Is Julian Assange a political prisoner?

If his real crime is ruffling the feathers of the powerful then the answer is yes ... As he languishes in Belmarsh this Christmas, Mary Dejevsky wonders why a man whose only conviction is breaching bail is being held in a category A prison

Not long before the UK high court ruled that Julian Assange could be extradited to the United States, I was at the Frontline Club in London, where two of his most persuasiveadvocates were explaining his case. About two-thirds of the way through the session, I suddenly realised that I had been here before.

I am not talking about the Frontline, a journalists’ hang-out near Paddington, where I have been many times. It was rather the combination of the bare boards of the top-floor meeting room, the decidedly “alternative” complexion of the audience, and the subdued passion of the speakers as they described a surreal world in which legal process was rarely what it seemed.

Altogether, the occasion reminded me of the gatherings that used to take place in the now defunct Soviet Union in support of political prisoners and dissidents, where the central figure, in this case, Assange, was invariably – and for entirely obvious reasons – absent. Assange, the founder and former editor of the whistle-blowing website WikiLeaks – was then, as now, in prison on the other side of London, awaiting the latest stage in his fight to avoid extradition to the US.

True, there were differences. The session at the Frontline was open and advertised and no one, so far as I am aware, was placing themselves at risk by being there; we only had to go as far as a club room in Paddington, not private flats at the end of Metro lines during those distant Soviet years. And the shelves of shops in the vicinity, unlike their 1980s Soviet counterparts, were full.

Nonetheless, there was the same sense of being out on a limb, the same sense of a beleaguered minority trying to challenge an arbitrary power, and – as the proceedings went on – the same sense of being trapped in a reality where what was legal and illegal had been transposed. It was a world, in other words, not a million miles in spirit to the one those Soviet–era dissidents and their advocates knew only too well.

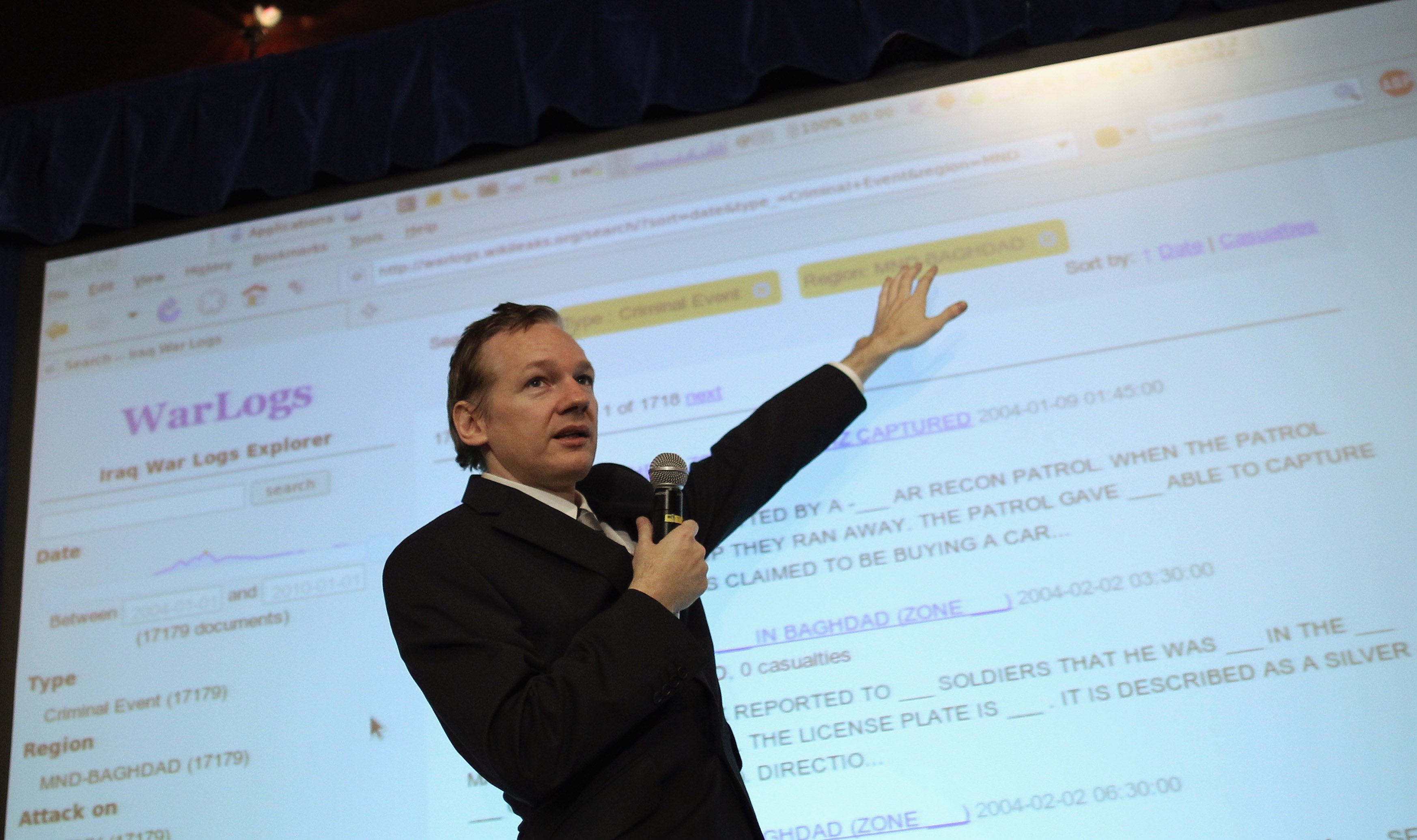

The session was chaired by Vaughan Smith, the founder of the Frontline Club and, in his time, a fearlessly independent war correspondent whose association with Assange goes back more than 10 years. In 2010, Smith had allowed Assange to stay first at the club and then at his country house after Wikileaks first hit the big time with revelations about the killing by US forces of civilians in Iraq and troves of diplomatic documents that had put the noses of many governments seriously out of joint.

Smith had helped put up surety for Assange, when he was bailed pending an appeal against extradition to Sweden on sexual assault charges. By all accounts, Assange could be a difficult guest – and Smith had to forfeit his (lion’s) share of the £300,000 bail money when Assange fled to the Ecuador Embassy 18 months later, breaking his bail.

With Smith on the podium were Stella Moris, Assange’s one-time lawyer, now his fiancee and the mother of two sons, secretly born while Assange was holed up at the Ecuador Embassy, and Rebecca Vincent, director of international campaigning at Reporters Without Borders, a not-for-profit organisation that defends information freedom worldwide. The relatively small number attending, in person and online, illustrated how far Assange, once a popular figure – and a fashionable cause – has become isolated over the years. Smith, Moris and Vincent are among those who have stood by him.

As well as persuasively arguing Assange’s case, including the absurdity of placing a clearly non-violent publisher in Belmarsh – a top security prison more associated with convicted terrorists – Moris dropped a news nugget. She and Assange, she revealed, had requested permission from the prison authorities to marry. In what seemed a gratuitously vindictive response, they had been refused. Lo and behold, the authorities at Belmarsh had a near-instant change of mind. The couple might, by the time you read this, be married.

So that is the context – and time perhaps for an admission. I have not been as enthusiastic in my support of Assange as perhaps I could and should have been. Back in 2010, when WikiLeaks was breaking awkward revelations – awkward, that is, for the powers-that-be on both sides of the Atlantic – he was lionised within the mainstream news outlets that had joined forces to publish the material. He was also embraced by longstanding critics of the establishment, including many activists in the cultural fraternity such Vanessa and Corin Redgrave.

His first big scoop of 2010 fitted well into the anti-Iraq war agenda. It included classified video of a US airstrike in 2007 in which two Reuters journalists had been killed

This was partly because his first big scoop of 2010 fitted well into the anti-Iraq war agenda, as it had been adopted by the hard left. It included classified video of a US airstrike on 12 July 2007, in which two Reuters journalists had been killed – their cameras mistaken for weapons. The same footage showed US troops firing on a van carrying a family that had stopped to pick up the bodies.

This had been followed in July by the release to international media outlets of almost 100,000 documents relating to the war in Afghanistan, including “friendly fire” incidents and the deaths of civilians. Three months later came 400,000 documents from the Iraq war: a flood of information, including confirmation of the use of torture. A month after that, the New York Times, The Guardian and several other European outlets published selected US diplomatic cables – out of hundreds of thousands released on WikiLeaks, which contained profoundly embarrassing observations about international figures and real US policy thinking that had never been intended to see the light of day.

This massive quantity of documents constituted a huge breach of US information security and afforded audiences around the world a rare window on war and diplomacy as they really are, rather than the sanitised and often woefully incomplete version that is all the public usually sees. The US Defense Department said of the Iraq material that it had been “the largest leak of classified documents in its history”.

Still, the enthusiasm for Assange and his work was by no means universal, even among those concerned with free speech. One small factor was that much of the cable material served rather to confirm and lend authenticity to facts that were already known, rather than breaking new ground. Another was the sheer volume: although the published material had been expertly selected and assessed, it was still hard for an outsider to see the wood for the trees.

As he luxuriated in his growing reputation as a bold and visionary trailblazer, there was something offhand and arrogant in his manner that did not sit well with the image of a valiant crusader for truth

But that was not the only reason why this vast journalistic undertaking was more coolly received than perhaps was deserved. Another was the way governments responded to the obviously unwelcome realisation that their secrets were suddenly “out there”, which was to downplay their significance. It was an approach that the UK government had honed to perfection by the time it came to the arguably far more damaging revelations about UK-US intelligence cooperation, leaked by Edward Snowden, from US NSA files three years later.

There was another reason, too. Even some journalists – and I include myself here – had misgivings about such an apparently blanket release of confidential information. How could interstate relations be conducted, if diplomats had to assume their dispatches could become public while the subject-matter was still “live” and in play. The unintended consequence could be not more openness, but more clamming up. “Off-the-record” and “background only” discussions have their uses for reporters, too.

Over and above considerations of information freedom, however, was the character of Julian Assange himself. It was not that his motives were thought suspect: there was no suggestions that he might, say, be working for a hostile power. It was rather that as he luxuriated in his growing reputation as a bold and visionary trailblazer, there was something offhand and arrogant in his manner that did not sit well with the image of a valiant crusader for truth. Added to this were the reports about his behaviour at Vaughan Smith’s home, and the left-wing “luvvies” who surrounded him at the time, who could be as much of a hindrance as a help.

Everything put together made it easy – easier perhaps than it should have been – to dismiss him as a bit of a weirdo, and by extension to undervalue what he was doing. There was also, at that time, no reason to believe that he was under legal or any other threat. He was an Australian citizen and ostensibly safe in the UK. He might have revealed secrets, but they were not UK secrets. There was no law in the UK under which he could have been charged, and if one had been found, there was the trusty old public interest defence that could come to his aid.

Legally, there is also a crucial distinction between someone who divulges secrets they are contractually bound to keep and someone who only receives them and then makes them public. Parallels could be drawn with The Washington Post’s 1971 publication of the Pentagon Papers, which had revealed inconvenient truths about the Vietnam War. The Post was judged to have made public information it had received, not to have stolen the information or incited the leak.

There was also the detail that the headquarters of WikiLeaks was in Sweden. Was this not one of the most solid and reliable countries from which to defend media freedom? Alas, both those assumptions, about the UK and about Sweden, were subsequently to be called into question – which is partly why, 11 years after Assange first strode into the London media scene, I was at the Frontline Club that evening.

Is there not something terribly wrong when an individual whose only conviction is for breaching bail has spent as much time in confinement as some serious criminals?

Leave aside the compassionate grounds of Assange now having a fiancee and two young sons, is there not something terribly wrong when an individual whose only conviction is for breaching bail has spent as much time in confinement as some serious criminals? And if his real crime is ruffling the feathers of the powerful, then is he not, in reality, a political prisoner?

As good luck would have it, those same questions have been posed by someone supremely well qualified to offer answers – and his conclusions should be disturbing to anyone with the slightest interest, professional or otherwise, in legality and free speech – doubly so, now that Assange has lost his latest appeal against extradition to the US.

Nils Melzer is a Swiss lawyer and the UN’s special rapporteur on torture. But don’t let the reference to torture put you off. Some indeed contend that the treatment of Assange amounts to (mental) torture, others may not. That is not the main point here. The point is that, as a lawyer and long-time specialist in international legal systems and human rights, Melzer has applied his expert eye to the fate of Assange and has set out his findings across 300 or so pages in a book due to be published early next year.

The Trial of Julian Assange (Verso, February 2022) has the subtitle: “A Story of Persecution” – from which you will get his drift. But what makes his account even more persuasive than it might otherwise be is that he admits to having started out from the same somewhat sceptical position as I did, and maybe many others.

Explaining the origins of the book, he says that when he was first approached by Assange’s lawyers, in an email headed “Julian Assange is seeking your protection”, he was inclined not to take up the case. “Was this not the founder of WikiLeaks, the shady hacker with the white hair and the leather jacket who was hiding out in an embassy because of rape allegations?” He admits: “Assange? No, I certainly would not be manipulated by this guy. After all, I had more important things to do: I had to take care of ‘real’ torture victims.”

Melzer then turned back to the report he was working on, which was about “overcoming prejudice and self-deception in connection with official corruption”. It was not until a few months later, he says, that he realised “the striking irony of this situation”.

Special rapporteurs, he explains, are appointed directly by the 47 member-states of the UN Human Rights Council and are expected to perform their functions “with the strictest independence”. He works out of the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva, and receives 50 applications for consideration every week. Of these, only a few can be taken up, and even then the rapporteur can only make representation to states and judicial authorities; he has no power to force action, only to recommend.

The bottom line, he says regretfully, is that it is not only in states notorious for their human rights violations where abuse can go unpunished and uncompensated. “When it comes to protecting purportedly ‘essential’ economic and security policy interests, even mature democracies priding themselves on long–standing traditions in the rule of law suddenly start compromising on human rights.”

And in the months that followed, Melzer began to question the assumptions he had, as he puts it, “almost unconciously absorbed over the years” of Assange as “the cowardly rapist refusing to turn himself in to the Swedish authorities. Assange the hacker and spy evading justice in the Ecuadorian embassy. Assange, the ruthless narcissist, traitor and bastard.”

So when, in the spring of 2019, Assange’s lawyers approached Melzer again, he took a closer interest in the documents they had attached. These included more details of the rape case brought in Sweden and a medical report – compiled by a doctor completely outside the Assange camp – that concluded he had been exposed to a host of factors that “were conducive to serious physical and psychological risks, including suicide”.

To cut a long story short, Melzer says he was by now concerned about the “self-righteous ease and and unshakable certainty with which I had accepted a largely unsubstantiated narrative as unquestionable fact”, and decided to “take another look and form my own opinion – based not on hearsay, but on verfied fact”.

What he found makes up the rest of the book. And it adds up to what seems to me the most compelling case yet made for Assange’s defence and a swingeing indictment of politicians, security services and judicial authorities in three countries – Sweden, the US, and the UnK – that customarily regard themselves as paragons of rectitude. Three areas of argument stand out.

The first is Melzer’s detailed investigation into the sexual assault and rape accusations made by two women in Stockholm for which the Swedish authorities sought Assange’s extradition from Britain. Melzer stops short of claiming that Assange was caught in a honeytrap. He does, however, cast serious doubt on the integrity of the legal process – which kept moving the goalposts, for no good reason as he sees it, without serving the interests of the women involved either.

Melzer says he was by now concerned about the ‘self-righteous ease and and unshakable certainty with which I had accepted a largely unsubstantiated narrative as unquestionable fact’

Melzer makes the point that Assange had made himself available to the police before leaving Sweden, but was told he could leave. Only when he was back in the UK was his return sought, which entailed his arrest, brief imprisonment and bail. The Swedish authorities were repeatedly offered the opportunity to come to the UK to question him, but they consistently declined – until one of the charges had run out of time and the other was at a very late stage.

Melzer’s account leaves the impression that the Swedish authorities were deliberately spinning out the proceedings; that it suited Assange’s detractors (not just in Sweden) to have the sex charges – some of the most reputationally damaging allegations that can be made against a man in present times – hanging over him for as long as possible; and that Assange’s reasons for fearing extradition were nowhere near as fanciful as they had been widely presented in the media and as Melzer had once believed.

Which brings us to the US angle. Assange and his lawyers have always argued that it was not facing sex charges in Sweden that he feared, but that Sweden would bow to US pressure to have him sent to face US justice – and not on the relatively trivial charge that the US had initially issued a warrant for, but on full-blown espionage charges. The pretext for this was that he had tried, and failed, to help Chelsea (then Bradley) Manning, the US army intelligence analyst who had delivered the mass of confidential material to WikiLeaks, to break a computer access code.

A widely-held view, initially shared by Melzer, was that Assange was exaggerating the threat of US extradition in order to avoid facing justice in Sweden. In other words, that he was not just an alleged sex offender, but a coward. After considering the iniquities of the US plea-bargaining system and the late addition of 17 charges of spying to Assange’s US charge sheet, Melzer concludes that his early fear of extradition to the US was not only genuine, but entirely justified.

In conclusions that are now additionally pertinent, he found that Assange could face trial in the special espionage court, be held in especially harsh – “special” – prison conditions, and face a jury packed with people sympathetic to the security services.

In view of this, he finds Assange’s behaviour – specifically his flight to the Ecuador embassy – less reprehensible and more understandable than it has often been presented. Melzer also largely absolves Assange from one of the most damaging accusations levelled against him: that the WikiLeaks revelations cost lives. He agrees that Assange made great efforts to ensure that the names of those who might be endangered were redacted, although others handling the information were not so careful.

And finally to the UK. Melzer finds that the UK authorities – for all their preaching about upholding the rule of law – have exploited their supposedly independent legal system to keep Assange in limbo. This, he suggests, could explain the succession of requests and appeals, and the choice of Belmarsh – in the eastern reaches of London – as his place of confinement.

Writing before Assange’s appeal against extradition was rejected, Melzer concludes that, whether Assange ends up before a US court or not, the US will have obtained retribution of a kind as Assange will have lost more than a decade of his life, mired in various legal systems, the latest being the almost labyrinthine judical processes of the UK.

Assange’s supporters, and Melzer seems inclined to agree, believe that these processes have been manipulated against him. You might not think the UK judicial system works like this. But maybe it’s time to think again. It might seem a trivial point in the context of all Assange’s tribulations, but there are other cases where a similar hidden hand might seem to have been at work.

Consider the sexual harassment charges – that resulted in acquittal – against Alex Salmond, the standard-bearer of Scottish nationalism, at a time when the cause of independence was riding high. Was it chance that the accusations were resurrected when they were? Or that Craig Murray – a former diplomat and an awkward customer to be sure, but also a doughty campaigner for media freedom – was sent to prison for contempt of court in the Salmond case. Was that his crime, or was it rather that he had braved dawn queues for access to the court in the Assange case to chronicle proceedings that would never otherwise have seen the light of day?

We shall never know. But the echoes in this country in the here and now of the way political dissent is treated in un-free societies cannot be ignored. The parallels between Assange and those Soviet-era dissidents – the Russian for dissident is “someone who thinks differently” – should be clear. They, like him, were often difficult to deal with, stubborn, driven individuals; but they had to be awkward to pursue their cause. And, as with Assange and Salmond, the authorities were ever alert for any personal weaknesses that could be exploited to undermine their cause.

In their closing message at the Frontline Club, Stella Moris and Rebecca Vincent stressed that what was at stake was not the likeability of Julian Assange. It was about the cause that he stands for: the right of people to know what their governments are up to, even when, or especially when, their governments do not want them to know. Nils Melzer, the UN special rapporteur, reaches the same conclusion, marshalling a wealth of detail and legal evidence to make his case.

In the run-up to Christmas, Assange remains in Belmarsh. His case now returns to Westminster Magistrates’ Court, at a timetable of the court’s choosing, with the odds on his extradition a lot higher. Moris insists they will appeal to the UK Supreme Court but there is no guarantee this will happen, and some fear he could find himself on a plane out of the UK under the cover of a long Christmas holiday.

If, on the other hand, his case were to reach the Supreme Court, it could become a litmus test of judicial independence in this country. At a practical level that might hardly matter. By then, Julian Assange would have been deprived of his freedom for a dozen or more years – a “sentence” longer than many violent criminals have to serve. That is a strange way for any country to uphold the rule of law. Then again, there is no such thing as a political prisoner in the UK, is there? A story of persecution indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments