Raiders of the lost crafts

This week the nation’s capital has been celebrating the bright new stars of contemporary design. But as London Design Week draws to a close, Amalia Illgner looks to Britain’s heritage crafts and discovers, while we’ve been busy looking to the new, many traditional skills risk becoming extinct

“Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of fire” – Gustav Mahler

The pumpkin soup is saffron orange with swirls of cream, cinnamon and rock salt. When you cup the bowl, the warmth transmits straight to your heart. It tastes like a song. Wooden spoon grazes a wooden bowl. Where ceramic magnifies heat and cold, wood is somehow kind. It’s an invitation from nature to eat at her table. For roughly one thousand years this is how we ate. We had wooden bowls called “porringers”, wooden plates, wooden dishes, wooden spoons. The bowls, made by hand, were fashioned using foot-powered pole lathes. The maker would saw a five-inch thick wooden disc, cut a central groove, attach it to a rod that served as an axle, and then a foot-powered floor pedal would compel the disc to turn. As it turned, the maker would hold a hooked metal carving tool which hollowed out the bowl. This is called woodturning. And every village had a turnery. Think of all your friends called “Turner”. This is how their ancestors spent their time.

George Lailey was the last pole lathe bowl turner in Britain when he died in 1958, with no apprentice. His father had been a woodturner, so had his grandfather. We know that all over the country there are George Laileys practicing different crafts, who will retire or die without apprentices. We know that in their hands lie hundreds – often thousands – of years of knowledge. We know that these skills are part of our living history, helping us to understand how we got to where we are today. But what we don’t know is which skills are most in danger, where those makers are, and how they can best be supported. There’s no “endangered species” list for heritage crafts. At least not yet.

* * *

Of the 65 million people living in England today, it is estimated that 30,000 make a living from heritage crafts. To put this into context, you are four times more likely to meet someone whose stated religion is “Jedi Knight” than a professional heritage craftsperson. Right now, nobody can be certain of the precise numbers of makers for each craft, but in 2004 a report was published that gave some rough estimates such as: over one thousand dry stone wallers, between 100-200 chestnut fencers and four people who can still make hay rakes. Anecdotal evidence points to just one traditional clog maker, one scissor maker and one person who can still weave oak spale baskets, used in the Lake District for potato harvesting.

When Trevor Ablett, the last self-employed little mester making every day working pocket knives, died last October, aged 73 with no apprentice, his unique skills were thought to have died with him. But this May saw the announcement of the Radcliffe Redlist, which will document, for the first time, the state of the nation’s heritage crafts and formally identify the crafts at risk of becoming extinct. It will be released at the end of the year and will give makers a platform to articulate the type of support they need, so that perhaps the George Laileys of their crafts might find apprentices in their lifetimes.

Greta Bertram, the secretary of the Heritage Crafts Association, who is leading the Redlist research believes that the list will become an advocacy tool, and help connect makers with supporting organisations, along with documenting each craft’s historic significance. Carole Milner, the Heritage Crafts advisor to one of Britain’s oldest charities the Radcliffe Trust, which is funding the Redlist, says the project is vital as it taking a “strategic approach” to the issue of crafts at risk. “Of course”, she says, “there’s been lots of anecdotal evidence, but there’s never been a move to formalise the information and turn it into something that can be analysed and evaluated”. Milner says that from a funder’s perspective, the list will be vital as they get “dozens of applications every month” detailing the urgent needs of different crafts. “The list will help us have a better informed discussion about where to put funds – we can’t help everyone, so our attention will be on those crafts which have an obvious future, market potential or applications we believe are most worthy of preserving. ”

So, what was George Lailey’s ability to turn a wooden bowl on a foot-powered pole lathe actually worth anyway?

* * *

A Lailey bowl is famous for what it is not. It is not oiled. Not waxed. Not stained. It is never sealed nor sanded. But it is always, always, always made from elm wood, which offers a silver sheen in the afternoon light. You can see one for yourself, along with his tools and his lathe at the Museum of English Rural Life in Reading if you call in advance and book an appointment with a very polite curatorial assistant. This is where Robin Wood, then a forester with the National Trust, first saw one. And nearly 40 years after Lailey’s death, Wood set about teaching himself the lost skill of turning wooden bowls on a foot-powered pole lathe and single-handedly revived the lost craft. “I made my own lathe, copying the Lailey one I saw at the museum. I learned basic blacksmithing so I could forge all my own specialist tools – there was nowhere I could buy them, local blacksmiths were happy to let me watch, and then for about five years it was just trial and error”. At the time Wood was growing all his own food, had two young children and was working full-time as a forester. How did he do it? “I’ve never had a telly”, he says, “that helped”.

* * *

In a typical year around 650, 000 adults pay £20 or so to visit Hampton Court Palace. They go because it’s England’s largest and grandest Tudor structure. They go because they’ve heard about the famous maze, because they’ve grown up hearing stories about Henry VIII and they want to walk, just for a while, in the monarch’s slippers.

“It’s about triggering little moments of time travel”, says Aileen Peirce, creative programming manager of Historic Royal Palaces at Hampton Court Palace. “We see people marvel at the beauty of the buildings, giggle at the tiny details and whisper to their friends about what they think it must have been like 500 years ago”. Peirce says there is an unwritten pact with their visitors. She believes it’s not just about how objects look, it’s about faithfully recreating how they were made, with the right materials, the right methods. And not cutting corners. “Our visitors trust us to get it right, they trust that we will honestly re-create the space as right as we can get it. And a lot of it is down to faithfully filling the rooms with authentically made objects, just as they were”.

So you can imagine how thrilled the Tudor kitchen team was when they found out about Robin Wood and his foot-powered pole lathe turned bowls. After 40 years of not being able to source new bowls or replace existing ones, they could now commission a new set for their authentic cookery demonstrations. If you visit Hampton Court Palace today you will able to see beef roasting on a spit, then dine from bowls just as in King Henry’s day. And as you tuck into your sizzling meat or hearty stew, you will know that the bowl in your hand will have been hand turned, in the 500-year-old tradition, by Robin Wood. If you ask him, he’d probably even tell you exactly which tree it was. But surely, when we talk about heritage crafts, wonderful as they are for castles, their gift shops and people who are into that sort of thing, we are not talking about life and death.

Or are we?

* * *

A cholecystectomy is when your gallbladder has given up the ghost and needs to be taken out. In the 1980s if you needed a cholecystectomy, you would be opened up and the surgeon would use scissor-like instruments that acted essentially as extensions of their hands. If all went well, you would be back to normal in around eight weeks.

If you need a cholecystectomy today, you would most likely have it by keyhole surgery. The incision is a tiny fraction of open surgery and the procedure is conducted via a laparoscope. This is a small tube that has a light source and a camera, which relays images of the inside of the abdomen or pelvis to a television monitor, the instruments behave kind of like remote controls. If all goes well you will be back to normal in around two weeks. If you had a keyhole cholecystectomy in the 1990s and something went awry causing the surgeon to revert to open surgery, this would have been all be in his or her day’s work.

But now, says Roger Kneebone, Professor of surgical education at Imperial College in London: “surgeons coming up as consultants have never done the types of procedures they are doing by keyhole surgery, by open surgery”. In other words: if things go wrong, many surgeons will struggle to get themselves out of trouble. Kneebone worries about the loss of skills in his profession, he sees the brilliant advancement of technology but believes manual dexterity, a feeling for the materials, how human tissue behaves and how it reacts, needs to be preserved. The German philosopher Martin Heidegger calls profound sensitivity to materials “relatedness”. It’s knowing how hard you can pull and how hard you can’t, which things can separate from other things and which things can’t, where you can use sharp scissors and where you can’t. “It’s this relatedness to human tissue that maintains the craft of surgery”, says Kneebone. So what did the professor do when he saw there were the rumblings of a crisis of “relatedness” in his own profession?

He called Stephen Gottlieb. Otherwise known as the man who helped revive the lost skill of lutemaking. The lute was to the 16th century what the iPad is to the 21st. Every educated member of society had one. Perhaps it was also considered rude to toy with your lute at dinner instead of engaging in meaningful conversation with your beloved. But by the late 1700s the lute had all but disappeared. In 1974 Stephen Gottlieb, toured the museums of Europe with the explicit aim of gathering enough information to recreate an authentic baroque lute.

“Stephen, who unfortunately died a couple of years ago, exemplified the sensitivity at the intersection of hands, tools and materials which characterises expert practice in surgery”, says Kneebone. “He gave us a unique insight into how he had developed and revived the forgotten skills of his craft over the course of his career”.

Kneebone chose Gottlieb to talk his students on the Masters in Education in Surgical Education, because in making an instrument, you are making something that has to work, to function, to perform – in many ways not dissimilar from surgery on the human body. Gottlieb taught Kneebone’s students how to experiment with tension, co-ordination and the interplay between different materials, in his case wood and string, and how that could be applied to skin and blood vessels. But the expertise of lutemaking is not the only craft that Kneebone has mined. His Thread Management workshops are bringing together potters, puppeteers and jazz musicians to compare working methods.

“Heritage lacemakers have shown me specific techniques for avoiding thread tangles while sewing around a curved path”, he says, “these are of direct relevance to joining small blood vessels during surgery”.

He calls this process “Reciprocal Illumination”. And it is with this in mind that Kneebone will be anxiously awaiting the Redlist’s initial findings at the end of the year. “Heritage skills are very vulnerable and it will be a tragedy if we lose them. The worst of it is that we may not even know the value of what we have already lost. ”

His principal worry – that future generations of scientists and clinicians will no longer have the hand-eye skills upon which their work ultimately depends.

* * *

The Ise Jingu grand shrine in Mie Prefecture, Japan, is remarkable for many reasons. Set among woodland, the complex includes row upon row of perfectly aligned fencing and includes a magnificent palace of Amaterasu-Omikami, one of the major deities of the Shinto religion. The shrine is also as big as Paris. And every 20 years locals tear it down and then rebuild it from the ground up. They have been doing this for around 1, 300 years. Why? To ensure the craft skills used in every part of the shrine don’t miss a generation and remain in active use. This gives the young apprentices the chance to learn from masters face-to-face, or rather hand-to-hand.

In 2003 UNESCO created an important convention for safeguarding “intangible heritage”. A formal recognition that heritage craft skills, along with oral traditions, performing arts and festive events, are as important as monuments. It came as no surprise that Japan was third of the 168 countries to ratify. There are 198 countries in the world. 30 have not yet ratified, approved or accepted. The UK, along with Somalia and North Korea, is one of them. Patricia Lovett, the vice-chair of the Heritage Craft Association, believes that Japan can teach us a lot about how to treat our makers and how to recognise intangible heritage. “In Britain we are very good at looking after and listing our buildings…but Japan lists its makers as official living treasures. It’s a statement of intent really, showing that it’s the people who create the things and the mastery of the skills that matters. ”

Robin Wood says that while the ratification is “largely symbolic” it would nevertheless declare that “our folk music, cheese rolling and bonfire night is just as much a part of our heritage as Stonehenge.

“Heritage crafts offer many communities a strong sense of identity, ” says Wood, “just think about Stoke potteries and the Sheffield steel and cutlery trade”.

* * *

Wood regularly makes the trip to Sheffield from his home in Edale Derbyshire in the Peak district. He goes armed with his nearly-finished hand-forged axes. The ones he makes to chop the wood for his bowls. He now makes them to sell to the burgeoning numbers of woodturning hobbyists who have been to his workshops, or who have been taught by someone he taught at one of his classes. Wood now thinks there are a good few dozen traditional professional foot-powered woodturners now, and loads of hobbyists “too many to count”.

And as the rolling hills slowly give way to the low rise urban sprawl of Sheffield, you cannot miss the ghosts of the steel industry. They are everywhere. Faded signs. Empty factories. Rust. Boarded windows amid shiny New York-loft-style apartment blocks. We are looking for Beehive Works in the old cutlery area on Milton Street, where Brian Alcock, the last self-employed hand grinder still works, as he has done for 40 years. He is now 72 years old. Robin needs Brian to make the final touch on his axes. Alcock grinds on a millstone machine, as has been tradition for hundreds of years. Local tailors take their knives to be ground by Brian. He says he’ll grind anything. And he gets through a couple of hundred pieces a day. Give or take. Though, he’s just been on holiday, so he’s a bit backed up. He jokes “I might have to skip tea to get Robin’s axes done on time”.

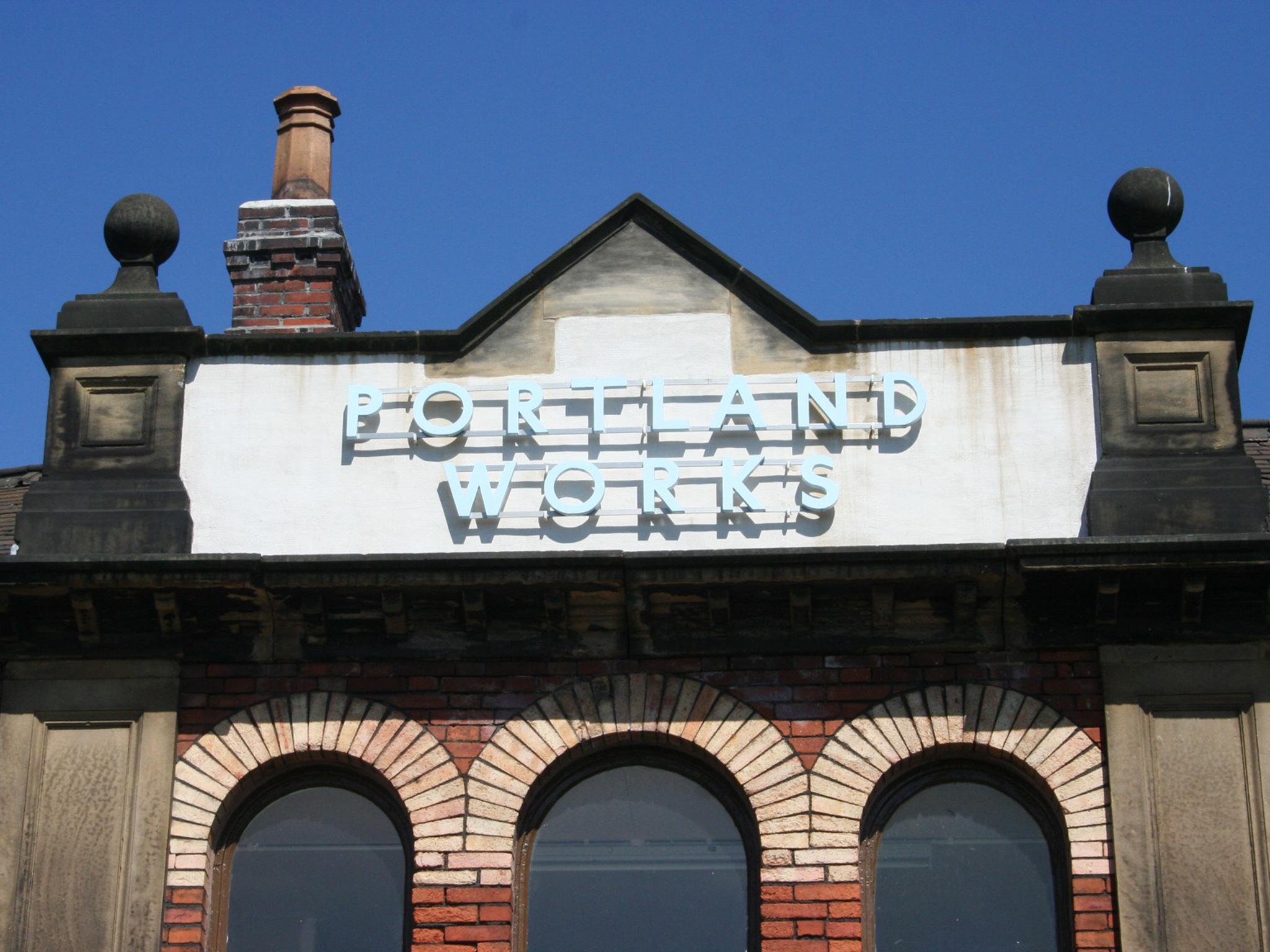

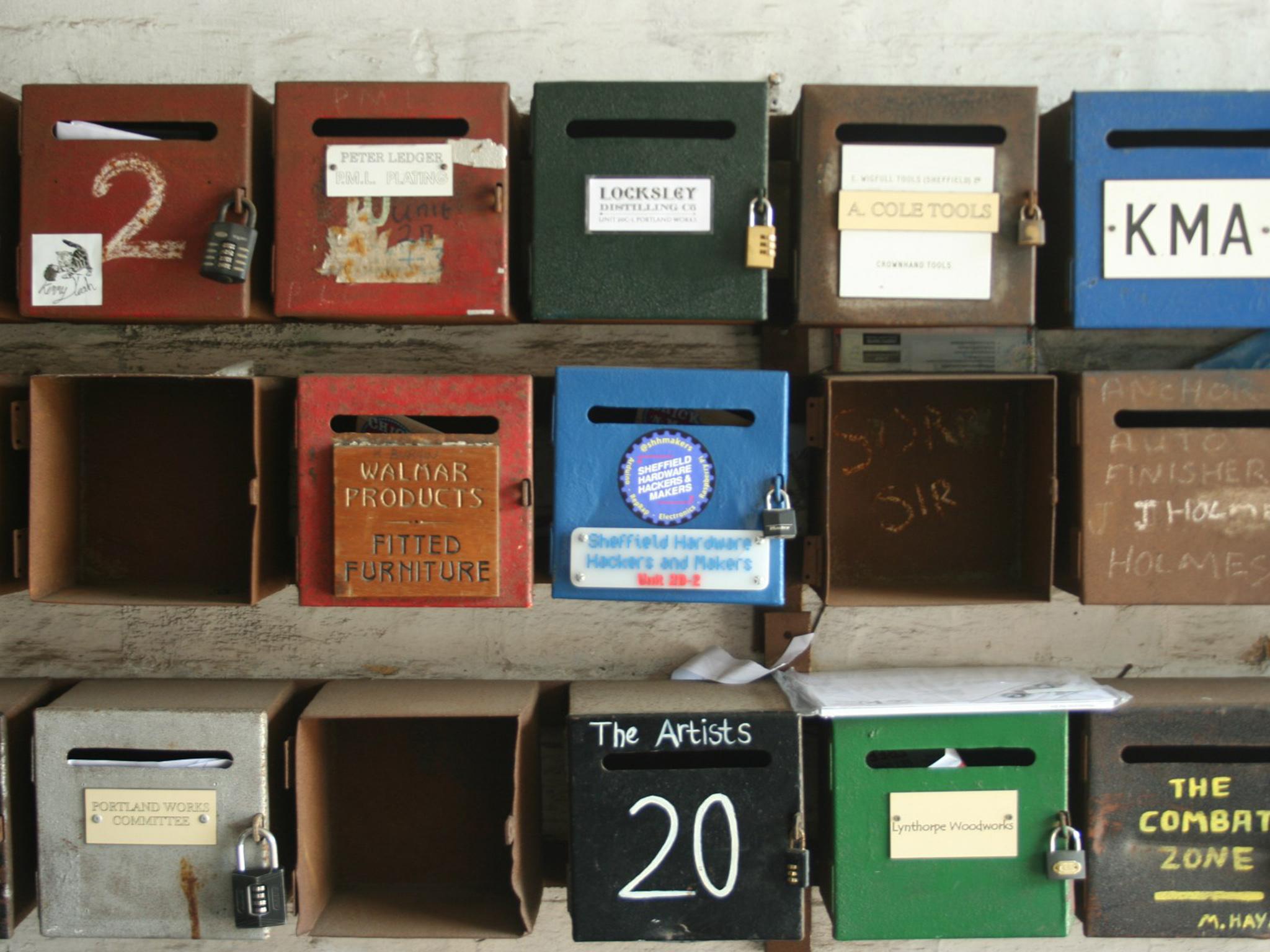

In the 1960s there were hundreds of grinders like Brian Alcock. Now there is just one. His is one name that will certainly feature on the Redlist. A quick drive from Beehive Works is Portland Works on Randall Street. Portland Works is a complex of workshops dating back to 1879. It is often referred to as “the birthplace of stainless steel manufacturing”. It is now the last working example of a purpose-built stainless steel trade workshop.

In 2010, the history of the works nearly came to an end. Not the building. The grade two listed building was never at risk of demolition. But the 29, 000sq ft of workspace was slated to be converted into luxury apartments, all exposed brick, wrought iron, high mezzanine ceilings, that sort of thing. After a public battle, led by Stuart Mitchell, a knifemaker, the Portland Works was saved from conversion and purchased by a social enterprise supported by over 500 dedicated community shareholders. It now houses knife makers and sharpeners; cabinet makers and joiners; jewellers and silver platers; artists; rug and guitar makers; photographers and even a Yorkshire-based gin distillery. And today, Mitchell has some exciting news. A new tenant has just moved in. Michael May, “a young lad”, who has apparently been making pocket knives at a big firm. He’s taken the leap and bought up some of Trevor Ablett’s old tools and equipment. Yes, that Trevor Ablett, the one who passed away at the end of last year. The one who didn’t have an apprentice. The one everyone thought was the last maker of his kind. “I was told of Trevor Ablett’s illness and his wish to sell his equipment. So I phoned him up and got the ball rolling. With all the parts I got from Trevor I decided to carry on with the same traditional Sheffield designs”, May says. And so, today we have learned that the Sheffield handmade pocket knife tradition lives on in Portland Works.

* * *

Back in Robin’s home in Edale, Derbyshire, the pumpkin soup is finished. Crusty bread has mopped up every last drop. The early afternoon sun gives the Peak District’s hills, in every shade of green, a soft almost holy glow. All around Robin’s kitchen is wood. Plates, spoons, dishes. Bowls. And every piece has been made by hand. Just ask, and Robin will tell you about of each one of the objects’ makers. Who they are. Who they were. Where they come from. A vase of spoons is a collection of absent friends. From Norway, Denmark, The United States. One spoon is painted blue. It has tiny stars and is made by one of the best spoon-makers in the world. A young girl, with flaming red dreadlocks and who looks like a Botticelli angel. She is Jojo wood, Robin’s daughter. Jojo is passionate about spoon carving but lately her sights have turned to something else. She’s just taken up an apprenticeship as a clog maker and when the Redlist is released, her name will be beside Jeremy Atkinson’s, the last traditional clog maker in England. In this tiny kitchen in Edale, Derbyshire, a love of heritage craft is being passed down, as it has been for thousands of years, from parent to child.

For more information on the Radcliffe Redlist visit: redlist.Heritagecrafts.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks