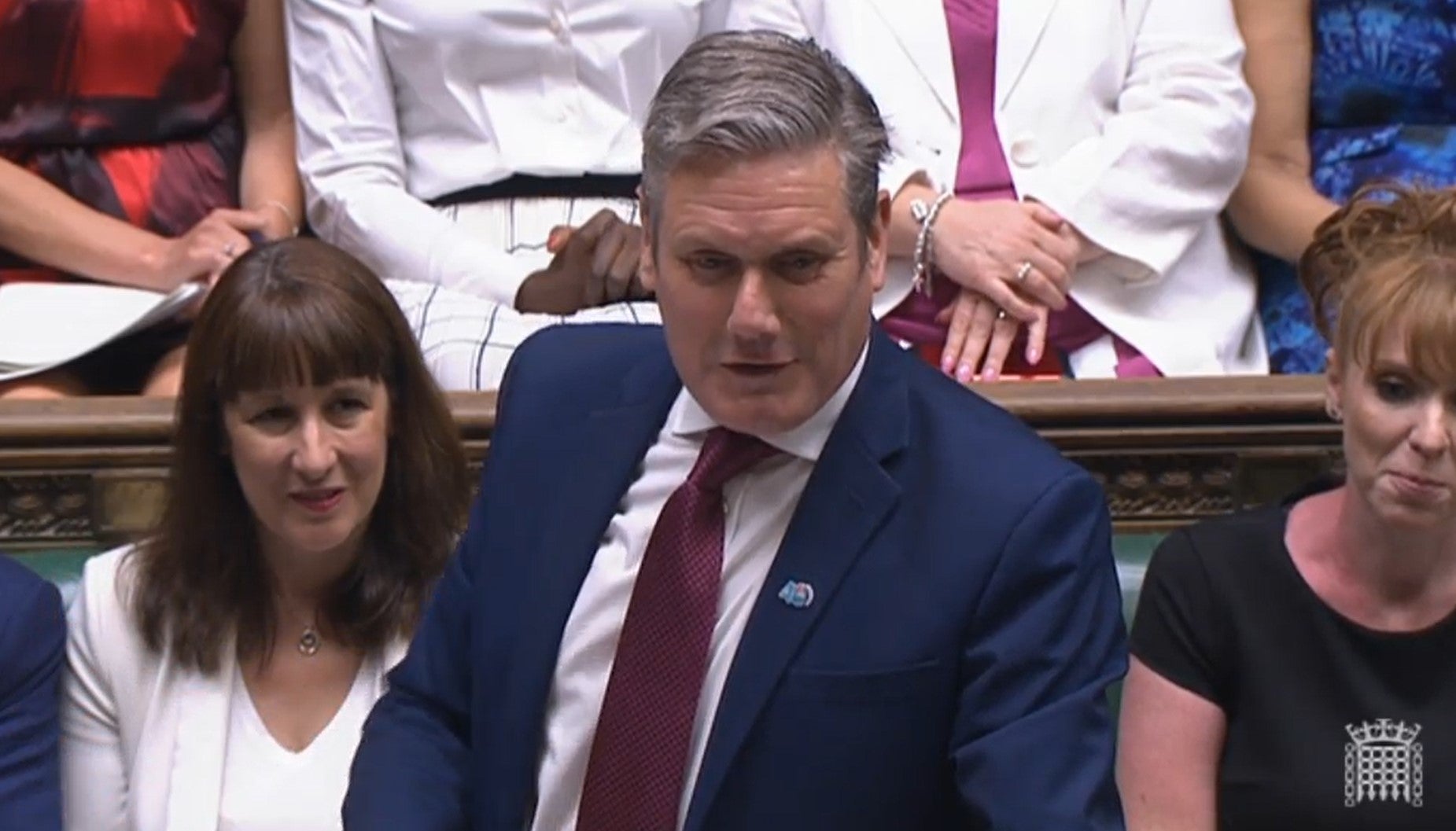

Keir Starmer couldn’t ask the obvious questions of Boris Johnson – so he tried comedy instead

His first effort was not bad, accusing the prime minister of trying ‘Jedi mind tricks’ at Prime Minister’s Questions, writes John Rentoul

Keir Starmer had learned half a lesson from last week’s disastrous outing at Prime Minister’s Questions. Last week he went on too long on the safe subject of the NHS. This week he tried to keep his questions short and started by saying something about himself that was almost interesting.

Responding to Boris Johnson’s tribute to the bravery of the armed forces in the Falklands, the 40th anniversary of which is being marked today, Starmer said that his uncle had served on HMS Antelope, which was sunk in the south Atlantic, and survived.

His first question was simply to ask why the UK is set for lower growth than every major economy, apart from Russia. The prime minister gave a frankly ridiculous answer: “The reason other countries are temporarily moving ahead is that we came out of the pandemic faster than they did.” It made so little sense that Starmer just asked the question again.

At which point Johnson, bored with answering difficult questions, decided to ask his own, inviting Starmer to break his “Sphinx-like silence” on the subject of rail strikes planned for next week.

Starmer was ready for this. He had prepared a “genuinely angry” response, saying: “He’s in government.” But he was cut off by Sir Lindsay Hoyle, the speaker, who disapproves of the prime minister asking questions when he is supposed to be answering them.

This blunted the force of Starmer’s counter-attack, which was: “I don’t want the strikes to go ahead, but he does. He wants the country to grind to a halt so that he can feed off division.”

That could have been a good theme for today’s clash: many people think the government’s policies on the Northern Ireland protocol, and on sending asylum-seekers to Rwanda, are at least partly designed to divide opinion and to energise Conservative supporters.

Starmer could have accused Johnson of wanting to “feed off division” on those subjects as well as on rail strikes – on which the government staged a Commons debate this afternoon, despite saying that the dispute was none of the government’s business and should be resolved by the employers and the unions.

Except the Labour leader didn’t want to talk about any of those subjects, precisely because they are divisive and he is worried that he and his party may be on the wrong side of the dividing line – the opposite side from most of public opinion. Not that most voters have detailed views on Northern Ireland’s post-Brexit trade status, but they don’t want to hear about Brexit again, and many of the voters Starmer is trying to woo are worried that he wants to take us back into the EU.

It was most unfortunate, then, that one of the Labour MPs who had secured a question to the prime minister after Starmer was Anna McMorrin, a shadow minister, who had privately said that a Labour government would “need to renegotiate” the Brexit deal and that she hoped “eventually that we will get back into the single market and customs union, and who knows then”. Predictably, Johnson ignored her actual question, which was about disobliging comments made about him by David Buttress, his new cost-of-living adviser, and said that her private comments were “the real policy of the Labour Party”.

So, no, Starmer didn’t want to ask about Northern Ireland, even if the prime minister is threatening to tear up an international treaty. And he didn’t want to ask about deportations to Rwanda, over which the prime minister is threatening to tear up a different international treaty, namely the European Convention on Human Rights.

Labour cannot be confident that most voters would think that it has a better solution to the problem of small boats crossing the Channel, so Starmer allowed Johnson to get away – in the middle of one of his answers to a completely different question – with the ruthless slur that Labour were on the side of the people-smugglers.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Instead, Starmer tried comedy. His first effort was not bad, accusing the prime minister of trying “Jedi mind tricks”, by waving his hand and suggesting no rules were broken and the economy is booming, only “the Force isn’t with him anymore”.

By now, though, short questions were a distant memory, and Starmer did what he might have done last week, reading out some of the rude things that Conservative MPs said on the record about the prime minister before the confidence vote. It was too long, too late, and the comment that Starmer called his “favourite”, was that Johnson was “the Conservative Corbyn”. Why would he want to bring that up? Why would he want to give Johnson the chance to reply by pointing out that Starmer had tried to make Jeremy Corbyn prime minister?

It was almost as mysterious as the thinking behind a reference to Love Island, which meant nothing to 90 per cent of the MPs in the chamber, including Starmer himself. But most mysterious of all was Starmer’s decision to devote his last question to a long monologue about the economy going backwards.

It was so long that the speaker interrupted and said: “I think we need to get to the end of the question.” But when we did, no one could remember what the question was about, and Johnson was free to talk about all the subjects that Starmer wanted to avoid.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments