Excess, watermelons and ‘kinky tackle’: How ‘Nobody Else’ brought down the curtain on Take That

There were bust-ups, breakdowns and, amid it all, arguably their finest album. Ed Power reflects on Take That's most tumultuous year

On a summer’s evening 25 years ago, Gary Barlow ripped off his vest, appeared to rub it against his armpits and threw the garment into a baying, broiling scrum of fans. Then he began to sing.

“Load up on guns and bring your friends,” the Take That frontman emoted to a heaving Manchester G-Mex Arena, his brown hair slicked with sweat. “It’s fun to lose and to pretend…” Around him, Mark Owen, Jason Orange and, in the Dave Grohl role of drummer supreme, Howard Donald knocked out a bleary approximation of the opening salvo of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. It was terrible, it was amazing, it was terrifying – all at once.

The world’s biggest boyband covering dearly departed grunge messiah Kurt Cobain was just the latest chapter in what was proving the most surreal year in the lifespan of Take That. This was a phase of their history strip-lit with excess, regret, watermelons, bad hair and questionable trousers. There were bust-ups, breakdowns and, amid it all, arguably their finest album.

Nobody Else was released a quarter of a century ago this month, on 8 May. Admittedly, it is unlikely to be mistaken for the second coming of Sgt Pepper (the cover of which it parodied) or a foreshadowing of OK Computer. And yet it represented a landmark for Take That and their audience.

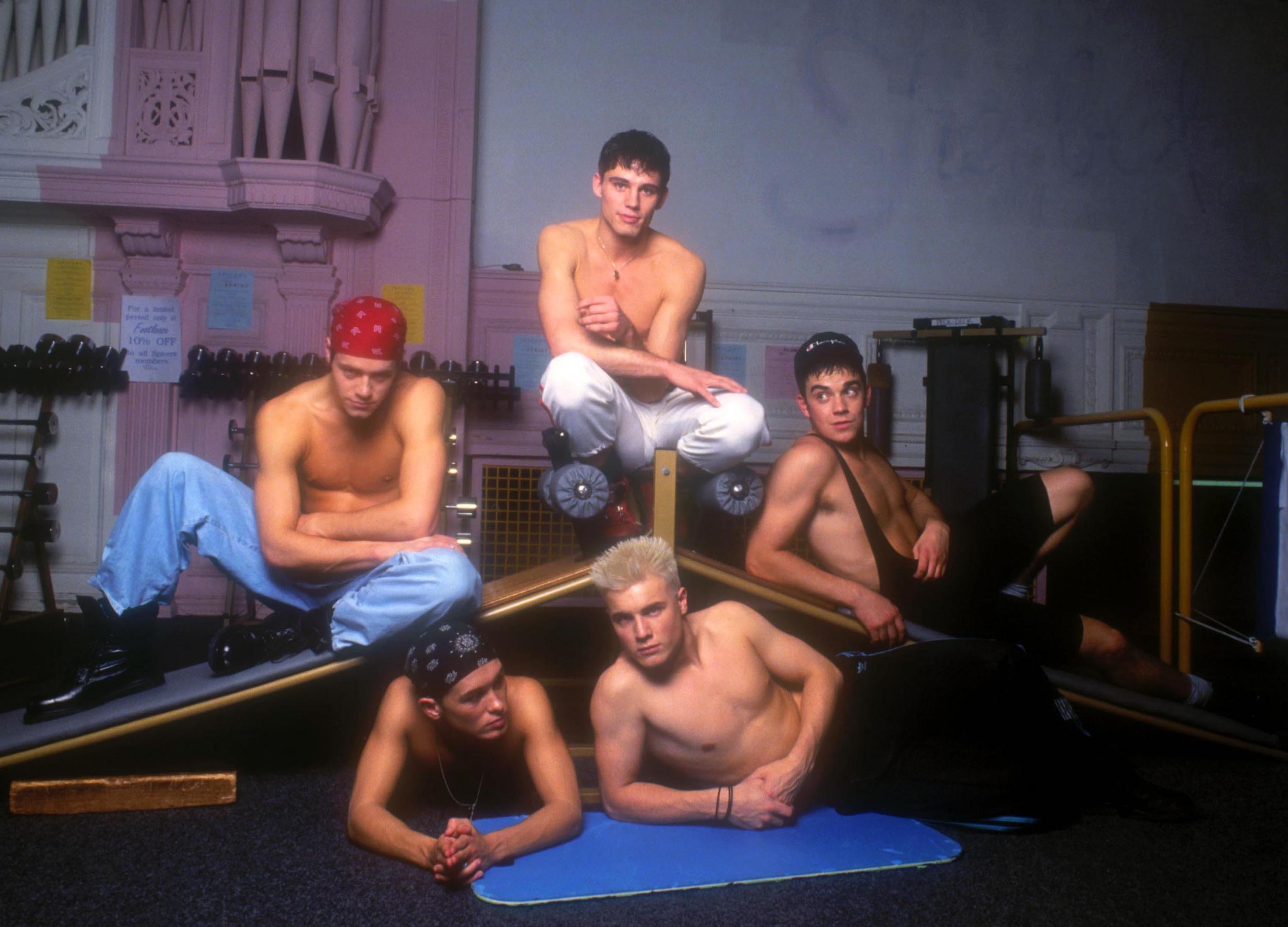

Up until then, they were regarded – even by some within the group – as the top 10’s original naughty boys: irreverent, often semi-naked and with an agreeable line in disposable pop. As formulas went, it was tremendously successful.

Take That were by a distance the biggest force in British pop, spawning imitators and rivals such as Boyzone, Westlife, 5ive and East 17. The era of Britpop was, even more so, the glory days of Take That. By 1995, they had sold upwards of four million records and clocked up a dozen hit singles.

Nobody Else, however, took them to the next level. Here was confirmation of Barlow – naff hair and duff Kurt Cobain impersonations notwithstanding – as a songwriter to be reckoned with. It contained their best song. “Back For Good” is an anthem so timeless even Noel Gallagher had to admit to being besotted with it. Sales-wise, the album went like proverbial hot cakes, moving six million units. And this was the closest Take That came to cracking America (not all that close, mind – it stalled at 69 on the Billboard Hot 100).

Yet, as is so often the case in pop, it was a bittersweet triumph. As was standard with Take That at that time, Robbie Williams, a former teenage bodypopper from Stoke-on-Trent, had found a way to make the release cycle all about himself.

A bug-eyed John Lennon to Barlow’s lounge-crooner McCartney, Williams left the group at the start of rehearsals for the summer tour, on 17 July. The news become a national talking point. “Why?” pined the 2 August edition of Smash Hits, which devoted five pages to a story of historic magnitude.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Did Robbie walk voluntarily or was he pushed? To this day, nobody can quite agree. Either way, neither side was all that devastated that he was out of the picture. Take That had long been divided into two camps: the hard-working Barlow, Owen, Orange and Donald v Party Boy Robbie. With his departure, a great weight was lifted from all involved.

There were obvious challenges. Just weeks before the Nobody Else tour, the now four-piece had to reconfigure their act, which was how the idea of doing “Teen Spirit” with Barlow on lead vocals came about. Yet, far from floundering, the Robbie-less Take That were ultimately leaner, meaner, more focused. And they were led by Barlow in his prime. Unlike its predecessor, 1993’s Mercury-nominated Everything Changes, Nobody Else didn’t feature any lead vocals from the charismatic Williams. Barlow instead wrote, arranged and sang on all 11 tracks, receiving a production credit for nine.

The bad news is that the tinkly weepies that were Barlow’s speciality were not especially fashionable – the rehabilitation of Elton John, for instance, was still years off. In the mid-Nineties, the Rocket Man was derided as a syrupy adjunct to Disney steamrollers such as The Lion King. More Seventies crock than “Crocodile Rock”. As Take That tried to expand their following beyond teenage girls, Barlow’s traditionalism posed challenges.

His reluctance to follow the trend for high-energy pop had led to tensions with manager Nigel Martin-Smith. Taking note of the popularity of New Kids on the Block in America, the Svengali had put together Take That in 1990 and overseen their dramatic rise. Going into the Nobody Else sessions, at Chris Blackwell’s Sarm West Studios in Ladbroke Grove in London (with further recording at Barlow’s mansion), he’d pushed Barlow harder than ever.

He wanted the singer to work with voguish producers such as David Morales and M People collaborators Brothers in Rhythm. The goal, as Martin-Smith understood it, was breaking America. Barlow, a former pub singer from Cheshire warbling at a piano, was never going to do that. Not on his own, at any rate. “Nigel was hustling me to write Usher-style bump and grind,” Barlow wrote in his 2018 memoir, A Better Me. “All I wanted was to write these power ballads.”

Barlow was becoming increasingly confident in his abilities and less inclined to listen to Martin-Smith. The success in 1993 of “Pray”, Take That’s first classic single, had made him less inclined to listen to his manager. Such was his frame of mind when he wrote “Back For Good”. As is frequently the way with pop classics, the song came to him quickly.

He had wanted to do something with just four chords. He worked out the piano melody and hummed the opening line. Later, he came up with the lyrics. They pushed against the sweetness of the music and brimmed with foreboding. Indeed, they almost seemed to foreshadow the drama about to jolt Take That. “I guess now it’s time for me to give up,” Barlow sings. “I feel it’s time…”

Elsewhere, Barlow was keen for Robbie Williams to sing on “Nobody Else”. In the early days, Williams’s powerhouse voice had come as a surprise to the Take That camp (he’d really just been hired for his dancing). Those pipes had been deployed on, among other hits, “Everything Changes But You”, the fourth single from Everything Changes.

Of course, that had been relatively early in the group’s history. Williams was still on what passed for his best behaviour. “From the time I realised I couldn’t get the sack, that’s when they lost me,” he would declare in the Simon Cowell-produced 2005 documentary Take That: On the Record. “‘I am now too powerful’. That was the time I went ‘fine, let’s do drugs’. “

Williams had been into acid and ecstasy prior to Take That. Yet, fearful of getting the boot from Martin-Smith, he’d initially kept his head down. By 1995, however, he was living on his own in a hotel in Manchester, downing a bottle of vodka a night.

The first casualty was his voice. By the time the got into the studio for Nobody Else, Williams’s bouncy croon had been ravaged. Barlow gave Williams 12 songs he felt might work for him as a lead vocal. Robbie demurred, saying that he wanted to pursue songwriting on his own. The truth was that he simply wasn’t up to it. “I abused my voice and paid the price.”

Alarm bells were clanging for his bandmates. These turned to full-on shrieking sirens as, several weeks after the release of Nobody Else, Robbie went to Glastonbury and partied with Oasis. In a figurative sense, he never really returned. “He came back and was absolutely wasted,” Mark Owen would recall in the On the Record doc.

“Something just snapped inside my head,” said Williams. “I’d gone… I’d physically and mentally gone.”

In the end, though, it wasn’t a lost weekend with Oasis or bottles of vodkas back at his that broke Take That. The tipping point was Williams nipping out for a cheeky McDonalds during preparation for the Nobody Else tour.

This was set to begin on 5 August at the G-Mex in Manchester before moving later that month to the 19,000 capacity Earl’s Court in London for 10 straight nights. Rehearsals were at glamorous Cheshire Territorial Army Barracks Stockport. And, as was often the case with Williams, he was struggling to knuckle down.

When he returned from his clandestine chip-run, he found his four bandmates waiting, arms folded. They wanted “a chat”. It quickly turned into a shouting match. “If you are going … go now so we can get on with it,” said Jason Orange, a one-time painter and decorator and the quiet one in the ranks, who’d never gelled with the extroverted Williams.

That’s exactly what Williams did. On his way out, mentally exhausted, massively hungover and stuffed with chips, he seized a watermelon from the fruit bowl and made a point of asking his now-former comrades if it was alright if he helped himself. He didn’t even like melon.

The rest of Take That were upset, especially as pictures later emerged of Williams partying in the south of France with George Michael. Clearly, he’d moved on. However, they didn’t regard his departure as an existential blow. A few years prior as they were on the up, Martin-Smith predicted Williams’s involvement would end exactly as it had. “He’ll just fly off,” the manager said. “And we won’t be able to stop him.”

Williams, for his part, had never felt any true camaraderie in Take That. Starting out with the group, he lived in constant terror of being sacked. By the time he had realised that was no longer possible, egos had taken over.

“There was a lead singer and we were, for all intents and purposes, backing dancers and it was a stepping stone for someone’s career, and we were viewed as such,” he told Chris Heath in his 2017 portrait of the artist, Reveal: Robbie Williams. “Obviously that’s going to rankle with me because I’ve got ambitions and dreams of my own that were sort of being usurped.”

Even more so than his bandmates, Barlow found it easy to accept Williams had left. The first time he had clapped eyes on Williams they were lining up to audition in 1990 at the La Cage wine bar on Bloom Street in Manchester (Williams was told he had made the cut the day he found out he’d failed all his GCSEs apart from English). It wasn’t as if they had come up together in pop’s school of hard knocks. They were colleagues, not brothers.

No, what bothered Barlow was the image problem he felt Take That continued to suffer. Early on, Martin-Smith had tried to break the band in gay clubs in the north of England, where they would cavort in S&M leathers.

Even after all their success, Barlow felt that there was still an expectation to play up to a pervy persona. This, rather than the departure of William, was what rang the death knell for Take That, who announced they were breaking up on 13 February 1996 (Williams’s 22nd birthday).

Raunchy dancing was part of their DNA from the outset. But as Barlow grew into his songwriting it became a distraction. “Pray”, for instance, was overshadowed by the soft-porn video, which featured copious lingering shots of Jason Orange’s greased-up torso.

That was fine in the UK, where audiences could juggle in their heads the idea of Take That both as a X-rated gyrators and purveyors of classic pop. In America, however, it simply didn’t fly. This was made bluntly clear by the president of their US label, Columbia Records mogul Clive Davis. “I don’t want this band on TV in America,” Barlow recalled Davis stating. “The way they look doesn’t match the record.”

“Sexuality was a big part of Nigel’s vision for the band, in a very homoerotic, adult way that Nigel was convinced was our trademark,” Barlow continued in his autobiography. “The dancers’ clothes were never sexy enough. Nigel loved all the Madonna Sex-era stuff, with her hitching naked… That’s Madonna. Not us.”

The crunch came as Davis flew in to watch Take That at Earl’s Court in August 1995. He’d seen the “Back For Good” video – the one with the rain and Robbie in a soaking fur coat – and at Earl’s Court expected four grown-up choirboys with superstar quiffs.

“He’s hearing ‘Back for Good’, going ‘this is a hit – I want this’” Barlow writes. “Then he sees us at Earl’s Court and he’s horrified by us in our devil horns, gyrating around to ‘Relight My Fire’ and Howard with his arse hanging out. He’s going, ‘Where’s “Back for Good” – where are the guys on stools, strumming guitars?’”

Davis’s disapproval was communicated to Barlow. The singer could only agree. He didn’t see a future that involved Howard Donald’s “arse hanging out” either. “It’s part of the reason why the band split up, that whole sex thing… Tour by tour, I felt less and less comfortable trussed up in all this kinky tackle.”

They would be gone within the year of Nobody Else. Beyond their immediate circle, the February 1996 announcement arrived from the blue (it was a surprise to Williams). A greatest hits album followed and a farewell tour that wrapped upon that April in Amsterdam.

Within a few years, it was Williams rather than Barlow who was the international superstar. Clive Davis’s attempt to turn the frontman into a hit machine in America would flop. His second solo LP, 1999’s Twelve Months, Eleven Days, stiffed at 35. It was such a disaster that his label, BMG, dropped him. That same year Williams had two mega hits with “Strong” and “She’s the One”. Life can be funny sometimes.

Yet the writing had arguably been on the wall regarding Barlow’s American ambitions as early as Nobody Else. Hoping to make Take That more palatable to the US, Meat Loaf and Sisters of Mercy producer Jim Steinman had been paid a reported six figures to work his magic. He duly remixed single “Never Forget”, featuring a rare lead vocal from Howard Donald. Steinman did so in Los Angeles, having never met Take That. It did little to raise their US profile.

Tail between his legs after the failure of Twelve Months, Eleven Days, Barlow would retreat to his manor house in Cheshire (featuring its own nightclub and six-acre lake). There, he did little beyond eating breakfast cereal, feeling sorry for himself and figuratively sticking his fingers in his ears whenever Robbie Williams and his global success came up.

There was a happy ending, though, with the group reforming in 2005. And yet Take That 2.0 – joined by Williams for 2010’s Progress LP and tour – were a very different proposition. The bondage kit and bare bums were out. Instead they wore suits, cultivated stubble and kept their rear-ends safely tucked away. Thus, the argument can be made that the original Take That – the dewy-eyed, perved-up pop idols of the mid-Nineties – had their final bittersweet hurrah with Nobody Else.

That album isn’t timeless. Much of the production screams “Nineties” the way David Beckham’s early Manchester United haircuts do. But as the soundtrack of a band on the brink, it is a fascinating time capsule. There is even the case that it is the pop equivalent of Let It Be or Hotel California – a record assembled by a group already falling apart.

“Things became too chaotic,” is how Jason Orange later epitomised the last days of Take That. “We were all getting too much money perhaps. The egos became too inflated.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies