Treaty offers world's last chance to save great apes

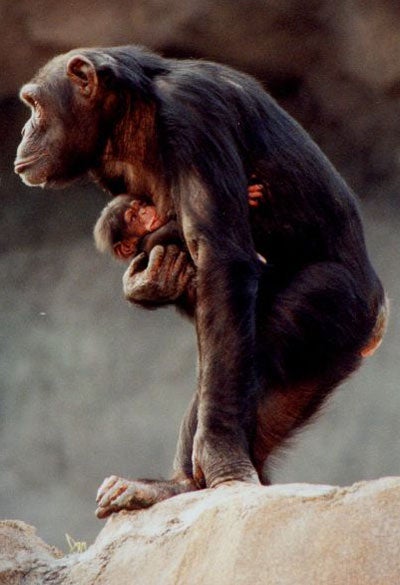

They are man's closest cousins and they are staring into the abyss. But in one of the most important environmental treaties, hope has been offered to stop the headlong slide towards extinction of humankind's nearest relatives, the great apes.

The agreement signed in Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, is on a par with the 1982 whaling moratorium and the 1997 Kyoto protocol on climate change. It offers a real chance to halt the remorseless jungle slaughter of gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos [pygmy chimpanzees] and orang-utans, which on current trends is likely to kill them all off within a generation.

If it succeeds - a big if - it will be the most significant move yet to counter the greatest environmental problem facing the world after global warming, the mass extinction of living species. Increasingly, the great apes are being seen as the flagship example of species that have become endangered. Last year, the African conservationist Richard Leakey said their image should replace that of the giant panda as the international icon of threatened wildlife.

The agreement in Kinshasa between the nations where the animals occur in the wild, the "range states", and a group of rich donor countries, led by Britain, publicly recognises, for the first time at the international diplomatic level, the unique cultural, ecological and indeed economic importance of the four great ape species, which share up to 98.5 per cent of our DNA.

It commits its signatories to a comprehensive global strategy to save them, which involves setting up much new legal protection and protection in the field, and widely clamping down on the illegal hunting, logging and other practices which are destroying their habitats and their populations.

Furthermore, it sets two ambitious targets: the first of significantly slowing the loss of great apes and their forest habitats by 2010, and the second of securing the future in the wild of all species and subspecies by 2015.

These are enormous tasks. At present the gorillas, chimpanzees and bonobos of Africa, and the orang-utans of Asia, are under merciless assault from deforestation, war, illegal logging and mining, the captive-animal trade, hunting (they are increasingly killed for food in some parts of Africa and sold as "bushmeat") and now from emerging diseases such as the Ebola virus.

The 23 range states which contain them, from Angola to Uganda, are among the poorest in the world, characterised by extreme poverty, violent conflict and soaring demand for the extraction of natural resources. Sixteen of them have a per-capita annual income of less than $800 (£430). Although in all of these countries the great apes are protected by law, wildlife protection and wildlife law enforcement tend in the nature of things to take a low priority.

The result is that ape numbers are tumbling almost everywhere. Ten days ago the firstWorld Atlas of The Great Apes was published in London and gave a graphic and alarming picture of rapidly shrinking ranges and increasingly isolated populations.

As few as 350,000 of all the great apes, which once numbered in their millions, may now exist in the wild, and populations of some sub-species are already down to a few hundred. Some conservationists such as the chimpanzee specialist Jane Goodall believe they may be extinct in the wild outside protected areas in the next two decades.

Certainly, if current trends continue, the specialists who compiled the Atlas believe that, over the next 25 years, 90 per cent of the gorilla range will suffer medium to high impacts from human development, as will 92 per cent of the chimpanzee range, 96 per cent of the bonobo range, and no less than 99 per cent of the orang-utan range.

The treaty signed at the weekend is the product of four years' work by the Great Apes Survival Project (Grasp), a partnership of the United Nations Environment Programme (Unep) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco), which has brought together conservation scientists, pressure groups, academia, the private sector and local communities.

Grasp has managed to convince virtually all the range states bar one Malaysia that saving the great apes is very much in their interests, by stressing that ape populations can bring enormous economic benefits to poor communities through eco-tourism. Ten years ago, for example, before the recent civil war in the DRC broke out, Virunga National Park, home of the famous mountain gorillas, was generating $10m a year.

The new agreement places ape conservation squarely in the context of the range states' strategies for poverty reduction and for developing sustainable livelihoods.

Grasp has also convinced rich Western donor countries that the poorest nations in the world cannot be expected to pay entirely out of their own pockets for saving the great apes. Britain has taken the lead, providing the first substantial donation to the Grasp budget in 2002 and helping to fund the week-long meeting in Kinshasa which culminated in the agreement.

It has been signed so far by a total of 23 range states and donor countries, including Britain, and remains open for further signatures (all the African range states, and more donor nations, are expected to sign).

It marks a hugely significant moment, said Ian Redmond, the British biologist who is Grasp's chief consultant. "The international community has belatedly recognised that the future of the great apes is the responsibility of all humanity, and not just the countries in which they live, which are among the poorest in the world," he said.

Conservationists were jubilant at the weekend at the successful signing of the accord, and in particular at the lack of dissent in the negotiations which led up to it. It led to optimism about the greatest remaining worry can the desperately poor African range states deliver what they have signed up to?

"I think it's achievable," said Jim Knight, Britain's Environment minister, who signed the treaty on behalf of the United Kingdom at the weekend. "I wouldn't have signed it if I didn't think that. We're proud of the Kinshasa agreement. It means that our closest relatives in the animal kingdom now have a chance of a future."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies