the piss – something I’m worried about reading wrong.

But I do see feminism in the narrative of Lana Del Rey. Born Elizabeth Woodward Grant, in New York, 1985, she once said the monologue on 2012’s “Ride” is “semi-autobiographical” – which makes it worth quoting.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up “I was always an unusual girl,” runs the song. “My mother told me I had a chameleon soul. No moral compass pointing due north, no fixed personality. Just an inner indecisiveness that was as wide and as wavering as the ocean.” Her childhood included singing in church and being packed off to boarding school, aged 14, to recover from alcohol addiction.

At 18, she picked up the guitar and began playing in nightclubs as Lizzy Grant and the Phenomena, and other characters. She was signed by an independent label in 2007 but her debut album was shelved, and she threw herself into working with the homeless and on drug and alcohol outreach projects. She’s not just a rich kid imagining the self-destructive characters in her songs: she spent five years listening to them before bringing their voices out of the shadows. On the new album she still sighs that: “Spilling my guts with the Bowery bums/ Is the only love I’ve ever known/ Except for the stage, which I also call home.”

As Grant found her way towards the sound she wanted, her dad helped her buy back the rights to her shelved record. While the naysayers claim the Lana Del Rey persona was created by record label execs (because how could a woman possibly rebrand herself?) she has always been clear that the character’s her own creation. The Del Rey part is after a vintage Ford and the Lana is in tribute to glamorous – but deeply troubled – film noir star, Lana Turner.

Show all 67 1 /67The best albums of 2019 (so far) The best albums of 2019 (so far) Rina Mushonga – In a Galaxy It’s not uncommon for an artist to be influenced by the place they grew up in. Yet few are likely to have as much inspiration to draw on as India-born, Zimbabwe-raised and now Peckham-based artist Rina Mushonga. The singer-songwriter’s nomadic personality is reflected in the vast scale of reference points on her new record, In a Galaxy. It’s technically a follow-up to 2014’s The Wild, the Wilderness, but the newfound boldness on this new work is startling. Since that first record, Mushonga has begun to incorporate themes of empowerment into her work. On “AtalantA”, she showcases her muscular vocals, which are capable of switching between an airy lilt to a deep, emotional moan, as she sings lyrics inspired by the Greek hunter goddess who refused to marry. In a Galaxy is a record that takes you far beyond the borders of the world you’re familiar with, and into something altogether more colourful. (Roisin O'Connor)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Deerhunter – Why Hasn't Everything Already Disappeared? On Deerhunter’s eighth album, frontman Bradford Cox takes on the role of war poet, documenting the things he observes with a cool matter-of-factness, and heart-wrenching detail. Death is everywhere on Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?, as much as others may refuse to see it. Already Disappeared is not an easy album. It’s often bleak and experimental: Cox’s vocals burst through like distorted, burbling fragments of static, or appear muffled amid the instrumentation. This is a new side of Deerhunter that gives the listener much to contemplate. (Roisin O’Connor)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Sharon Van Etten – Remind Me Tomorrow After a period of tumult, Sharon Van Etten’s fifth album is a reinvention. But beneath its hazy synths and electronics are songs of endurance and inner peace, of settling after a flurry of activity. On Remind Me Tomorrow, written during her recent pregnancy and the birth of her first child, Van Etten dims her spotlight on toxicity and instead casts a warm glow behind the record’s psychic overview. The anxiety and pride of impending parenthood converge on “Seventeen”, a paean to the invincibility and melancholy of adolescence. Addressing a younger version of herself, the 37-year-old sings of the carefree young and their mistrust of those defeated by time. After years making peace with drift and uncertainty, she’s never sounded more sure of anything. (Jazz Monroe)

Ryan Pfluger

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Bring Me the Horizon – Amo BMTH frontman Oli Sykes wants to assert the fragility of the boundary between love and hate. Amo is a way of exploring that, even down to the title itself. Closer “I Don’t Know What to Say” is cinematic in its symphonic drama – perhaps inspired by their 2016 shows at the Royal Albert Hall that featured a full orchestra and choir – and becomes the album’s most moving song. Over urgent, darting violin notes and soft strumming on an acoustic guitar, Sykes sings about the loss of a close friend, building to a hair-raising climax where he screams out the song’s title one last time. Amo won’t satisfy all of BMTH’s fans, but it’s certainly accomplished, catchy and eclectic enough to bring in some new ones. (Roisin O'Connor)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Nina Nesbitt – The Sun Will Come Up, the Seasons Will Change Nesbitt is back with her second LP, switching to a brand of soul and R&B-fused pop that feels bang on time, and suits her far better. The Sun Will Come Up, the Seasons Will Change has slick, polished production from Fraser T Smith (Adele), Lostboy (Anne-Marie), Jordan Riley (Zara Larsson), and Nesbitt herself. Several tracks tap into a Nineties R&B sound that UK women, from Mabel to Ella Mai, are excelling at right now. Assertive tracks “Loyal to Me” and “Love Letter” nod to TLC’s “No Scrubs” and Destiny’s Child’s “Survivor”, but there is vulnerability, too, in the acoustic guitar-led neo-soul of “Somebody Special”, and the tender heartbreak on ”Is it Really Me You’re Missing”. (Roisin O'Connor)

Press image

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Better Oblivion Community Center This self-titled record, a loose but beautifully crafted collection of folk-rock songs, explores the kinds of anxieties intrinsic to the modern age – the longing to be at once noticed and invisible; the paralysing effects of limitless information, and the desire to do good versus the desire to be seen doing good. As if to hammer home their parity, they even largely sing in unison – which might have had a plodding effect if the pair’s voices weren’t so distinct: Bridgers sings with a hazy assurance, Oberst with an emotive tremor. And when Bridgers’ melody does sporadically glide above Oberst’s, it is all the more potent for it. (Alexandra Pollard)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Ariana Grande – Thank U, Next The album is packed with personal confessions for the fans – “Arianators” – to pick over. It lacks a centrepiece to match the arresting depth and space of Sweetener’s “God Is A Woman”, but Grande handles its shifting moods and cast of producers (including pop machines Max Martin and Tommy Brown) with engaging class and momentum. One minute you’re skanking along to the party brass of “Bloodline”; the next floating into the semi-detached, heartbreak of “Ghostin’”, which appears to address Grande’s guilt at being with Davidson while pining for Miller. She sings of the late rapper as a “wingless angel” with featherlight high notes that will drop the sternest jaw. (Helen Brown)

Getty

The best albums of 2019 (so far) James Blake – Assume Form The perma-brilliant James Blake has flooded his fourth album – Assume Form – with euphoric sepia soul and loved-up doo-wop. His trademark intelligence, honesty and pin-drop production remain intact. But the detached chorister vocals of a decade in which he battled depression have thawed to reveal a millennial Sam Cooke crooning: “Can’t believe the way we flow, way we flow, way we flow...” The warm splashes of piano that washed over that song break through the anxious rattle of dance beats on the album’s eponymous opener, the singer so regularly reviewed as “vaporous” promises to “leave the ether, assume form” and “be touchable, be reachable”. His own sharpest critic, he winks at the journalists who’ve called him glacial as he drops from remote, icy falsetto into a richly grained, deeper tone to ask: “Doesn’t it seem much warmer?” (Helen Brown)

Getty

The best albums of 2019 (so far) AJ Tracey – AJ Tracey While he recognises his roots and includes plenty of nods to grime, AJ Tracey's magpie’s eye for a good melody or hook extends far beyond that. With the help of stellar producers like Cadenza (Kiko Bun), Swifta Beater (Kano, Giggs), and Nyge (Section Boyz, Yxng Bane), Tracey incorporates electronic music, rock, garage and even country on his most cohesive work to date. The variety and scale of ambition on this album is breathtaking. Fans will be surprised to discover Tracey sings almost as much as he raps, in pleasingly gruff tones. Each track is a standout, none more so than “Ladbroke Grove”, a hat-tip to classic garage in which Tracey switches up his flow to emulate a Nineties MC. It’s a thrilling work. (Roisin O’Connor)

Ashley Verse

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Sleaford Mods – Eton Alive The album title of the year gives us an image of Brexit Britain trashed by Old Etonians David Cameron, Boris Johnson and Jacob Rees-Mogg, but the fifth studio work from the punk duo has more than social commentary to offer. There’s some of that, as vocalist Jason Williamson skewers documentary-makers who take advantage of the poor in “Kebab Spider” – “the skint get used in loo roll shoes” – but elsewhere this is a record that expands the idea of what Sleaford Mods could be. Andrew Fearn’s beats are no longer just the backdrop, they’re threatening to take over this album. Surprising influences creep in, from Eighties R&B to the Human League, and on “When You Come Up To Me”, Williamson not only sings but there’s a melancholy tone breaking through the anger. “I don’t want to flip the page/ Of my negative script,” he intones on the final track, but there’s just a hint that he does. (Chris Harvey)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Julia Jacklin – Crushing “Do you still have that photograph?/ Would you use it to hurt me?” asks Australian indie rocker Julia Jacklin, against the menacing throb of “Body”. The tension is stormy: imagine a mid-period Fleetwood Mac song, covered by Cat Power. It’s a masterclass in narrative songwriting. Those who fell for Jacklin’s 2016 excellent debut, Don’t Let the Kids Win, will find a continuity of alternative attitude and vintage influences. But there’s a deeper sense of personal connection to anchor Jacklin’s lyrical and melodic smarts. That snare drum keeps a relentless, nerve-snapping pulse throughout, with Jacklin sounding more confident in her contradictions: at once yearning to comfort a lover she’s dumped and then, on “Head Alone”, declaring: “I don’t wanna be touched all the time/ I raised my body up to be mine.” Ah. Shucks. Grunge-rinsed, feminist-flipped, upcycled Fifties guitar an’ all: Crushing is a triumph. (Helen Brown)

Getty

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Little Simz – GREY Area With praise from Kendrick Lamar, five EPs released by the time she was 21, tours with Lauryn Hill, collaborations with Gorillaz and two critically praised albums – including 2017’s excellent concept album Stillness in Wonderland – fans and critics alike wondered what else Little Simz could do to find the kind of mainstream success enjoyed by so many of her male peers. Yet you’d be hard pushed to find a moment over the past few years where Simz has commented on this issue herself. Instead, she’s been busy honing her craft for Grey Area, which sees her land on a new, bolder sound assisted by her childhood friend – the producer Inflo [Michael Kiwanuka’s Love & Hate] – for a record that incorporates her dextrous flow and superb wordplay with an eclectic range of influences. The album takes in everything from jazz, funk and soul to punk and heavy rock, plus three carefully chosen features. (Roisin O'Connor)

Jen Ewbank

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Solange – When I Get Home Solange Knowles has never been coy about the intent behind her music. Beautiful arrangements and seamless production notwithstanding, you get the sense, each time she drop a project, that it serves a distinct, zeitgeist-shifting purpose. This time, with When I Get Home, Solange has effectively given us permission to rest. Echoing similar movements seen in recent years, such as Fannie Sosa and niv Acosta’s “Black Power Naps” exhibition – which speaks to and hopes to remedy the socio-economic problem of higher rates of sleep deprivation among black people – the album has a calming, blissed-out quality, with its layers of sound and enveloping harmonies. And where better to dream than from the comfort of your own digs? Whether it’s in the physical structure of a property that’s shaped you over the years, or in the familiar sounds of the music and culture that your people have crafted, there seems to be a call to return to what is familiar. (Kuba Shand-Baptiste)

Max Hirschberger

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Foals – Everything Not Saved Will be Lost (Part 1) FoalsMerging their asymmetrical early math pop with the deep space atmospherics of Total Life Forever and Holy Fire, plus added innovations – ambient rainforest throbs on “Moonlight”, deadpan EDM on “In Degrees”, Afro-glitch Radiohead on “Café D’Athens” – they’ve created an inspired album of scorched earth new music that, in all likelihood, will only really be challenged for album of the year by Part 2. (Mark Beaumont)

Alex Knowles

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Dave – Psychodrama Tracks are at once astute and deeply personal in how they capture vignettes of everyday life and spin them into important lessons. “Black”, the most recent single from the record, considers what that word means to different people around the world, as well as to Dave. “Voices” has him singing over an old-school garage beat, fighting off personal demons. “I could be the rapper with a message like you’re hoping, but what’s the point in me being the best if no one knows it?” he challenges on “Psycho”, which flips scattershot between beats and moods as though the track itself is schizophrenic. Dave spends Psychodrama addressing issues caused by the generations who came before him. By the end of the album, he sounds like a figurehead for the hopeful future.

Press image

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Sigrid – Sucker Punch At her best, Sigrid throws out precision-tooled high notes like icicle javelins into vast, blue Scandi-produced skies. Then she growls like an Icelandic volcano preparing to disrupt western civilisation until we sort ourselves out. l enjoyed the muted, Afro-tinged authenticity of “Level Up” and the conscious, pasty-girl reggae of “Business Dinners” (on which she refuses to be an industry angel) and I loved the Robyn-esque rush of “Basic” (which sees her yearning to shed love’s complications). Sigrid has a raw energy and emotional briskness that can make you feel like you’re doing aerobics in neon leg warmers atop a pristine mountain. (Helen Brown)

Francesca Allen

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Karen O and Danger Mouse – Lux Prima Lux Prima was born just over a decade ago from a drunken phone call from Karen O to Danger Mouse – real name Brian Joseph Burton – during which the pair vowed they would work on something together. It wasn’t until after O had given birth to her son, though, that recording finally began, and there is a beatific sense of contentment on songs like “Drown”, with its Kamasi Washington-like choirs and stately horns. Danger Mouse is known for genre-hopping collaborations with artists such as Beck, the Black Keys and CeeLo Green, and he applies that approach here, too: the album is an impressive mix of blissed-out synths, psych-rock guitars and trippy hip-hop beats. Lux Prima is an accomplished record – proof that two wildly different minds can work seamlessly together. Maybe drunk-dialling isn’t always such a bad idea. (Roisin O'Connor)

Eliot Lee Hazel

The best albums of 2019 (so far) The Cinematic Orchestra – To Believe This is an ambitious creation, meticulously crafted and assembled. For a start, the range of guest performers is a cornucopia of contemporary soul and hip-hop collaborators: vocalists Moses Sumney, Roots Manuva, Heidi Vogel, Grey Reverend and Tawiah; strings player Miguel Atwood-Ferguson, and keyboardist Dennis Hamm – both of whom have worked with Flying Lotus and Thundercat. Ma Fleur was emotive and piano-led, its themes of mortality and the passage of life captured so evocatively in the Patrick Watson collaboration “To Build a Home” – which went on to soundtrack every TV show from Grey’s Anatomy to Orange is the New Black. To Believe, however, feels more expansive in reach. (Elisa Bray)

B+

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Lucy Rose – No Words Left Rose – who found fame in the UK’s indie-folk scene as an unofficial member of Bombay Bicycle Club in 2010, only to walk away amid the band’s growing hype – is darkly compelling on No Words Left. Assisted by producer Tim Bidwell, who worked on Rose’s last record Something’s Changing, she sounds braver than she ever has before. There are moments that recall her Communion labelmate Ben Howard, on his latest album, Noonday Dream, and others that nod to the quiet stoicism of Joni Mitchell and Neil Young. (Roisin O'Connor)

Getty

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Nilufer Yanya – Miss Universe The record is loosely conceptual insomuch as it’s punctuated with mock adverts for “WWAY HEALTH, our 24/7 care programme”. But don’t be put off: Miss Universe is a brilliant collection of songs, an expansive melange of indie, jazz, pop and trip-hop that flits between a lo-fi sparseness and something The Strokes would play. Yanya – who is of Turkish-Irish-Bajan heritage – grew up in London on a mix of Pixies, Nina Simone, The Libertines and Amy Winehouse, and this unlikely combination is certainly reflected in the sound. (Patrick Smith)

Molly Daniel

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Jenny Lewis – On the Line Here, Lewis does what she does best: adds the glossy sparkle of Hollywood and a sunny Californian sheen to melancholy and nostalgia, with her most luxuriantly orchestrated album yet. Even when she’s singing, “I’ve wasted my youth”, it’s in that sweet voice, with carefree “doo doo doo doo doo doos”, and at a pace that’s so upbeat that it masks the sentiment. It’s a bittersweet mourning of her past. (Elisa Bray)

Press

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Ty Segall – Deforming Lobes Comprising songs from Segall’s eclectic (that’s putting it lightly) catalogue and performed by him and the Freedom Band (Mikal Cronin, Charles Moothart, Emmett Kelly, and Ben Boye), the album is delightfully short and sweet. It is certainly a drastic switch-up from Freedom’s Goblin (2018), which had 19 tracks and ran for 75 minutes. Opener “Warm Hands”, from Segall’s self-titled 2017 LP, is essentially an epic jam; he grinds out fuzzy distortion and squalling riffs for a solid nine and a half minutes with a gleeful lawlessness. “Love Fuzz”, which serves as the opposing bookend at the album’s close, is even wilder. This isn’t a “best of” selection – the band simply chose the tracks out of which they got the biggest kick. Deforming Lobes is unpredictable and invigorating – the best representation of Segall’s restless creativity to date, not to mention the most fun to listen to. (Roisin O’Connor)

Getty

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Weyes Blood – Titanic Rising If you want to know how hard it is to categorise Titanic Rising – the enthralling fourth album from Weyes Blood – look no further than the American musician’s own attempt to do so. It is, she says, “The Kinks meet the Second World War, or Bob Seger meets Enya.” Neither of those is a particularly accurate description, but they do at least fit the album’s refusal to loiter in any one genre. Slide guitars give way to violas, which usher in eerie synths. Organs crop up throughout, evoking both Renaissance music and a fairground attraction. The fragmented strings in “Movies”, a song about the falsities of Hollywood romance, recall the chaotic minimalism of Arthur Russell. And then there’s that voice – at once warm and haunting, controlled and untethered. It’s no wonder she’s lent it to the likes of Perfume Genius, Drugdealer and Ariel Pink: it adds a touch of profundity to everything it meets. Titanic Rising isn’t Bob Seger meets Enya. It’s better. Alexandra Pollard

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Chemical Brothers – No Geography Tension aside, there’s a great sense of fun here. The title track is pure euphoria, as restless synths of a Utah Saints or Orbital rave break into swelling bass and melody. And they create the full club experience with “Got to Keep On”, on which the four-to-the-floor beat, funky rhythm guitar, sweet backing vocals and chiming bells make way for the simple sounds of happy party-goers; just as the anticipation builds, so does the instrumentation into a hypnotic crescendo. It’s masterful production. (Elisa Bray)

Press

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Anderson .Paak – Ventura Six months after the release of Oxnard, Anderson .Paak returns with another Dr Dre-produced record, Ventura. Where the former was overflowing with choppy, experimental sounds, guest appearances and clumsy attempts at Gil Scott Heron-esque revolutionary lyrics, the sequel – recorded around the same time – streamlines .Paak’s sound, making for a tightly packaged, melodic and danceable album. Rather than being an album of Oxnard offshoots, Ventura instead borrows heavily from .Paak’s consistently brilliant 2016 record Malibu, itself a fresh slice of soulful funk. The singer croons over disco-infused, Quincy Jones-inspired trumpets on “Reachin’ 2 Much”, masterfully interplays vocals from Smokey Robinson with violin flourishes on “Making it Better”, and playfully raps about global warming on “Yada Yada”. As .Paak sings on “Winners Circle”, “They just don’t make them like this anymore”. Considering how few artists have such command of their craft as .Paak, he’s not wrong. (Jack Shepherd)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Loyle Carner – Not Waving, But Drowning Two years after the release of his Mercury Prize-nominated debut Yesterday’s Gone, the south London hip-hop artist unveils its follow-up, Not Waving, But Drowning. And if any two records could portray how quickly someone can grow from a boy to a man, it’s these. Familiar faces and themes serve as his trademarks. Fellow Mercury Prize nominee Jorja Smith and winner Sampha sound like old friends in their guest spots – they fit comfortably into Carner’s landscape, built from classic hip-hop beats and warm piano loops. Over all of it, he raps with an easy flow in gruff yet honeyed tones. Above all, he is conscious of what family means to him, and so bookends the album with a poem from him to his mother Jean, and one from his mother to him. Not Waving, But Drowning has an emotional intelligence that shows just how strong Carner is when he’s at his most vulnerable. (Roisin O'Connor)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Lizzo – Cuz I Love You No one could accuse Lizzo of holding back. Not when it comes to her voice – which is raw and rowdy, so laden with personality even the vulnerable moments are a joy to listen to – and certainly not when it comes to her message of unabashed self-love. That’s the predominant theme of the singer / rapper / flautist-extraordinaire’s hugely likeable third album, Cuz I Love You. When Lizzo played Coachella earlier this week, her set was plagued by technical problems. “When I’m headlining next time,” she announced, “I’m gonna need my motherf**king ears to work.” Judging by the strength of her third album, that might not be such an implausible assumption. (Alexandra Pollard)

Luke Gilford

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Fat White Family – Serfs Up! It seems as likely as Old Man Steptoe dining with the Rees-Mogg, but this new tactic of burying their confrontational gruesomeness beneath a veneer of alt-rock respectability for album three works well for Fat White Family. Drenched in chamber strings and celestial harmonies, the plush yet sinister “Oh Sebastian” could be Pet Sounds selling its soul to the devil. “Fringe Runner” is so sleek and funksome it could be a New Romantic “White Lines (Don’t Don’t Do It)”; “Kim’s Sunsets” is a piece of refined cosmic reggae resembling a blissed-out “Bankrobber”. Tarantino bossa novas and Velvets drones are all imbued with a luminous, cultured seediness, like the entire Cannes Film Festival owning up to its social diseases. Wonderfully unsettling. (Mark Beaumont)

Morbid Books

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Cage the Elephant – Social Cues On Cage the Elephant’s fifth album, Social Cues, frontman Matt Shultz reacts to the breakdown of his marriage and the loss of three close friends. He undergoes a kind of Jekyll and Hyde transition through the 13 tracks, the result of which is the band’s best work to date. Assisted by producer John Hill, whose previous credits include co-writing Portugal. The Man’s mega-hit “Feel it Still”, the Kentucky-formed, Nashville-based Cage the Elephant remain faithful to their neo-soul influenced brand of garage rock but move to something darker and far more visceral. Single “Ready to let Go” is by far the most explicit – a moody swamp-rock jam where Shultz comes to terms with his impending divorce. “House of Glass” is a sequence of frenzied mutterings with a buzzsaw guitar cutting through his attempts to convince himself of love’s existence. Social Cues is an album where Shultz bares his soul, and apparently shakes off a few demons in the process. (Roisin O’Connor)

Neil Krug

The best albums of 2019 (so far) SOAK – Grim Town SOAK reaches to outsiders once again on her new album. Musically, she’s developed her arrangements and become bolder, too. The tempo-shifting country-folk song “Get Set Go Kid” layers guitar, keys and subtle, harmonising backing vocals, unexpectedly building towards a cacophony of syncopated piano and saxophone. “Crying Your Eyes Out” appears to be a sombre piano ballad until it ramps up the angst with plaintive vocals, conjuring up a storm with swirling rhythms. On the melancholy, gently strummed guitar and piano-led “Fall Asleep, Backseat”, Monds-Watson reflects on pretending to sleep as her parents make the painful decision to divorce. In a way, Grim Town portrays the journey from adolescence into young adulthood – with all the introspection, resignation and wide-eyed forays into love that entails. (Elisa Bray)

Charlie Forgham Bailey

The best albums of 2019 (so far) The Cranberries – In the End There’s a cruel irony that the release of The Cranberries’ final album should come just a week after journalist Lyra McKee was shot dead by the New IRA during a riot in Londonderry. “Zombie” was a protest song written by the band’s late frontwoman Dolores O’Riordan after two children were killed by IRA bombs – was released. She was deeply affected by the deaths, and would no doubt have been devastated by recent events in Northern Ireland as well. “Wake Me When it’s Over”, the third track on In the End, could be “Zombie”’s twin. On it, O’Riordan, who recorded demos for the album’s 11 tracks before her death in January last year, sings: “Fighting’s not the answer/ Fighting’s not the cure/ It’s eating you like cancer/ It’s killing you for sure.” The band have spoken about how O’Riordan was singing about leaving many of the negative things in her life behind. It sounds like The Cranberries found some kind of closure in this last record. Hopefully fans will, too. (Roisin O’Connor)

(Photo credit should read GUILLAUME SOUVANT/AFP/Getty Images)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Aldous Harding – Designer On her third record, Aldous Harding combines the gothic folk of her self-titled 2014 debut with the dramatically intimate tones of her follow-up album Party. The New Zealand artist seems to derive a particular glee from unsettling her audience. Her Medusa’s stare – witnessed at her live shows as well as in her music videos – has become the stuff of legend. She switches her vocal style song to song, moving from a lilting croon on “The Barrel” to the quirky elocution of the title track. She joins forces once again with PJ Harvey collaborator John Harvey, and also enlists Welsh musicians Stephen Black (Sweet Baboo) and Huw Evans (H Hawkline) plus Clare Mactaggart on violin, giving Designer a generously textured feel. It’s layered with whimsical flutes, intricate guitar picking and sombre bass lines that meander with casual abandon. At an age where the pressure is on to have everything worked out, Harding sounds delightfully free. (Roisin O’Connor)

Claire Shilland

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Big Thief - UFOF Big Thief’s frontwoman Adrianne Lenker has an uncanny ability to make you feel like you’re in on a secret. Her whispering, spectral delivery and deeply personal lyrics are the key to this. Even on the band’s third album UFOF, with an audience that has grown exponentially in the past few years, the songs are still immensely intimate affairs. Often, Lenker offers the same kind of symbolic fatalism as the poetry of Christina Rosetti: “We both know/ Let me rest, let me go/ See my death become a trail/ And the trail leads to a flower/ I will blossom in your sail,” she sings on “Terminal Paradise”. This deathly intrigue is drawn from Lenker’s own personal traumas, which she successfully spins into something that feels universal. But you don’t come away from this record feeling downcast. It’s more a reminder of how fleeting yet beautiful life is, and an appeal to make the most of it. (RO)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Collard - Unholy On his debut album, the 24-year-old Collard mixes sultry jams that recall the electronic funk of MGMT with nods to the greats: Prince, James Brown, Led Zeppelin and Marvin Gaye. Throughout, Collard exhibits his extraordinary voice, which swoops to a devilishly low murmur or soars to an ecstatic falsetto. Guest rapper Kojey Radical takes on the role of preacher for “Ground Control”. There’s a sax on “Sacrament” that’s loaded with longing, while the grunge-gospel stylings of “Merciless” offer ominous guitars and Collard’s reverent croons. On the lustful “Hell Song” he sings “less is more… but more is good”. You’re inclined to agree with him. (RO)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Carly Rae Jepsen - Dedicated Dedicated covers the full, but generic, spectrum of relationships: dizzying love, lust, and break-ups. But whether she’s pining for the return of a former love in the funky disco banger “Julien”, or singing about masturbating post-break-up in lead single “Party For One” (“I’ll be the one/ If you don’t care about me/ Making love to myself/ Back on my beat”), the vibe remains positively jubilant. The euphoric, Eighties synth-laden “Want You in My Room” is most distinctive, both vocally and melodically, and was co-written and produced by Jack Antonoff, indie tunesmith for fun. and Bleachers. But “Party For One” remains the album’s highlight, harnessing the bouncy energy of Jepsen’s breakout hit. It is the perfect upbeat end to an album of polished pop. Perhaps this will put her at the top where she belongs. (Elisa Bray)

Getty Images for Spotify

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Tyler, the Creator - IGOR “I don’t know where I’m going,” Tyler, the Creator begins on the song “I THINK”. “But I know what I’m showing.” The US artist’s words ring true throughout his fifth studio album, IGOR, where he adopts the dark and twisted mutterings of the Frankenstein character from which the record gets its name. The production here is superb. Tyler has never been one for traditional song structure, but on IGOR he’s like the Minotaur luring you through a maze that twists and turns around seemingly impossible corners, drawing you into the thrilling unknown. (RO)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Flying Lotus - Flamagra It’s been a long wait for Flying Lotus’s new album. In fact, the LA producer has been masterminding Flamagra for the past five years – snatching moments between collaborating with Kendrick Lamar on To Pimp a Butterfly, directing and writing the comic horror movie Kuso, producing much of Thundercat’s Drunk and growing his Brainfeeder label. But it was worth the wait. Flamagra – a playful yet melancholic, skittish yet meditative 67 minutes of cosmic genius – is one of Flying Lotus’s most accessible releases. A 27-track masterpiece, the album features the likes of Anderson .Paak, Little Dragon, David Lynch, and Solange, and serves up a hot, textural mix of hip-hop, psychedelia, funk, soul, jazz and electro. (Ellie Harrison)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) The Amazons - Future Dust A heftier sound is never at the cost of melody, which shines through in Thomson’s vocals, the rest of the band’s backing falsetto, and the searing blues grooves stamped all over Future Dust. Those qualities are captured nowhere more satisfyingly than on “25”. “All Over Town” is their singalong anthem, neatly positioned in the middle to ease the pace. If there’s a twist here, it’s final song “Georgia”, which takes its classic-rock licks straight out of the Eagles’ songwriting book. But this is an album that shows a band who’ve grown stronger and unafraid to flex their muscle. (Elisa Bray)

Alex Lake

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Skepta - Ignorance is Bliss In keeping with the relatively restrained guest spots, it’s heartening just how much Skepta has rejected overloading Ignorance is Bliss with high-profile producers, preferring instead to burrow into his own aesthetic. There’s no attempt to chase someone else’s wave here; no token drill, afroswing or trap beats to satisfy playlist algorithms. Instead, his cold grime sonics are rendered down to their no-frills essentials – brutalist blocks of sad angular melodies and hard, spacious drums. The result is a quintessentially London record, as dark and moody as it is brash and innovative. “We used to do young and stupid,” Skepta concludes on “Gangsta”. “Now we do grown.” (Ian McQuaid)

Boy Better Know

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Bruce Springsteen - Western Stars Bruce Springsteen seems to have told almost every tale in the grand old storybook of American mythologies, except perhaps one: a wide-eyed Californian dreamer finds the Golden State turns sour and flees back east, to some romantic speck of a town, to pine and rehabilitate. It’s the classic pop plotline of Bacharach and David’s “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?”, and it’s a tale Springsteen taps repeatedly here, on his sumptuous, cinematic 19th album, which is nothing short of a late-period masterpiece. Springsteen’s sublime portraiture of the American struggle – his protagonists walking with him through the ages of life as he goes – endures. “Hitch Hikin’” and “The Wayfarer” are both charmed odes to the lost and rootless. Where most rock superstars sink into trad tedium by 69, Springsteen is still crafting sophisticated paeans of depth and illumination, a rock grandmaster worthy of the accolade. A must-have for anyone who has a heart. (Mark Beaumont)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Mark Ronson - Late Night Feelings A revolving door of female vocalists (A-listers, indie darlings like Angel Olsen and unsung songwriters) deliver heartbroken lines over big, shiny beats and synths. The emotional cohesion the record loses in its shifting cast of singers/songwriters/genres it makes up in DJ-savvy textural variety. You’ll already have heard “Nothing Breaks Like a Heart”, on which Miley Cyrus channels the quavering, fearless bluegrass spirit of her godmother Dolly Parton over a briskly plucked guitar. Ronson’s production is so sharp that you all but see the steel strings rise like a hi-definition hologram from your speakers. It's a style that makes fans of vintage engineering wince, but snags the ear like a fishhook. And those quicksilver hooks just keep coming. (Helen Brown)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) The Raconteurs - Help Us Stranger Help Us Stranger reaches all corners of guitar rock: funky Detroit garage (“What’s Yours Is Mine”); country soul (“Somedays (I Don’t Feel Like Trying)”); psych (a cover of Donovan’s “Hey Gyp (Dig the Slowness)”); blues and bluegrass (“Thoughts and Prayers”). A cornucopia of instrumentation is woven into its brisk 42-minute yarn. From frenetic opener “Bored and Razed”, you can sense the compelling chemistry between Benson and White playing out on stage as the duo harmonise or sing in unison, and White strikes frenzied riffs alongside Benson’s melodic guitar chops. The energy here is thrilling, the strong rhythm section provided by former Detroit garage band The Greenhornes’ bassist Jack Lawrence and drummer Patrick Keeler. The bass and riff-driven “Now That You’re Gone” feels stripped back by comparison; it’s perfectly crafted. Help Us Stranger has been a long time coming, but it was worth the wait. (Elisa Bray)

David James Swanson

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Hot Chip - A Bath Full of Ecstasy When Hot Chip achieved chart success with their second album, 2006’s The Warning, it seemed more like a happy coincidence than a sign they were conforming to current pop trends. Since then, they've released a string of consistently great albums, from 2008’s Made in the Dark (featuring their only Top 10 single to date, “Ready for the Floor”) to this, their seventh and best record, A Bath Full of Ecstasy. Philippe Zdar – one half of the French duo Cassius and producer for the likes of MC Solaar and Phoenix – helps the band reconcile their house and hip-hop influences. The late musician had a free-spirited approach that suits Hot Chip on the psychedelic “Clear Blue Skies”, and there are nods to early Nineties French house via the glitchy funk and vocoder effects of “Spell” (an album highlight).. For all its glimmering synths and the robotic pathos of Taylor’s idiosyncratic vocals, this is a record with both heart and soul. (Roisin O'Connor)

Ronald Dick

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Banks – III The record frequently switches in tone: Banks can be both formidable and vulnerable, accusatory or filled with regret. “Gimme” demands sex and refuses to be shamed for it; “Contaminated” mourns a toxic relationship that can’t be saved; and “Stroke” is a bitter riposte to a man emulating the Greek figure Narcissus – laid over a funk guitar riff. III is Banks’s most cohesive album to date because she’s no longer restricting herself to exploring one feeling at a time. The way she has structured this record takes the listener through the complicated yet nuanced emotions of a woman who has recently learnt to accept everything she feels. She embraces her pain, and as a consequence is able to let it go. (Roisin O"Connor)

Press image

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Mini Mansions – Guy Walks into a Bar Mikey Shuman shares vocal duties with Tyler Parkford; his voice falls somewhere between the sleazy drawl of his QOTSA bandmate Josh Homme and Alex Turner’s more adenoidal tone on opener “We Should Be Dancing”. With tracks that frequently dart from sprawling, psychedelic pop to scuzzy post-punk and rock references, the record has a superb dynamic that holds the listener’s attention, while the band navigate through a single, tumultuous relationship. By the end of all that, you feel like they deserve a pint. (Roisin O'Connor)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Marika Hackman – Any Human Friend Hackman’s debut album, 2015’s We Slept At Last, was a gentle, unprovocative affair – though if you listened closely, the dark, sexual energy that convulses through her current sound was already there. Her second, I’m Not Your Man, was scuzzier and more explicitly queer – a road she continues down with Any Human Friend, a blunt, bold album on which Hackman’s beatific voice sits atop methodically messy instrumentals. Written in the aftermath of Hackman’s split from fellow musician Amber Bain – aka The Japanese House, who released her own reflection on their break-up on her debut album Good at Falling – Any Human Friend is a satisfyingly dismal affair that is certainly not suitable for the four-year-old who inspired it. (Alexandra Pollard)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Slipknot – We Are Not Your Kind Frontman Corey Taylor, who had just emerged from a toxic relationship when recording this album, addresses feelings of belittlement and inadequacy with unflinching honesty and some of his best vocal work in years. Over the Celtic influences of “Solway Firth” (at one point, he seems to attempt some Cockney screamo) he issues a blistering riposte to the people he holds responsible for his negative mindset. Critics may question how relevant Slipknot are in 2019. The pummelling force of We Are Not Your Kind should be enough to silence them – this may be one of the band’s most personal records, but the rage they capture is universally felt. (Roisin O'Connor)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Sleater-Kinney – The Center Won't Hold There’s an increased anxiety, both corporeal and emotional, running through The Center Won’t Hold, a pent-up desire to break free from something – though they never seem quite sure what. “Disconnect me from my bones, so I can float, so I can roam,” sings Brownstein – her singular voice all yelps and creaks – on “Hurry On Home”. On “Reach Out”, Tucker begs, her voice a little sleeker than Brownstein’s but no less commanding, “Reach out and see me, I’m losing my head.” Quietly discordant piano ballad “Broken” pays tribute to Christine Blasey Ford, the woman who accused supreme court judge Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault: “Me, me too, my body cried out when she spoke those lines.” The Center Won’t Hold is a reference, it seems, to the 1920 WB Yeats poem “Second Coming”: “Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold.” If this is Sleater-Kinney falling apart, then what a beautiful collapse it is. (Alexandra Pollard)

Nikko LaMere

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Rapsody – Eve The overarching sound, production and instrumentation on Eve are outstanding. Produced by Rapsody’s long-time collaborator and mentor 9th Wonder, the record samples cuts from Herbie Hancock’s “Watermelon Man” (“Whoopi”) and Phil Collins’s “In the Air Tonight” (“Cleo”), offers a smooth R&B joint with “Aaliyah” featuring the late singer’s ghostly backing vocals, and includes an interlude that is “an ode to the black woman’s body”. As on Laila’s Wisdom, Eve conveys Rapsody’s natural feel for funk – “Michelle” (Obama) bounces in on a jaunty piano riff – but other tracks, such as closer “Afeni”, are pure soul. Nina Simone said an artist’s duty, “as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times”. This is precisely what Rapsody has done – in the most resonant way possible.

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Taylor Swift – Lover Swift has a habit of putting her worst foot forward. The album’s lead single, “Me!”, is peppy and poppy in all the wrong ways, a rictus grin of a song that rings hollow. Thank goodness that the rest of the album is nothing like that. Perky opening track “Forgot That You Existed” is a syncopated snigger, on which Swift shrugs off old grudges and breathes a sigh of relief in doing so. “Something magical happened one night,” she sings. “I forgot that you existed. And I thought that it would kill me, but it didn’t.” The title track, meanwhile, is poignant and unfussy, a reminder of Swift’s ability to distil infatuation into something specific and universal. (Alexandra Pollard)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Sheryl Crow – Threads One could argue that there’s too much eclecticism here – that if this really is Crow’s final LP, she perhaps could have gone for something with a more singular sound. But then it wouldn’t be a Sheryl Crow album. She sings about the fear of the unknown on “Flying Blind” – her steely determination on this record has you believing that she’ll take the leap regardless. (Roisin O'Connor)

Dove Shore

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Common – Let Love There’s more of a soul influence here – “HER Love”, the counterpoint to his 1994 track “I Used to Love HER”, benefits from the gospel-like vocals of Daniel Caesar and Dwele, while “Memories of Home” skitters over a muffled bass and Common’s recollections of his past – including an incident where he was molested by a family member. Where Black America Again was notable for its sharp, observational urgency, Let Love feels far more personal, and softer in tone. Common’s optimistic nature gives it an uplifting vibe, and while closer “God is Love” is gently critical of people who use their religion to persecute others, the message is one of learning from our mistakes. It couldn’t be more timely. (Roisin O'Connor)

File image

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Lana Del Rey – Norman Fucking Rockwell! This is Del Rey at her most assertive – personally, if not politically. Those hoping for a barbed protest record in keeping with Del Rey’s newfound public activism (last year she called President Trump a “narcissist” who “believes it’s OK to grab a woman by the pussy just because he’s famous”) will be disappointed. But it is gratifying to hear her take control. Aside from “Happiness Is a Butterfly”, that is. “If he’s a serial killer, then what’s the worst that can happen to a girl who’s already hurt?” she asks. Crikey. “We were so obsessed with writing the next best American record,” sings Del Rey on “Next Best American Record”. This isn’t it, but it’s pretty great all the same. (Alexandra Pollard)

Getty Images

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Ezra Furman – Twelve Nudes Assisted by veteran producer John Congleton (St Vincent, John Grant), he channels the spirit of David Bowie and Iggy Pop. He screeches over distorted “ooh oohs” via The Rolling Stones’s “Sympathy for the Devil” on opener “Calm Down aka I Should Not Be Alone”. “Transition from Nowhere to Nowhere” is sung in a Ziggy Stardust croon, while “Rated R Crusaders” shows Furman exploring his Jewish identity in the era of the Israel/Palestine conflict. His sardonic yet sensitive approach to gender and sexuality on “I Wanna Be Your Girlfriend” is a reminder, if one was needed, why he was so well-suited to scoring the soundtrack for Netflix’s Sex Education. Each song feels personal yet relatable – the deep-rooted despair felt on “Trauma” at the sight of wealthy bullies rising to power is a universal one, as is the sense of liberation in just letting go on “What Can You Do But Rock n Roll”. Twelve Nudes is Furman’s most urgent and cathartic record to date. (Roisin O'Connor)

Jessica Lehrman

The best albums of 2019 (so far) The Black Keys – Let's Rock! If Brothers, their brawny album from 2010, turned the pair into serious rock contenders, then 2011’s El Camino cemented their reputation. Yet neither can claim to be as fiendishly catchy as Let’s Rock, a record that can scarcely sit still. On opener “Shine a Light”, the riffs are big, the momentum irresistible, with frontman/guitarist Dan Auerbach layering scabrous licks over AC/DC-like chords. Backing singers Leisa Hans and Ashley Wilcoxson add texture to the grooving “Lo/Hi”, while the languid “Sit Around and Miss You” is Stealers Wheels by way of the Deep South. Listen to the melodic harmonies in “Tell Me Lies” and it’s not just the lyrics that’ll remind you of Fleetwood Mac. Indeed, so heavily do The Black Keys wear their influences that the record – their ninth – risks coming across like Stars in Their Eyes: The Rock Edition. But if this is genre pastiche, it’s genre pastiche done with skill and savvy. (Patrick Smith)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Thom Yorke – ANIMA The tones here are stark and bleak, compared to the claustrophobia of 2014’s Tomorrow’s Modern Boxes. You can hear his paranoia in the stuttering techno opener “Traffic”, which channels the heady grooves and pulses of electronic artist Floating Points (who, with his neuroscience background, seems like an entirely fitting reference point). Yorke often tends to make his most explicit political comments outside of music: in a recent interview, for example, he complained about how discourse has regressed, referring to British and American politics as “a Punch and Judy show”. But there are moments here where you feel his rage: “Goddamned machinery, why don’t you speak to me?/ One day I’m gonna take an axe to you,” he growls on “The Axe”. (Roisin O'Connor)

Greg Williams

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Nas – The Lost Tapes II There are plenty of surprises, like Swizz Beats singing on “Who Are You” against elegant violins that recall a Kamasi Washington composition. “Adult Film” features a gorgeous piano riff; the Pete Rock-produced “The Art of It” has a delicious funk vibe; “It Never Ends” comes full circle via a bright piano loop. Where a full album produced by Kanye West (2018’s Nasir) didn’t pan out – perhaps because West’s perfectionism was a bad fit for Nas’s penchant for procrastination – “You Mean the World to Me” sounds like it would have been a standout on that record had it not been abandoned on the cutting-room floor. Now it’s a standout on this album. Maybe Nas never really lost it, but The Lost Tapes II sounds like an artist rediscovering his love for hip hop in the most joyous and satisfying way. It’s hard not to consider his timing for this release, just three months since the 25th anniversary of Illmatic. It feels a lot like a third coming. (Roisin O'Connor)

Rex

The best albums of 2019 (so far) The Flaming Lips – King's Mouth For all the album’s eccentricities, the vibe is earnest fairytale rather than tongue-in-cheek – save for the sound of a strangled feline mirroring the lyrics “when you stepped on your cat” on “How Many Times”. Epic highlight “Electric Fire” and celestial album-closer “How Can a Head” capture Coyne at his most wistful. The latter is a wide-eyed, strings-laden gem, its childlike, questing lyrics poignant whatever your age. Just as the preceding art installation invited viewers to enter its vast head of LED lights and wonder, this album does the same. (Elisa Bray)

Warner Bros Records

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Bat for Lashes – Lost Girls Given our current preoccupation with the Eighties, you could argue that Lost Girls is hardly breaking new ground – and yes, nostalgia is a fairly generic formula. But listened to as a whole, the album positively thrums with sonic invention, managing to feel both fresh and full of intrigue. Khan once again demonstrates a knack for uncanny storytelling. Three of her past albums have been nominated for Mercurys; expect this to make it four. (Patrick Smith)

Jen Ewbank

The best albums of 2019 (so far) MUNA – Saves the World MUNA might not be a household name yet, but their influence runs through the charts like a stick of rock these days. Listen to Katy Perry’s summer smash “Never Really Over”, or Taylor Swift’s feminist clap back “The Man”, and you’ll hear the same dense, sticky synths and brawny beats that the emo-pop trio have been honing for the past three years. Their debut album, 2017’s About U, was raw, poignant and just the ride side of melodramatic, queering the mainstream, one sad-pop anthem at a time. If there’s any justice, its follow-up, Saves the World, should see MUNA joining the ranks of those who have brazenly borrowed their sound. Lead single “Number One Fan” banishes intrusive thoughts – “Nobody likes me and I’m gonna die” – just in time for a lavish, self-celebratory chorus, one part earnest, one part tongue-in-cheek.(Alexandra Pollard)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Pixies – Beneath the Eyrie Tales of witchy curses (“On Graveyard Hill”) and spirit reincarnation (“Daniel Boone”) feel like they’ve been dug up from ancient folklore, and capture classic-Pixies menace and ghoulish spirit. Over the album’s 12 tracks, ghostly organs and minor-key guitar-picked sequences help to conjure this dark, Gothic vibe. Yet for all its darkness, Beneath the Eyrie is brimming with the kind of melody that we expect from these indie-rock giants from the late Eighties. “Ready for Love” is a melancholy ballad with harmonising vocals from bassist Paz Lenchantin (Kim Deal’s now-permanent replacement), while lead single “Catfish Kate” – a tale of a woman battling a catfish in a river told by Black Jack Hooligan – is a rock hit in waiting. (Elisa Bray)

BMG

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Jenny Hval – The Practice of Love This endlessly fascinating artist’s seventh, full-length, album The Practice of Love is just as considered as 2016's Blood Bitch, examining one’s role in humankind and on Earth, and probing that favourite of pop-song themes: love. But where the 2017 Nordic Music Prize-winning Blood Bitch was packed with visceral imagery and disarming sonics, the themes of The Practice of Love are encased in a warm cocoon of poetry, blissed-out circling synths and trance-like Nineties beats. (Elisa Bray) There’s an interior dialogue throughout, which is sometimes more intriguing than musically engrossing. Take the title track, whose spoken-word monologue morphs into a recorded conversation in which a woman discusses how childlessness in her late thirties affects her place in society, over the sparsest electronica.

Tore Setre

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Metronomy – Metronomy Forever This is Metronomy at their most ambitious and pleasurably weird. As with the dreamy “Upset My Girlfriend”, which speaks of a man about to propose to his partner despite the fight they’re in, it’s an album stranded somewhere between pure joy and unexplainable sadness; like slapping on a false smile despite feeling miserable, and recognising how much it helps in the moment. (Adam White)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Charli XCX – Charli Listening on headphones, I was reminded of the late French designer Janet Laverriere. Born in 1909, she was still a powerful, playful force when I interviewed her for this paper in her eighties. She banged a cast iron radiator with a spoon to celebrate the echoes and curves of essential pipework: “I put all the hard plumbing on the outside. In kitchens, in bathrooms, I am feminist, evidemment!” I felt that spirit through almost every the clink, clunk, crash and molten flare of this album. It ends with another Sivan collaboration: “2099”. “I’m Pluto, Neptune, pull up, roll up, f**k up, future, future...” they intone. Charli’s always so much cooler when she swaps the people-pleasing nostalgic for the free-wheeling futuristic. (Helen Brown)

Getty/Pandora

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Sam Fender – Hypersonic Missiles Fender drew plenty of early comparisons to Bruce Springsteen – on Hypersonic Missiles they’re entirely warranted, as much for the instrumentation as the lyricism and his vignettes of working-class struggle. There are sax solos (more than one), and pounding rhythms that make you want to jump in a car and drive down a highway at sunset, and blistering electric guitars next to classic troubadour acoustics. He has Springsteen’s rousing holler, and the early indications of someone who could be the voice of a generation – not because he wants to be, but because he sees things and understands. (Roisin O'Connor)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Liam Gallagher – Why Me? Why Not. Why Me? Why Not. is enjoyably defiant, Gallagher embodying a settled and contented aura. “Gotta live for something besides yesterdays,” Gallagher snarls on “Be Still”. The downbeat “Once” forgoes easy Noel-bashing for a mournful glance at the years when the pair were still speaking (“I remember how you used to shine back then... but you only get to do it once”). And “Now That I’ve Found You” is even somewhat sickly-sweet in tone, a cheery tribute to his daughter Molly, whom he met for the first time when she was 21. “I know it’s late for lullabies, but the future is yours and mine,” he sings, alongside upbeat whoops and Radio 2-friendly guitars. (Adam White)

The best albums of 2019 (so far) Brittany Howard – Jaime The album takes a deep, contemplative breath on “Short and Sweet”, which is exactly what it promises, a Grace Jones-like ballad on which Howard’s voice takes precedent over inconspicuous guitar, and the background hisses like an old vinyl. On “He Loves Me”, she grapples with maintaining a relationship with God when she’s long since stopped going to church. There’s no track on Jaime that is likely to make waves – not in the same way as some of the better-known Alabama Shakes tracks, such as “Hold On” or “This Feeling” (the latter of which was recently used to remarkable effect in the final scene of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag). But what lovely ripples it makes. (Alex Pollard)

Brantley Gutierrez

Del Rey’s fascination with film noir is relevant. The genre rose to prominence in the Thirties and Forties, as the Second World War shifted women’s place in the culture. While magazine illustrator Norman Rockwell was painting patriotic images of hearty female factory workers like “Rosie the Riveter”, Hollywood was turning out films which portrayed these newly ambitious, independent women (like Turner’s character Cora in The Postman Always Rings Twice ) as a danger to men. With cigarettes between their lips and guns in their handbags, they resisted the conventional roles as good wives and mothers and the movies punished them with brutal deaths. Yet their wit, strength and sexiness have outlived their fictional demises in the cultural memory.

Meditating on them in the 21st century, Del Ray created a pop persona who looked and sounded like a dangerous noir heroine, but embraced the submissive attitude of the Forties housewife. Although she said feminism didn’t interest her, she provoked an uncomfortable debate about the ways in which society still divides us into Madonnas and whores – on Twitter as on vintage celluloid. Her songs laid bare the dangerous seductions of either option. She was sharp and unflinchingly funny about how our sexuality was marketed back at us: “My pussy tastes like Pepsi Cola…” she sang.

On her breakthrough single, “Video Games” (2011), she wallowed in surrender to a man who ignored her. There were harps and funeral bells. A few years earlier, on the other side of the Atlantic, Britain’s Amy Winehouse had done something similar, channelling the man-mad melodrama of the Sixties, falling out of bars without her shoes while telling the press all she wanted to do was become a good wife and mother. She died three months before the release of “Video Games”.

Between them, they created the perfect soundtrack for a confusing period during which women were buying into Cath Kidston’s retro “pinny porn” and devouring EL James’ BDSM bestseller, Fifty Shades of Grey (2011). In retrospect, maybe it was a time when women felt safe enough to explore their totally normal masochistic fantasies the way men could. (Think of Ryan Adams’: “Come pick me up/ F**k me up/ Steal my records…”, although Adams is another musical hero I’m being forced to re-evaluate.) And it was a time when many women of Del Rey’s privilege and generation – perhaps understandably – didn’t know what to make of, or take from feminism. It was 2014 when Del Rey said it didn’t interest her.

But that mood began to change in 2016 as the #MeToo movement revealed abusers still controlling the culture and Donald Trump was elected. The empowered Beyoncé, who’d spent a decade telling men to “put a ring on it!” released Lemonade, standing over the grave of her faith in pain-free love intoning: “ashes to ashes, dust to side chicks”. Using black and white film and vintage samples, Beyoncé had never sounded so much like Del Rey.

Del Rey also shifted her position. Aligning herself with the poetry of American identity – the Walt Whitman line about containing multitudes is her Twitter bio – she spoke out against a president who was shutting down the freedoms that had thrilled her. She dropped the flags from her artwork. As a musician who’d always incorporated rap rhythms and ideas into her dreamy soundscape, she hit out at Kanye West for his support of the Trump administration: “I can only assume you relate to his personality on some level,” she said. “If you think it’s alright to support someone who believes it’s OK to grab a woman by the pussy just because he’s famous-then you need an intervention as much as he does.”

Like a host of unexpected, self-invented artists before her – think Billie Holiday (Eleanora Fagan) or Bob Dylan (Robert Zimmerman) – Del Rey came out as a protest singer this month when she released “Looking for America” in response to mass shootings in Texas and Ohio. She sang her dream of a country “without the gun, where the flag can freely fly/ No bombs in the sky, only fireworks when you and I collide”. And she listed the places she no longer felt safe to go: the park, the drive-in movie.

I worried that, lyrically, there might be places she no longer felt safe to go in 2019 either. Would she lose the courage it took to express her vulnerability? The difficult truths about the darker side of her sexuality?

Well, there’s certainly less of that on Norman F***ing Rockwell! . But it’s honest and vulnerable in other ways. On the terrific closing track “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have – but I have it”, she continues to own her duality. “I’ve been tearing up town in my f***ing white gown/ Like a goddamn near sociopath/ Shaking my ass is the only thing that’s/ Got this black narcissist off my back/ She couldn’t care less, and I never cared more.”

Del Rey offers hope (Getty) (Getty Images) I sang along to that with pure elation on my long night drive. I was having a blast, even as I tortured myself about the emissions from our car contributing to the apocalypse. Del Rey knew how I felt. On “The Greatest” she croons: “LA is in flames, it’s getting hot/ Kanye West is blonde and gone/ ‘Life on Mars’ ain’t just a song/ Oh, the live stream’s almost on…” The self-destruction she’s always described is now on a planetary scale. Listening to her feels like watching it from space: terrifying and beautiful.

And just when you thought somebody like Del Rey might throw up her hands and suggest we try to get our kicks while we can, she offers hope. On the beautiful “Mariners Apartment Complex”, the woman who once eulogised the thrills of submission tells us we’ve got her wrong. “You took my sadness out of context/ At the Mariners Apartment Complex/ I ain’t no candle in the wind,” she says. “I’m the board, the lightning, the thunder… baby, I’m your man.” The song sees her holding out her hand to a lover, lost at sea. My own hand’s reaching back. High five, Lana. And thanks.

Norman F***ing Rockwell! is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies