Forever Young: How Rock'n'Roll Grew Up, BBC4<br/>Rev, BBC2

They were hoping to live fast and die young, but at least they can cash in on the golden age of rock'n'roll

Don't mention the "O" word. As the array of rock'n'roll relics lined up to give great quote in BBC4's Forever Young, one word remained strangely absent from their lips. They spoke of dignity. They spoke of maturity. They spoke of growing into their own material. They spoke of survival.

Motörhead's Lemmy mentioned it once, but he got away with it because, talking about his own ability to live fast and live on, he described himself, at 64, as "almost old".

Yet age was at the very heart of this documentary, which set out to show how rock'n'roll – that supposedly passing fad of the late 1950s and early 1960s – had, largely thanks to the Beatles, outgrown its own roots to morph from a rites-of-passage act of rebellion to the defining cultural phenomenon of the late 20th century.

But before we get all "Pseuds Corner", there was one other subject that no one – again apart from Lemmy, who admitted that he dyes his black – seemed prepared to talk about at any length: and that was the importance of retaining a full head of hair. Because what Robert Wyatt, John Paul Jones, Peter Noone, Bruce Welch, Rick Wakeman and Joe Brown all had in common was an uncommonly good thatch. And, given that nearly seven in 10 men will suffer male pattern baldness by the time they are 60, this lot bucked the stats to such a degree that either there is a discreet transplanter somewhere making a small fortune, or there is some undiscovered connection between sex, drugs, rock'n'roll and free-flowing locks. (Forever Young's one follically challenged participant, Richard Thompson, is never seen without a beret.)

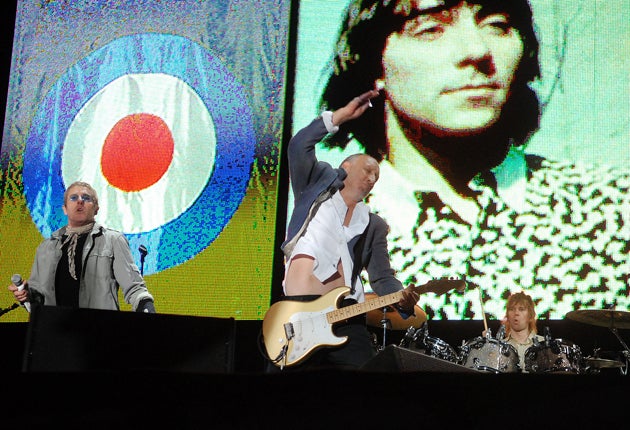

Forever Young restrained itself for precisely three minutes before it gave in and mentioned those unforgettable words in the Who's "My Generation". Were it possible to go back in time, perhaps Pete Townshend would force his 20-year-old self to amend the lyric to "I hope I die before I go bald", but the line stands and he has had to live with that decision every time he has plugged in his Stratocaster since.

"What happens," narrator Cherie Lunghi asked as her opening gambit, "when rock'n'roll's youthful rebelliousness is delivered wrapped in wrinkles?" Mick Jagger, interviewed in the aftermath of punk rock for a Rolling Stones "comeback" tour in 1981, told us, "I think I could do this kind of physical show for about another five years," before Rosie Boycott came on to point out the strange disconnect between Jagger's body and face as he, at 66, still slinks his hips along to "Let's Spend the Night Together".

Iggy Pop, a strange person to ask about such matters, not because he doesn't have the requisite wrinkles but because the programme had promised to explore "Britain's rock'n'roll generation", gracefully admitted that though he can still perform his youthful material, he doesn't have the "animal energy to write a great rock'n'roll song any more" before complaining about aching knees. Alison Moyet went one step further, saying that while she wrote her best songs in her youth, the passing years have taught her how to deliver that material without resorting to silly dance movements. And surely, if the programme-makers could buck the Brit law for Iggy, Deborah Harry (65) would have been a more relevant and "rock'n'roll" exhibit than Moyet (49).

The dignity side of things was mostly left to Rick Wakeman – who pointed out that stars of his vintage were, these days, familiar with the sight of three generations of the same family enjoying "legacy" rock shows together – and Robert Wyatt, who touchingly confessed: "I had to live this long to get every third or fourth song on every third or fourth record I made spot-on." Conclusion? What age shall not wither, it can – as Wyatt's eclectic and entirely age-appropriate oeuvre demonstrates – invest with infinite variety.

Which is not a Shakespeare quote you can apply to TV vicars. As the lovably hapless Tom Hollander shone his way though the comedic murk of Rev, it was hard to escape the feeling that this gentle sitcom was merely The Vicar of Dibley in reverse. Where that show had Dawn French playing an inner-city cleric transposed to a country setting, this new series saw a rural reverend trying to make the best of his east London posting.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Aimed, perhaps, at those who loved Dibley but found Father Ted too sweary, Hollander had the good grace to remove his dog collar before uttering the "F" word and the show, for all its try-hard 21st-century references and excellent supporting cast, came across as old-fashioned as Derek Nimmo's All Gas and Gaiters. A programme, it must be noted, that hit screens in the same year that John Lennon declared the Beatles "more popular than Jesus".

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies