The Big Question: What is being done to tackle illegal downloading, and will it succeed?

Why are we asking this now?

After years of wrangling, the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) – the body that represents the UK's major record labels – has got agreement from the biggest Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to go after people whose taste for downloading free music is arguably the biggest threat the music industry has ever faced. Yesterday it was announced that the government had brokered a deal between the two sides that agrees measures to be taken to try to control the problem.

What does the deal say?

The agreement will see six ISPs writing to illegal file-sharers to warn them that their actions have been noted – sending a thousand letters a week between them. No settlement has been reached on exactly what actions should be taken against persistent offenders, but one measure floated is to slow drastically or remove the internet connections of those who ignore three warnings. It seems that life is about to get a lot tougher for teenage music lovers.

Won't the industry go after the big offenders?

Not according to Geoff Taylor, the Chief Executive of the BPI. "There is not an acceptable level of file-sharing," he says. "Musicians need to be paid like everyone else." The BPI insists publicly that it would be a strategic mistake to only focus on the "uploaders", people who make their music available, since part of the point is to make everyone think twice about doing it. In practice, very heavy file-sharers will probably be the most likely to get caught.

What is file-sharing?

It's the modern-day version of recording a friend's album on to a tape. Services like Limewire allow their millions of users to make their own music collections available in a vast searchable database that anyone can access. That means that you can download your very own digital copy of more or less any song you can think of in a couple of clicks. Any kind of file can be transferred in this way, and the problem applies to films and TV shows as well.

So why is it sucha big deal?

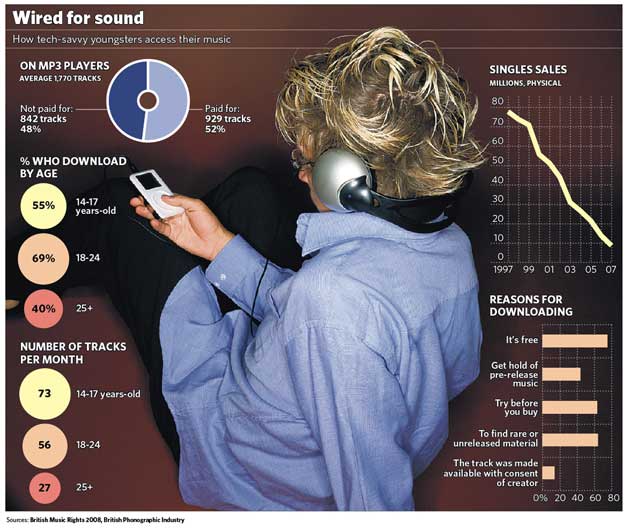

Ever since the internet became fast enough to download large files like MP3s, the sale of music on physical formats has been in steep decline. The advent of broadband and ubiquitous high-speed services like Limewire have only exacerbated things. In 1997, 78m singles were sold in the UK; last year, it was just 8.6m. Now users download an average of 63 free tracks per month. Paid services like iTunes have lessened the blow somewhat, and album sales aren't haemorrhaging quite so badly, but the impact on the industry has nevertheless been profound.

Why has the problem taken so long to sort out?

Initially, the record labels reacted sluggishly. When they did wake up to the scale of the problem they found that without the help of the ISPs, they were more or less powerless to act. It's the ISPs that have the personal details associated with the accounts doing the downloading, and they have always been reluctant to be proactive – arguing that it's not their job to police users.

They probably also calculate that any service provider that takes a unilateral stance will quickly be deserted by its biggest customers, in favour of rivals with a more liberal regime. As recently as April, Charles Dunstone, the Chief Executive of Carphone Warehouse, one of the biggest ISPs, ridiculed the BPI's efforts, saying: "They're not just shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted – the horse has left town, got married, and started a family." But now Dunstone is on board.

What's changed?

The Government got involved, making it clear that legislation would be inevitable if the service providers didn't take action on their own. Thus motivated, Dunstone and co. changed their stance, albeit reluctantly – reasoning that collective action would make the consequences less commercially prohibitive. "We believe it is in [our customers'] interests to warn them that they are being accused of wrongdoing," Dunstone said yesterday. "We will not divulge a customer's details or disconnect them on the say so of the content industry."

What impact will the proposed changes have?

At the moment, the BPI and the ISPs are saying different things about what the consequences of the letters will be. Dunstone's remarks make clear that companies like his are still loathe to hand in their customers, and they carefully refer to the letters as "informative"; on the other hand, the assumption on the part of the BPI is that eventually persistent offenders will face the removal of their internet connection.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

But even the letters themselves will be enough to have some impact: a recent study by Entertainment Media Research suggested that 70 per cent of illegal downloaders would be sufficiently intimidated by a stern letter to desist. The percentage is even higher amongst the teenagers responsible for the lion's share of the problem – in particular if the letter was addressed to their bill-paying parents.

What happens if none of this works?

Then the government will legislate. Although consumer rights advocates see the threat of removing the internet access of downloaders as a disproportionate response – arguing that the internet is a crucial means of contacting the world these days, and should not be cut off for indulging in a practice that is now socially acceptable to many people – that is the most likely action.

So is the music industry doomed?

Almost certainly not. Single sales may have dropped, but 28 million more albums were sold last year than a decade ago, including digital sales; and live performances, which account for more than half of the industry's profits, are unaffected by downloads – and may even be boosted by the opportunity they offer for young people on tight budgets to sample the music they might like to hear at a concert.

Even online, the record labels will probably be able to boost their profits on the back of another condition of the agreement, which calls for the ISPs to establish their own legal download services. One established by Sky last week, on the same subscription model as the "licence fee" suggestion, probably points the way to the future of legal downloading. There's no need to pity the industry bosses just yet.

Should you feel guilty about downloading music illegally?

Yes...

* You wouldn't walk into an HMV store and steal a load of CDs, so why is it ok to do so online?

* Musicians aren't all millionaires. If you like their work enough to want to keep it you should reward them for it

* Some of the music industry's profits are ploughed back in to helping you find your next favourite band

No...

* People download things they wouldn't bother with if they had to pay – and then buy more albums if they like what they hear

* If you want to listen to an obscure bootleg of a concert that isn't available to buy anywhere, why shouldn't you?

* The record industry is making handsome profits anyway, and ripped everyone off before downloading was an option

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies