Radio: Who needs pictures in a digital world? The medium is still remarkably resilient

We live in a digital world, yet radio is proving remarkably resilient, and more relevant than ever

Well, it turns out that video didn’t kill the radio star after all. As much as television still enchants with chimera for the eye, increasing numbers of us are choosing to close our eyes and listen, too. More and more people are tuning into the radio: figures are steadily rising, year on year.

Somehow, even though this is a generation that has always had radio, its climbing popularity feels counterintuitive: we exist in an age in which new technology is fiercely competing, and consistently evolving, to allow individuals to be as powerful in their personal listening habits as possible. And yet, despite iPods and digital downloads, access to music and programming, despite independent podcasts from all over the world, playlists and “genius” versions of playlists, and gigabytes worth of information straight from the internet to our ear, the most recent figures from RAJAR/Ipsos Mori/RSMB show that 91 per cent of the UK population is tuning in (or searching, tapping in and scrolling down) to a radio station each week. That translates as 48.38 million people; 36.22 million of whom are listening to the BBC – a corporation founded in 1922, in an era when radio itself was still considered somewhat magical.

Or perhaps it’s not counterintuitive at all. We have had radio for so long that it has implanted itself in our consciousness. It is a medium that requires our imagination to be active in the listening, and so has a different and inherent lineage for each listener. We can’t see the interviewees, the story-tellers or the musicians. We have to imagine them, listen to what they’re saying first, rather than instantly forming an impression of them because of their haircut or outfit. Radio is more nebulous than television, but perhaps more far-reaching because of it.

In the same way, familiar voices, less quick to age and change than faces, are triggers for memories, soundtracks to periods of life. Before telling me a story, my father used to say, “Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin” – a direct quote from Listen With Mother, the BBC radio programme that he listened to every day as a young child in the early 1960s. The radio show Children’s Favourites came from the same era, too. It began with the catchphrase “Hello children… everywhere”, and played tunes such as “Nellie the Elephant” and “The Runaway Train”. My parents nostalgically played me the cassettes from the radio show when I was little, and now I listen to the same songs with my own small children, from what they call the “puter” (iTunes). It’s a kind of heritage, a line through.

And just like voting habits, many families have an allegiance to particular stations – sport, news, music – that become a subliminal imprint. My mother, from the south of Ireland but living in the north, would never be without RTE, the national radio station of her birthplace. When she comes to visit me in London, she listens online, and suddenly my kitchen hovers between worlds: global news is heard from a different slant, and hearing that traffic is bad on a little road in Carrigaline, County Cork, calls up half-recollections of this, one of the soundtracks to my existence. (I can still remember one of the adverts from that station off by heart, said in a faux-American, but clearly Irish, accent: “Come to Barry’s Hotel. You’ll meet all the stars there – there’s Declan Nerney, and Louise Marcy, and Big Tom, too. Thursday night is nurses’ night!”)

Cerys Matthews, whose Sunday morning programme is the biggest single show on BBC’s digital station 6 Music, is a passionate advocate of how radio can weave into the day-to-day. “I love that you can have radio to enhance your life,” Matthews says, from a crackling telephone, as she drives to Wales. “People are listening while they’re cooking, painting, doing graphic design – television [can be] intrusive, but radio is intimate and all-giving: your life isn’t on hold while it sucks your attention.”

Throughout her show, she gets tweets from listeners in Nairobi and Ukraine, Brazil and Addis Ababa – and, in the UK, people are constantly getting in touch: great-grandmothers, parents of newborns, fans in sheltered accommodation, and students. It’s a mismatch of demographic that doesn’t fit into any neat statistic, yet all strangely united by what they’re hearing. This is how radio really works alongside the digital revolution. And this ability is, she thinks, one of its strengths. “It feels fresh,” she says, and more so than television, with its capacity to respond to whim. “If I hear or read something interesting, I can put it in to the show hours later.” Lack of visuals, she laughs, “circumvents all those horrible dreary things – make-up and stylists… [television has] become a bit like the Seventies again, all too stylised and marketed.”

It’s the opposite of this – the creativity of the radio format – that really drives her. “The freedom we’ve got now to find and source music on the internet means that people can digest things differently,” she says, referencing the fact that her adventurous weekly show, which bears good comparison to Bob Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour, journeys through soundscapes from multiple genres and eras that are impossible, as a listener, to predict. “I think we can cope with it – we’re intelligent enough… the ear never tires.” Matthews doesn’t work off a certified station playlist: she picks all the songs and the guests herself. Her listening figures have been increasing since she started in 2008, and the station recently extended her two-hour show by an hour.

Bob Shennan is a fan, which is a good thing since he’s Matthews’s boss: and, as the controller of Radio 2, Radio 6 Music and the Asian Network, he is more than cognisant of the listening figures. “We all think about it a lot,” he says. “There are so many different ways that people can access content… the challenge is to keep them listening.” Shennan was given his role in 2008, just as 6 Music and the Asian Network were under threat of being slashed from the BBC portfolio. A huge groundswell of public protest saved 6 Music – it is now the UK’s leading digital station, with 1.96 million listeners – and he was charged with streamlining the Asian Network. Listenership for that station now sits at 668,000 and rising, and a success as far as Shennan is concerned, working at 45 per cent of its original budget. It also now has a remit to deliver what he calls “impact journalism” by breaking stories that transfer to other news outlets. So while non-Asians may not specifically listen to the station, they will have heard significant stories that originated from there: British Muslims who risked their lives to deliver aid to Syria, or how Asian footballers are represented in the professional game. “Why is radio still so magnetic?” he asks. “It is very personal… in the way television finds it difficult to be.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Maybe it is that in a world where choice can be cataclysmic, we really like someone to curate it all for us. And if we find a station that appeals, it feels in our internal landscape like a home. Having to broadcast from a boat just to play certain types of music seems pretty alien to our download culture now – not least when figures this week show digital music revenues from services such as Spotify and Deezer account for half of the UK music industry’s income. But the ethos of pirate radio – no need to bow to the mainstream playlist – hasn’t disappeared. It has just evolved.

Thanks to digital streaming, enterprises such as the Boiler Room, which started off as a club in east London, have been born. Since its first live streaming of a DJ set in 2010, the Boiler Room is now a major broadcaster of underground music. Organising exclusive DJ performances in small venues that are then streamed live to listeners around the world (who are vocal on social networks throughout), the Boiler Room mixes have gone global. On Twitter, its profile reads “The worlds [sic] leading underground music show”, which seems apt: it now has offices in New York, Berlin and Los Angeles, is attracting big names and has a steadily rising Twitter following, which stands at 154,000. It’s a tribe, a community.

The sense of community in a radio station holds true across the spectrum. In 2008, Radio 4’s Today programme interviewed a British businessman over the telephone from Mumbai, just after he had survived the shootings by members of Lashkar-e-Taiba. He broke down in tears halfway through: the sound of the interviewer’s voice, he said, was reassuring; back in the UK, he listened to the Today programme every morning. The voices were home to him, ever-present, in control. Maybe that feeling is why it seems funny when ordinarily composed presenters make mistakes. The notorious slip of the tongue that both James Naughtie and Andrew Marr made on air on Radio 4 in December 2010 – when introducing Jeremy Hunt, the culture secretary, as something rather different – sparked great merriment and made headlines itself. And the recording of Today’s ordinarily super-composed Charlotte Green collapsing into giggles as she tried to recover from presenting the earliest recording of the human voice (which sounded uncannily like a bee), has been listened to on YouTube 191,654 times.

In this way, radio seems to be moving in harmony with the constantly evolving technology swirling around it. Last week, Radio 4’s Mishal Husain presented a feature about the special effects used for the (now award-winning) film Gravity, and conducted a very intelligible discussion about how the space suits you see Sandra Bullock and George Clooney wearing on screen don’t actually exist. It all seemed perfectly reasonable until Husain tweeted a link afterwards to an animation, a “pre-visualisation” that the film-makers used, to imagine what the final result would be. She explained that she had done this “to back up our attempts to talk about visual effects on the radio”. This is where radio really chimes with the digital age. It has the immeasurable reach of millions of imaginations – and it has backup. Husain has 130,000 followers on Twitter: suddenly, what radio stations call their “reach” is magnified.

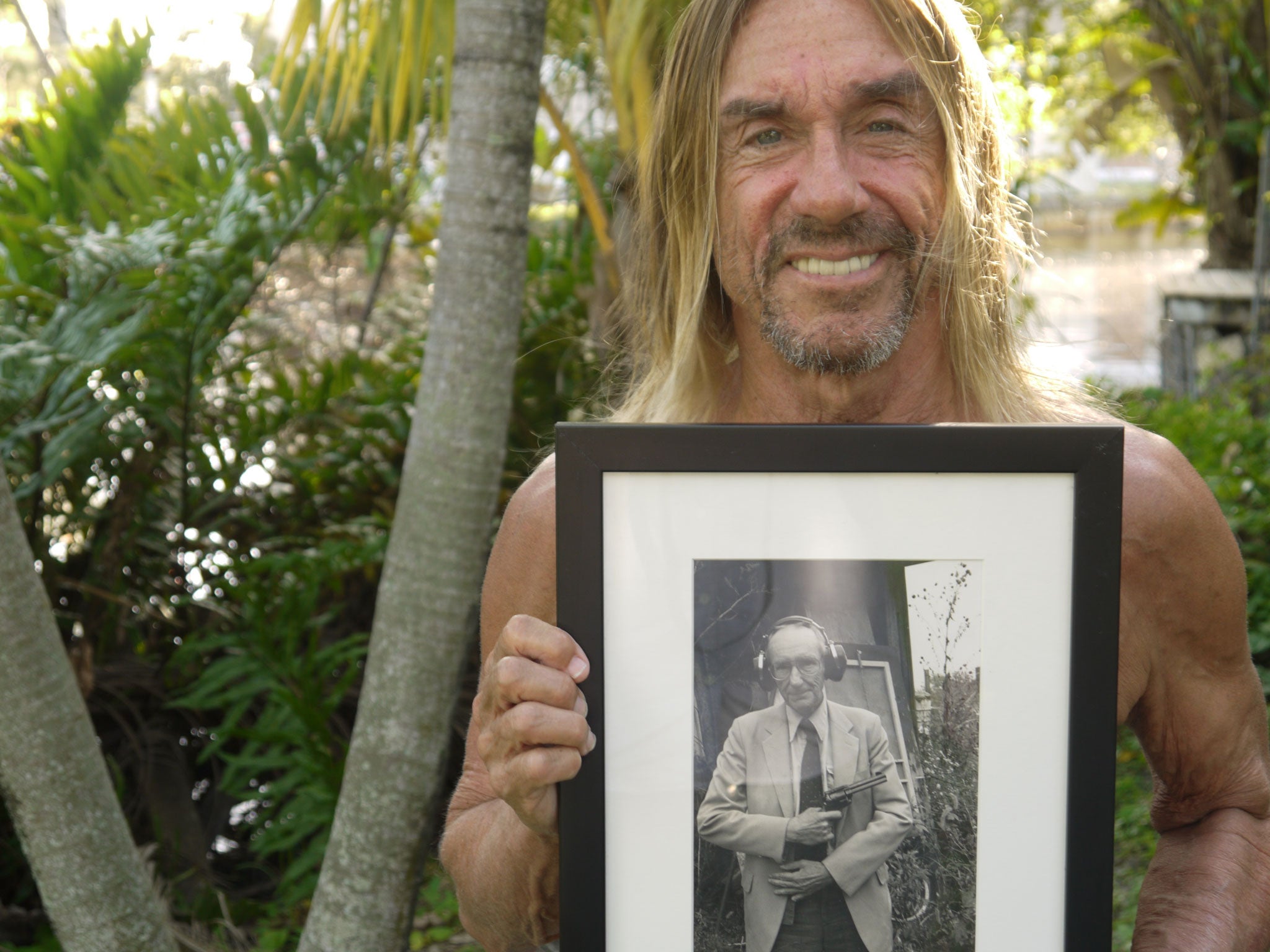

“Radio has rediscovered its old ‘fleet of foot’ values,” agrees David Prest, the managing director of Whistledown, an independent radio production company which is also one of the largest suppliers to the BBC. “There’s an appreciation from programme makers that we have to be responding in the here and now. People expect to hear the news first on radio, and then expect better quality discussion and analysis, and more quickly”. Prest, as recipient of the Radio Academy’s Indie of the Year in 2012, is very much alive to how radio is evolving. “An on-air listen can be turned into a viral download overnight. It gives programmes an afterlife, a global audience, and is rapidly changing the way people consume,” he says. He made the recent Radio 4 Iggy Pop documentary on William Burroughs, and feels that radio is becoming increasingly edgy, commissioning programmes that before would have been considered “dangerous”. (Prest also made the Tony Harrison “V” poem – filled with taboo words, no Freudian slips needed – for the BBC, which is as clear an example of his point as any.)

Meanwhile, over on Radio 1, the Twitter feed is followed by 1.67 million people, who receive constant updates about song choices, competitions, upcoming guests. And the listeners, mostly teens and students who are tooled up when it comes to social media – tweet back. A conversation is happening in the ether, simultaneous to whatever is happening in the sound waves. The wireless really has gone wireless.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments