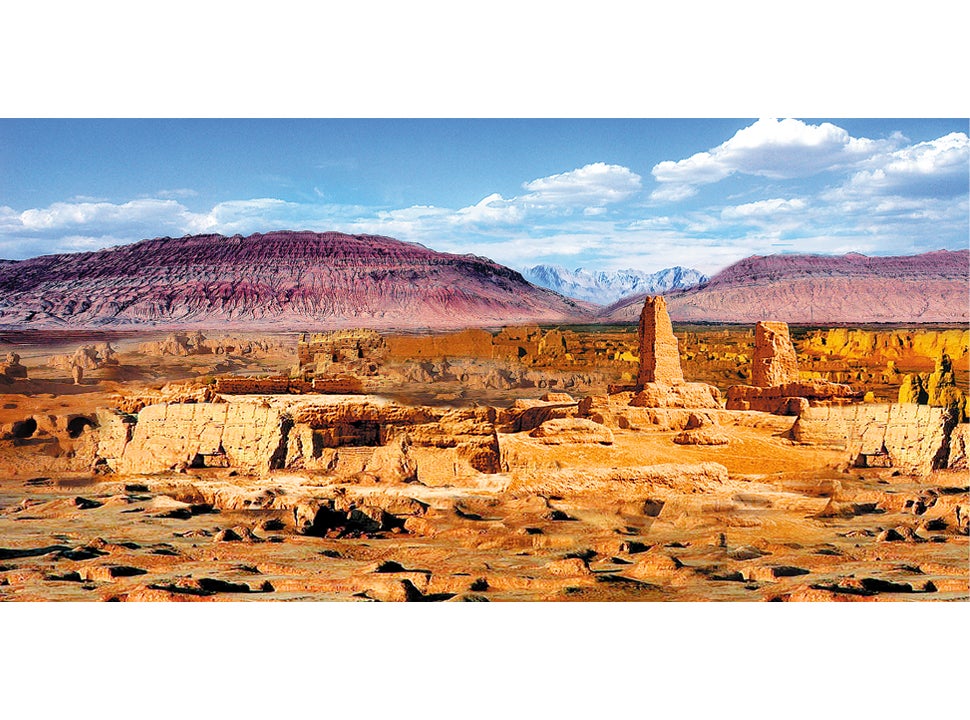

Mountain of relics

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY CHINA DAILY, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

A land of beliefs, opulence and great expectations, Xiyu (meaning “western regions”) has charmed rulers, merchants, poets and pilgrims alike throughout ancient history.

Mainly referring to the present-day Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region and parts of Central Asia, Xiyu was a string of oasis cities that dotted the Silk Road like pearls, stretching westward along the Tianshan Mountains. Bathed in multiculturalism and prosperity, they tell a millennia-long saga, the splendour and relevance of which have survived the sands of time.

These ancient cities may have fallen into ruins, but thanks to the diligence of archaeologists and descriptions in documentation, they have become concrete and stunning evidence that marks the peak of the Eurasian trade route network.

Since 2016, Guo Wu, a researcher with the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, has focused on the Beiting ruins, or Beshbaliq, the largest and best-preserved ancient city by the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains. Located in today’s Jimsar county in Xinjiang, the ruins have a core area of more than 370 acres.

In 2014, the Beiting ruins gained UNESCO World Heritage status by virtue of being part of “Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor”.

“The city thrived on an artery of the Silk Road’s northern arm,” Guo says. “Smooth trade in Xiyu depended on this place.”

Guo’s team has unveiled the layout of the city, including its road network, waterways and temples. Unearthed coins from the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties speak volumes for its booming business while tile decorations indicate social status and influence from Persia to Central Asia.

“The city was constructed uninterruptedly for 150 years under the Tang Dynasty. Small-scale adjustments in layout happened in the periods that followed. The city played a pivotal role until the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368),” Guo says.

In 702, Tang empress Wu Zetian ordered the setting up of the Beiting Protectorate there to govern the north of Tianshan. In the following centuries, it saw many dynasties come and go. Nonetheless, from Tubo and Qocho regimes to Khitans and Mongols, ambitions to uphold cultural exchange and ensure good business along the Silk Road were shared.

For instance, although Buddhism was widely in practice under the Qocho regime, Guo’s team unearthed a Christian relic – the cross – near the ruins of a Buddhist temple.

“The urban system centring on the Beiting ruins demonstrates inclusiveness, mutual learning and co-operation. They help us understand how a shared community of a Chinese nation was formed,” Guo says.

In the first century BC, following the orders of a Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) emperor, tens of thousands of soldiers left their homes in present-day Gansu province and moved further west to settle down in today’s Turpan by the southern slopes of Tianshan. They defended the frontier area and turned farmers in their spare time.

This settlement of soldiers grew to become a key point on the Silk Road and witnessed communication among various ethnic groups for almost 1,500 years. It is referred to as the Gaochang (Qocho) city ruins today.

Chen Aifeng, deputy director of Academia Turfanica, a Turpan-based research institute focusing on regional heritage, sees the city as a rare demonstration of glory of the Tang Dynasty, the pinnacle of Chinese imperial years, and its great ambition to connect with the rest of the world.

Mimicking the layout of Chang’an (present-day Xi’an, Shaanxi province), the capital of Tang, Gaochang’s walls, gates, temples and even marketplaces can easily help with reminiscences about the golden days.

“The ancient Silk Road was not really one ‘express route’ via which people covered thousands of miles at one go, like taking a long-haul direct flight from China to Europe,” Chen says.

“Merchants travelled for relatively short distances every time to do business. Gaochang thus became an intersection where silk, spices and other products from Central China and West Asia were traded, and where people also exchanged ideas.”

Like Beiting, the Gaochang ruins are also included in the World Heritage Site list as segments of the Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor.

Mao Weihua contributed to this story

Previously published on Chinadaily.com.cn

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.